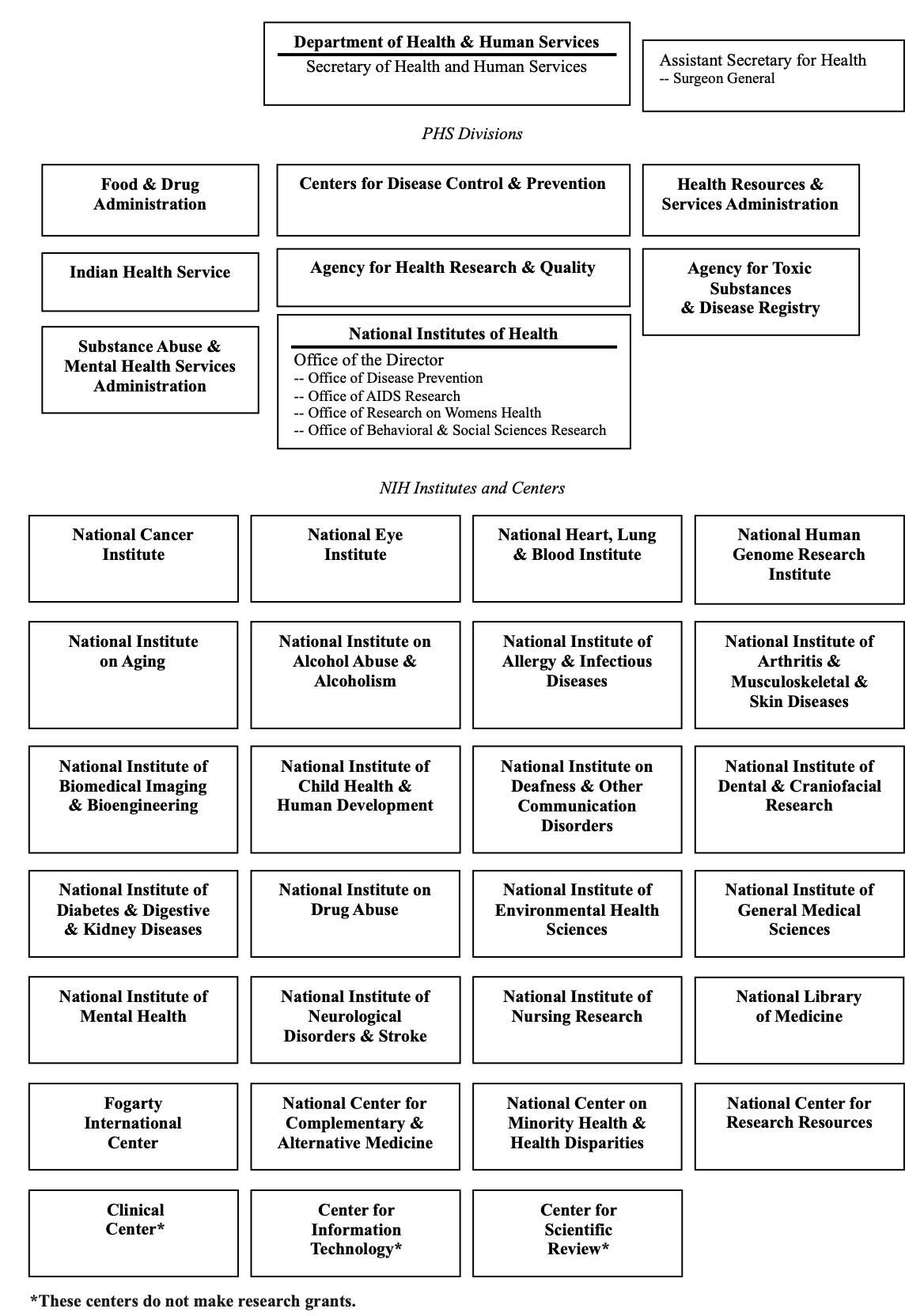

The United States (U.S.) Office of Research on Women’s Health was created within the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 1990. Organizationally, the Office is positioned within the Office of the Director of the NIH. The original goals of the Office of Research on Women’s Health were:

“(1) to strengthen, develop, and increase research into diseases, disorders, and conditions that are unique to, more prevalent among, or more serious in women, or for which there are different risk factors for women than for men;

(2) to ensure that women are appropriately represented in biomedical and biobehavioral research studies, especially clinical trials, that are supported by the NIH; and

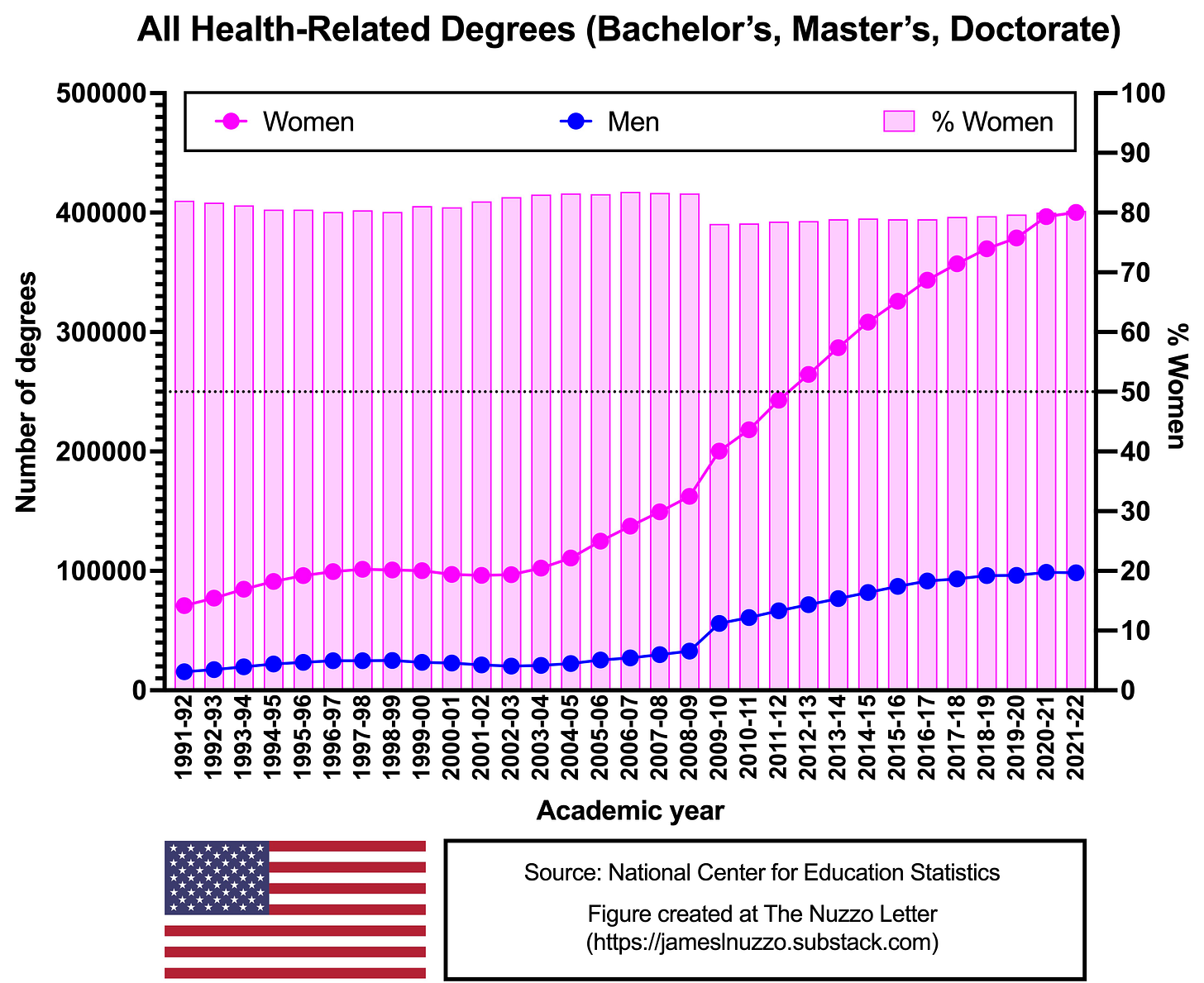

(3) to direct initiatives to increase the number of women in biomedical careers.”

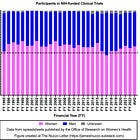

All three goals have been achieved. The goal of increasing the number of female participants in clinical research trials was based on the claim that women were historically excluded from clinical research trials. This claim was largely unsubstantiated at the time that it was made, and numerous studies have since shown that women are not underrepresented as participants in medical research. In fact, reports published by the Office of Research on Women’s Health show that women have comprised 55-60% of participants in NIH-funded trials for the past three decades.

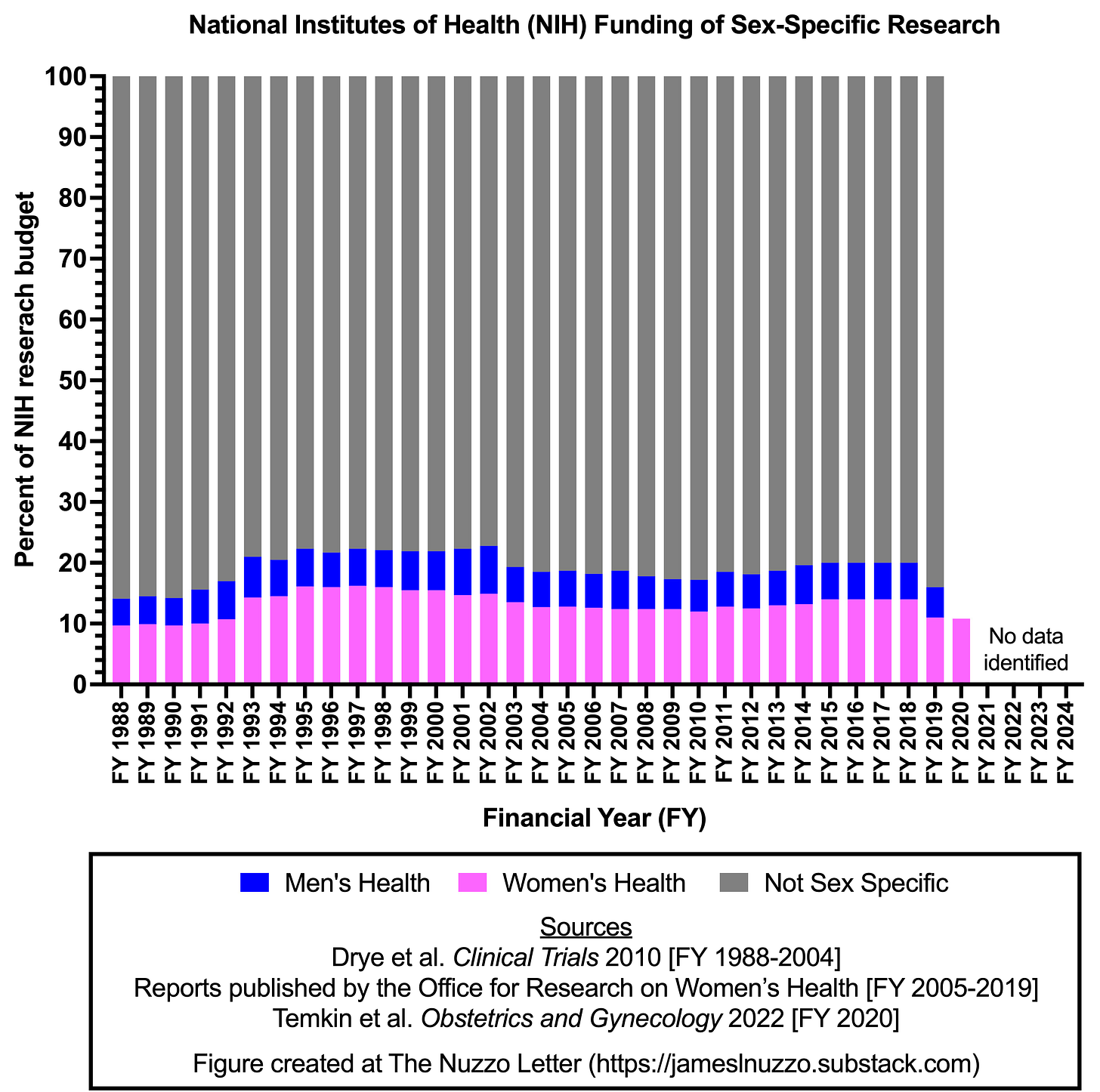

The notion that women have been “underrepresented” in research trials has also been historically linked to the idea that women’s health research has been “underfunded.” This claim is also untrue.

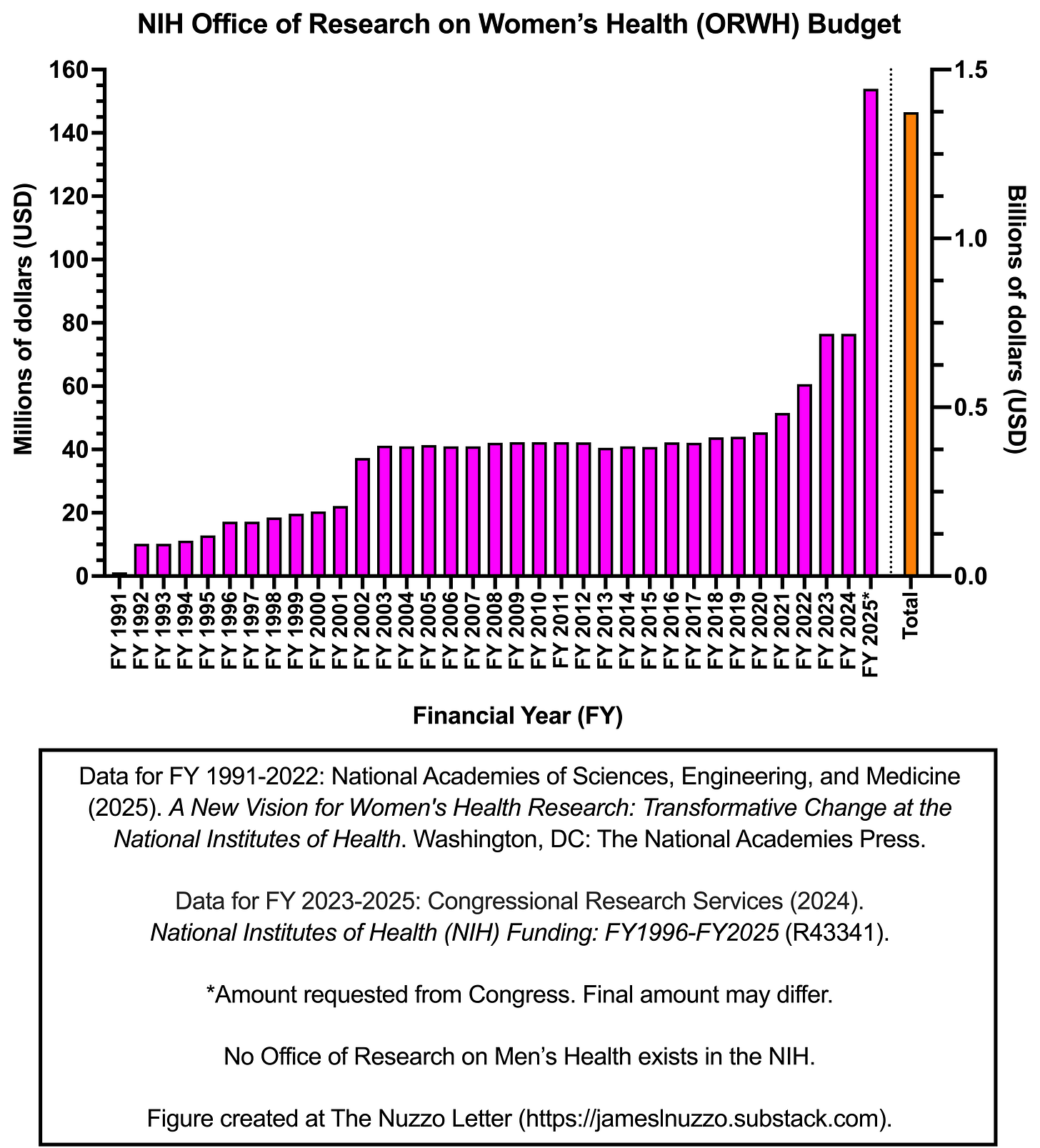

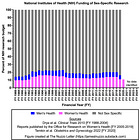

First, as shown in the graph below, the Office of Research on Women’s Health has had its own budget for supporting and coordinating women’s health research since 1991. That budget has totalled approximately $1.3 billion over the past 35 years.

Second, the amount of money that the NIH expends on women’s health research across all its institutes is significantly greater than the amount it expends on men’ health research. As shown in the graph below, approximately 81% of the NIH’s research funding is not sex-specific. However, of the remaining funding that is sex-specific, women’s health receives approximately 13% each year, whereas men’s health receives approximately 6% each year. This amounts to approximately $4.1 billion each year for women’s health research and $1.8 billion per year for men’s health research.

Given the substantial amount of money invested into women’s health research, and the more-than-adequate representation of females as participants in NIH-funded clinical trials, the Office of Research on Women’s Health has presumably also achieved its goal of strengthening, developing, and increasing research into diseases, disorders, and conditions that are unique to or more prevalent among women. If such goals have not been achieved, then taxpayers are owed an explanation for how this could be possible given the billions of dollars that has been invested into women’s health research.

The third goal of the Office of Research on Women’s Health was to increase the number of women in biomedical careers. This goal has long since been achieved. Women comprise the majority of students who graduate from U.S. universities with degrees in health-related fields. Greater numbers of female than male graduates are now observed in many health and medical fields including public health, healthcare administration and management, pharmacy, medicine, dentistry, optometry, physical therapy, occupational therapy, nursing, and psychology. In 2021-22, women comprised 80% of university graduates across all health-related fields.

Given all of this information, one might think that women’s health advocates would want to celebrate the achievements of their original goals. After the celebration finishes, they might even take a moment to consider whether public health attention has gone too far in the female direction, given that male life expectancy is 5.3 years shorter than female life expectancy, and no Office of Research on Men’s Health has ever been created.

As Dr. Warren Farrell says, “When only one sex wins, both sexes lose.”

Unfortunately, no “mission accomplished” celebration seems to have ever occurred, and Dr. Farrell’s conceptualization still does not seem to be understood by many individuals who work within the academic and public health sectors.

National Academies

In December of 2024, the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine – with the input of 17 committee members, two fellows, 10 study staff, eight consultants, and 17 reviewers – published a report titled, “A New Vision for Women's Health Research: Transformative Change at the National Institutes of Health.” The report was also subsequently covered in a piece in Science titled, “NIH needs a new institute for women’s health research, expert panel says.”

The National Academies are not a government agency. According to their website, “The National Academies provide independent, objective advice to inform policy with evidence, spark progress and innovation, and confront challenging issues for the benefit of society.”

From the National Academies’ website, one also learns of their vision, mission, and core values. Their vision is a “nation and a world that rely on scientific evidence to make decisions that benefit humanity.” Their mission is to “provide independent, trustworthy advice and facilitate solutions to complex challenges by mobilizing expertise, practice, and knowledge.” Their core values are “Independence, Objectivity, Rigor, Integrity, Inclusivity, Truth.”

Here, my first aim is to introduce the recommendations made by the National Academies regarding the future of the NIH and women’s health research. My second aim is to highlight the flaws in the National Academies’ report and suggest that these flaws are evidence of the National Academies’ failure to live up to its own professed vision, mission, and core values.

National Academies’ Recommendation #1: NIH Organizational Structure

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should form a new Institute to address the gaps in women’s health research (WHR) and create a new interdisciplinary research fund. Furthermore, NIH leadership should expand its oversight and support for WHR across the Institutes and Centers (ICs). Congress should appropriate additional funding to adequately support these new efforts.”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies further specify that they believe the Office of Research on Women’s Health should be elevated to a position of an independent institute within the NIH and that the Office should be given its own budget of at least $4 billion over the first five years. In addition to this separate budget, the National Academies recommend that Congress establish a new separate fund for women’s health research through the Office of the NIH director. They state that this fund should equal $11.4 billion over the first five years.

National Academies’ Recommendation #2: Oversight and Tracking Investment into Women’s Health Research

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should reform its process for tracking and analyzing its investments in research funding to improve accuracy for reporting to Congress and the public on expenditures on women’s health research (WHR).”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies suggest that the NIH is not currently categorizing women’s health research accurately and that a modified categorization system is necessary to better summarize how much money the NIH expends on women’s health research.

National Academies’ Recommendation #3: Prioritizing Women’s Health Research

“The Director of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) should develop and implement a transparent, biennial process to set priorities for women’s health research (WHR). The process should be data driven and include input from the scientific and practitioner communities and the public. Priorities of the director and the Institutes and Centers (ICs) should respond to the gaps in the evidence base and evolving women’s health needs.”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies also state that most NIH Institutes and Center have plans that “rarely mention women’s health” and that “significant gaps in WHR at NIH are the result of the substantial historical underrepresentation, lack of accountability, inadequate funding, and dearth of comprehensive research that have long characterized this field. Decades of insufficient focus have resulted in critical knowledge deficits and disparities in health outcomes for women.”

National Academies’ Recommendation #4: Careers in Women’s Health Research

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new programs to attract researchers and support career pathways for scientists through all stages of the careers of women’s health researchers.”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies discuss a loan repayment program for researchers who investigate women’s health, expansion of NIH support for early- and mid-career researchers who study women’s health, and additional special considerations for researchers who apply for women’s health research grants.

National Academies’ Recommendation #5: Expanding the Women’s Health Research Workforce

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should augment existing and develop new grant programs specifically designed to promote interdisciplinary science and career development in areas related to women’s health. NIH should prioritize and promote participation of women and investigators from underrepresented communities.”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies discuss expanding the following centers and programs: the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) Program, the Specialized Centers of Research Excellence (SCORE) on Sex Differences, the Women’s Reproductive Health Research (WRHR) program, and the Research Scientist Development Program (RSDP).

National Academies’ Recommendation #6: Women’s Health Expertise on Grant Review Panels

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should continue and strengthen its efforts to ensure balanced representation and appropriate expertise when evaluating grant proposals pertaining to women’s health and sex differences research in the peer review process.”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies want the NIH to ensure that individuals who serve as reviewers of NIH grant applications have adequate expertise in women’s health and that these review panels have “balance representation.”

National Academies’ Recommendation #7: Sex as a Biological Variable

“The National Institutes of Health (NIH) should revise how it supports and implements its sex as a biological variable (SABV) policy to ensure it fulfills the intended goals.”

Under this recommendation, the National Academies further specify that the NIH should expand education around sex as a biological variable and that studies that plan to include sex-segregated data should be given priority in the funding pipeline. Ironically, this recommendation of more research on sex as a biological variable falls within a report that uses phrase like “birthing people,” “assigned at birth,” “girls and gender minorities with uteruses,” and “women and those capable of pregnancy.”

National Academies’ Recommendation #8: Research Topics

Under this recommendation, the National Academies listed a range of basic, clinical, and population-level women’s health research topics that it believes the NIH should prioritize. This list of study topics includes everything from endometriosis, to pregnancy physiology, to menopause, to the “structural and social determinants” of health.

Flawed Plan

The National Academies’ report and its eight recommendations for the future of women’s health at the NIH is flawed for several reasons. The fundamental issue with the plan is that it ignores men’s health. The National Academies did not present epidemiological data on men’s health, nor did the National Academies present data on men’s participation in research trials or on NIH funding of men’s health research. For example, on eight pages in the report, the National Academies say that women’s health has been “underfunded.” Yet, the National Academies did not mention that no office for research men’s health has ever been created, nor did the group present data on funding of men’s health research. Had these presentations been made, readers would have clearly seen that women’s health research has received significantly more NIH funds than has men’s health research. Moreover, on 17 pages in the report, the National Academies say that women’s health has been “understudied.” Yet, the National Academies did not present data on male and female participation in NIH-funded trials. Had these presentations been made, readers would have clearly seen that women have made up 55-60% of participants in NIH-funded research trials since at least 1995. Thus, by not presenting information about men’s health, the National Academies’ report starts from a biased position. Therefore, the report lacks in intellectual integrity.

Damning if True

The National Academies’ report is also problematic in that it is damning if its contents are indeed true. Much of what is revealed in the report implies that the Office of Research on Women’s Health has been entirely incompetent over the past 35 years in completing its mission of supporting and coordinating women’s health research. For example, the National Academies say that we know very little about women’s health and that women’s health has been “understudied” and “underfunded.” How can this be possible with annual women’s health research budgets in the billions of dollars, if not for incompetence? And why should taxpayers then entrust more money and power in the hands of the Office of Research on Women’s Health if this history of underperformance is indeed true?

The reality, of course, is that women’s health has not been “understudied” or “underfunded.” We know many things about women’s health. By suggesting the opposite, and by playing the female victim card to make a political gain, the National Academies unintentionally made the NIH and Office of Research on Women’s Health look foolish and incompetent.

Men’s and Women’s Health Together

One can care about women’s and men’s health simultaneously. The National Academies, via their report, demonstrated that they do not understand this simple humanitarian idea. Instead of choosing to write a report or perhaps two separate reports that included plans for both women’s and men’s health, the National Academies chose to write a report only on the future of women’s health research. In doing this, the National Academies’ failed to demonstrate intellectual rigour and a moral compass, and they failed to live up to the organization’s professed vision, mission, and core values. The National Academies dismissed the sex difference in life expectancy, and it misled readers by not presenting data on men’s health, men’s participation in research trials, and funding of men’s health research. Presentation of this information would have allowed readers to see that women’s health has not been “underfunded” or “understudied” and that the average male in the U.S. dies about five years earlier than the average female.

Instead of arguing only to prioritize women’s health, the National Academies could have simply acknowledged the causes of the sex difference in life expectancy and advocated for increased attention toward specific areas of both women’s health and men’s health.

Instead of arguing for a new single institute for women’s health, the National Academies could have advocated for institutes for both sexes, or it could have advocated for an Institute on Sex-Specific Research that has two branches: one for women’s health and one for men’s health.

Instead of arguing for billions more dollars for women’s health research, the National Academies could have recognized that both men’s and women’s health are important and often intertwined, and therefore, pubic funds ought to be split between men’s and women’s health research.

Instead of arguing only for a larger women’s health workforce and enhanced career development pathways for women’s health researchers, the National Academies could have suggested these things for both the fields of women’s and men’s health research.

Instead of arguing for improved oversight and tracking only for women’s health research, the National Academies could have easily suggested that the same be done for men’s health. In fact, we already know that this problem exists for men’s health research. Biennial reports from the Office of Research on Women’s Health used to include data on both women’s and men’s health research participation and funding, but the Office of Research on Women’s Health ceased this practice in its last report. Moreover, the new NIH Research, Condition, and Disease Categorization (RCDC) system does not list a category for men’s health research and the funding that this category receives, whereas the NIH’s system does list a category for women’s health research and its funding. Thus, we currently have no idea how much money the NIH is investing into male-specific research.

The National Academies chose not to propose any of these things. They chose not to extend their empathy and understanding toward men. For these choices, the National Academies ought to be called out.

Dodged a Bullet

The National Academies report was published in the final months of 2024. The report was likely written with the hope that Democrats would be in charge of the administrative and legislative branches of the U.S. government going into 2025. Democrat power in these two government branches would have facilitated implementation of the National Academies’ plan, as the previous four years of the Biden administration demonstrated a Democrat bias in funding women’s causes. This bias can be seen in multiple graphs published at The Nuzzo Letter. During the Biden years, increased funding can be seen in the budgets of the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Office on Violence Against Women, and the Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. During the Biden years, the NIH also increased its spending on violence against women research, and the Department of Health and Human Services increased its spending on women’s shelters. Moreover, the Biden administration created the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, which allocated another $100 million to women’s health research. Finally, the Biden era was also the time when the Office of Research on Women’s Health stopped publishing men’s health funding data alongside with women’s health funding data – something that the Office had done in all previous biennial reports dating back to 2007.

In other words, those who seek the fair and equal treatment of the sexes dodged a bullet with Democrat losses in the November 2024 elections. Had Kamala Harris won the presidency, and had more Democrats won more seats in Congress, the chances of the National Academies’ grand plan being adopted by the U.S. government would have increased markedly, whereas the Trump administration and the Republicans in Congress are unlikely to adopt the biased plan.

Nevertheless, though the National Academies’ report deserves to be tossed into the dust bin of history for its bias and its lack of genuine humanitarianism, the report should not be forgotten. It will remain dormant, waiting for the next gynocentric administration to come along and implement it. Let us hope that in the meantime, the National Academies see the error of their ways and that they discover a moral compass that points them down an intellectual pathway that involves contemplation of the health of the other half of the American population.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post