Let us pretend that you are asked to perform five consecutive sets of resistance exercise with a one-minute rest between each set. You can choose whatever exercise you like, and you can lift whatever weight you like, but the weight must be the same for all five exercise sets, and you must try to perform as many repetitions as possible during each set. For example, you might choose the biceps curl exercise and a dumbbell weight that allows you to complete 30 repetitions in your first set before failing on your 31st attempt.

My question for you is: after a one-minute rest, how many repetitions do you think you will be able to perform in Set 2? Do you think you will perform more repetitions, fewer repetitions, or do you think your performance will remain the same at 30 repetitions?

If you think your performance will worsen, how many fewer repetitions do you think you will be able complete in Set 2? Do you think your performance will decline by only a repetition or two to 28 or 29 repetitions? Do you think your performance will plummet dramatically in Set 2, and you will complete only four or five repetitions? Or do you think your performance in Set 2 will be somewhere in the middle of those two extremes, perhaps a 50% drop to 15 repetitions?

Then, what do you think will happen to your performances in Sets 3, 4, and 5? If you predicted that your performance in Set 2 will be worse than in Set 1, do you think your performance will continue to drop by the same number of repetitions in successive sets? In other words, what will the trendline of your performance across sets look like?

Scientific insight from personal workouts

Not all scientific insights are inspired by discussions in the presentation halls of academic conferences or on the pages of peer-reviewed academic journals. Some insights come from the events of everyday, non-academic life. Take for example, professor of anatomy, Alf Brodal, who in 1972 had a stroke, and then subsequently detailed his own clinical experiences in a paper published in Brain in 1973. Brodal’s paper has been cited a few hundred times.

In 2021, I also published a paper that was largely based on my personal health experience. In the paper, I argued that the textbook guideline for placing one’s feet on the floor during the bench press exercise is misguided, because it is a historical byproduct of old bench designs and because it causes the spine to assume an unnecessarily biomechanically unsound position. My insight stemmed, in part, from my history with low back discomfort and the relief of that discomfort that I would feel by simply placing my feet on the bench rather than on the floor.

The following story is a second story of scientific insight based on my personal experience.

For a period of about two months in 2023, I was finding it easier and more enjoyable to exercise my chest and arms by doing push-ups at home rather than going to the gym to do the bench press or chest press exercises. My push-up routine was brief and straightforward. It involved completing five sets of push-ups until failure, with a one-minute rest between each set. The total time was about seven minutes, including rest intervals and the time necessary to complete the push-ups. This is an example of resistance exercise “snacking,” which is a type of minimal dose resistance exercise.

To keep myself motivated and accountable, I tracked my performance. I recorded my results in a paper diary.

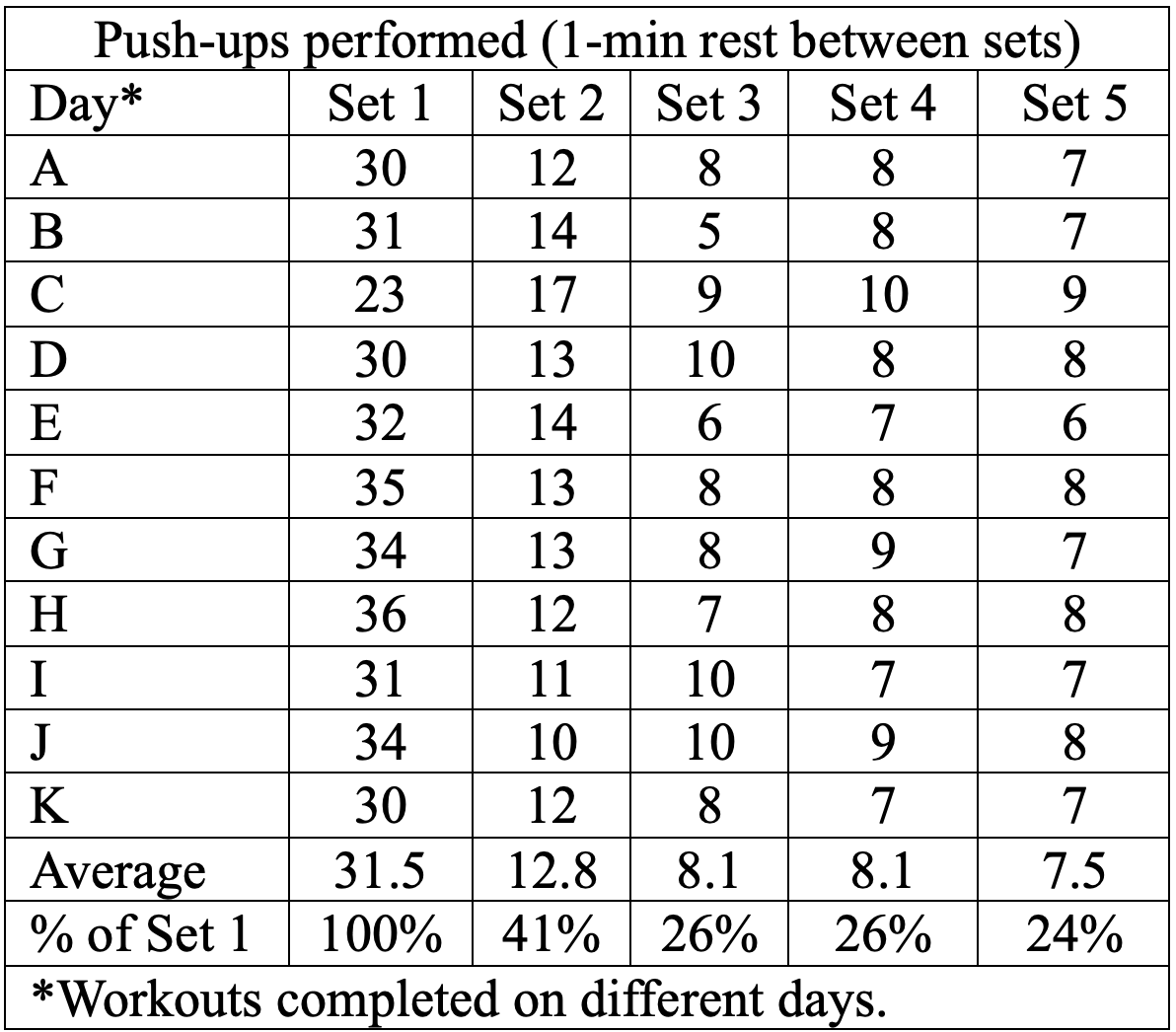

My results are provided in the table below. They show how many push-ups I performed in each of five sets on 11 separate days.

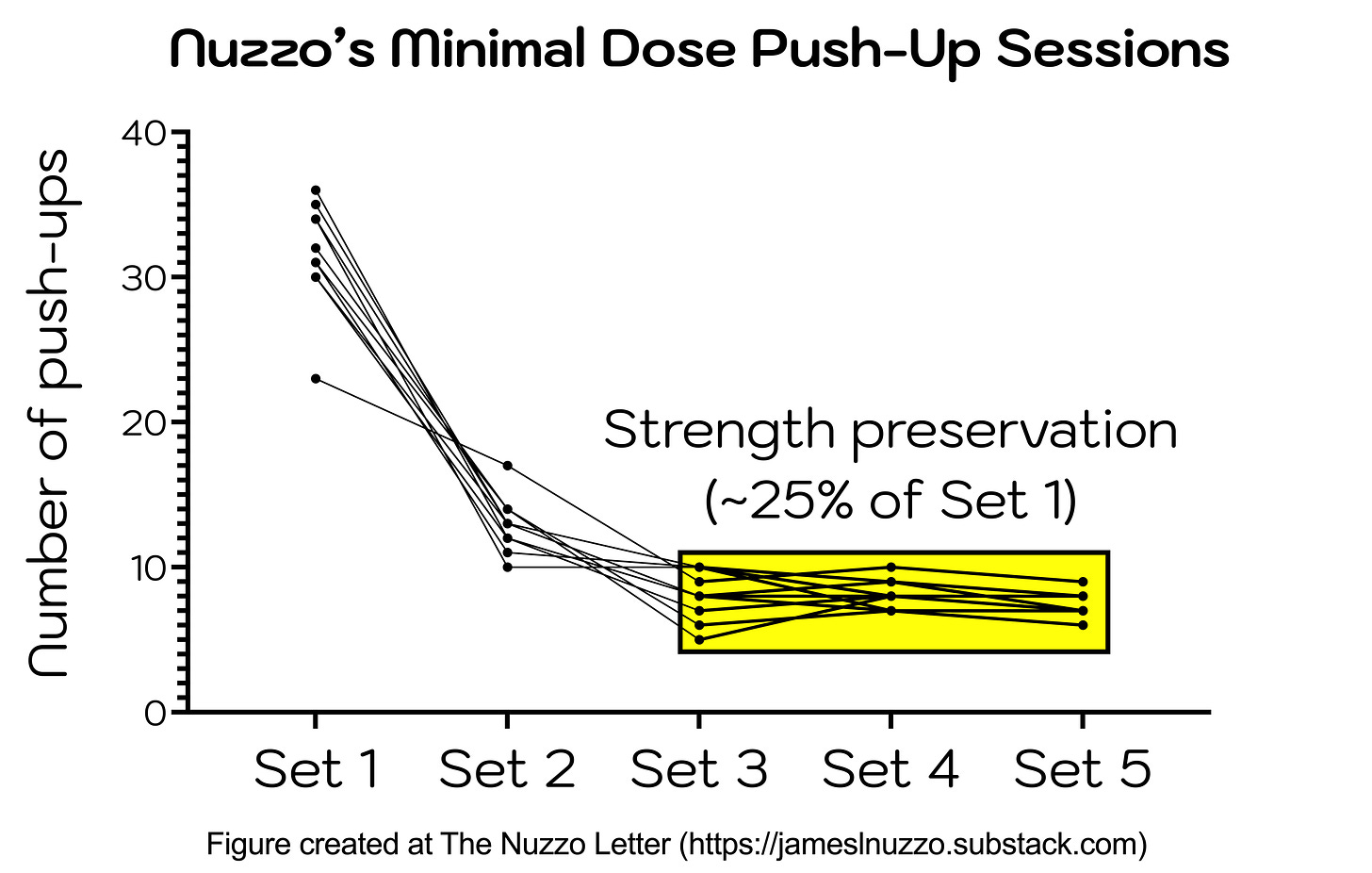

After the first couple of days of performing this minimal dose program, I noticed a fascinating trend in my data. The number of push-ups that I could perform in Sets 3, 4, and 5 remained stable within each session. For example, on the first day, you will see that I performed 8 push-ups in Set 3, 8 push-ups in Set 4, and 7 push-ups in Set 5.

I was surprised when I first saw this trend in my data. I would have predicted that my performance would have progressively worsened as my fatigue accumulated across sets, perhaps to the point of not being able to perform a single push-up by Set 5. However, this was clearly not the case.

And then it hit me. I had seen this trend before.

Muscle fatigue curve

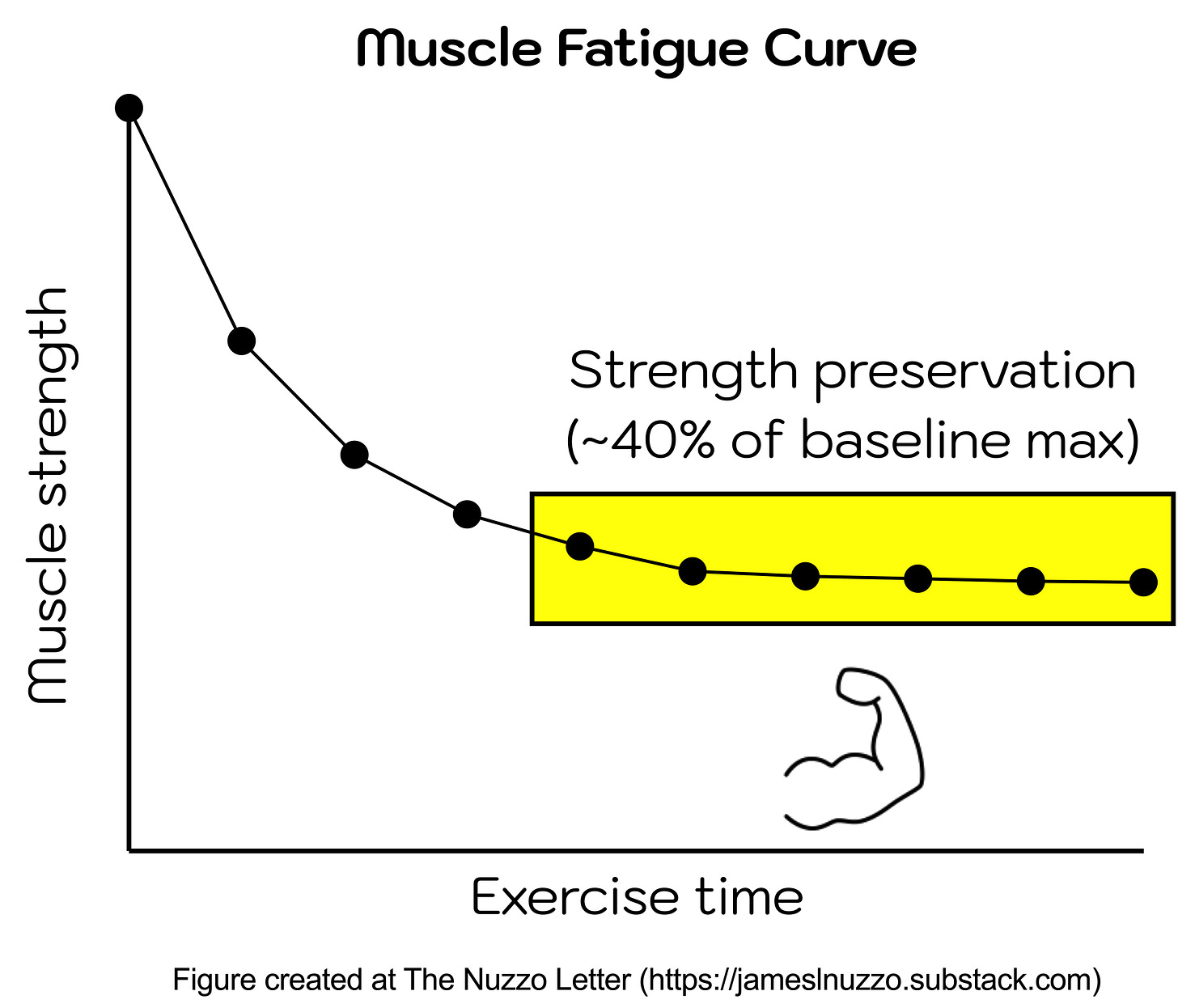

Earlier in 2023, we had published an original research paper and a review paper in the Scandinavian Journal of Medicine and Science in Sports about how muscles fatigue during a type of resistance exercise in which each repetition is performed with momentary maximal force. This can be accomplished using an isokinetic dynamometer in the laboratory or the Vitruvian exercise machine at home. Our original research and our review of 30 other studies revealed that during the first few repetitions of a set of resistance exercise in which every repetition is performed with a momentary maximal resistance, there is a marked decrease in force production in the first few repetitions. This is then followed by a levelling off in force at about 40% of the person’s initial peak strength.

This curvilinear pattern of muscle fatigue, which is depicted in the figure below, is often referred to as the “muscle fatigue curve.” The horizontal tail of the curve has been referred to by various names over the years, including the “fatigue plateau,” “fatigue level,” “endurance level,” and “steady state.” In our review, I used the phrase “muscle strength preservation” because the results suggested that physiological mechanisms within the body allow the body to preserve strength to keep going with exercise and movement.

New research on muscle strength preservation

In previous research, muscle fatigue curves have been documented using either maximal isokinetic or isometric exercise protocols. These tests are common in laboratories but neither of them is the type of resistance exercise that most people do at home or at the gym. Instead, most people select a weight that is a percentage of the maximal weight that they can lift, and they proceed to repeatedly lift that submaximal weight until a high level of fatigue sets in, or in the case of my push-up program, until collapsing to the floor after failing to lift the weight of my own body mass another time.

Thus, in my recent secondary analysis published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, my aim was to examine the possibility of muscle strength preservation during this more common form of resistance exercise. For the paper, I analysed data from 29 studies in which individuals lifted a given weight as many times as they could across four, five, or six exercise sets – similar to my push-up workout. Most studies required individuals to lift a load that was equal to about 70-80% of their maximum.

The results revealed muscle strength preservation, with the tail of the muscle fatigue curve levelling off at about 50% of Set 1 performance. Specifically, the results illustrated that during Set 2, an individual can be expected to complete about 70% of the repetitions that they completed in Set 1. In Set 3-6, an individual can be expected to complete about 45-55% of the repetitions that they completed in Set 1.

However, as expected, the findings also revealed that the magnitude of fatigue that is experienced is impacted by the amount of rest between sets. The shorter the inter-set rest period, the more pronounced the dip in performance. For example, my push-up program included short inter-set rests of one minute, and that is why my performance dipped to 25% of Set 1 before levelling off. Nevertheless, the curvilinear pattern of the muscle fatigue curve occurs irrespective of the amount of rest taken between sets.

Finally, the paper includes a chart where an individual can estimate how many repetitions they can be expected to complete in subsequent sets based on how many repetitions they are able to achieve in Set 1. The chart is intended to be a general guide and educational tool, and it should be used cautiously until more data are available.

Conclusion

We now have evidence from different resistance exercise modalities, that the body is geared up to generate high levels of force for short periods before transitioning to a phase of muscle strength preservation where the body produces lower levels of force for extended periods. This is probably a survival mechanism. Nevertheless, the point of this discussion has not been to iron out all the details of muscle strength preservation and the muscle fatigue curve. Instead, the purpose has been to introduce a fascinating aspect of human physiology. The more one understands how their body works, the more likely they are to value it and take care of it.

Fitness enthusiasts might wonder what the muscle fatigue curve means in terms of designing resistance exercise programs for themselves, for athletes, and for patients. That is certainly a discussion worth having, and I do touch on it briefly in my paper. However, it will need to wait for another day, because right now, I need to hit the floor and crank out five more sets of push-ups.

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Related Posts at The Nuzzo Letter

The muscle fatigue curve