[An updated version of this graph has been published at The Nuzzo Letter here.]

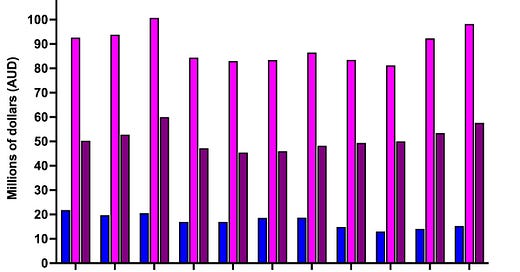

This week’s graph illustrates the money that Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) invests in men’s health, women’s health, and maternal health.

Key Points

Each year, the NHMRC invests about five times more money in women’s than men’s health.

In 2023, the NHMRC invested $98.2 million (AUD) into women’s health and $15.3 into men’s health.

The disproportionate funding does not appear to be due to funding of maternal health, as maternal health is presented by the NHMRC as a separate funding category.

If data from women’s and maternal health are combined into one large women’s health category, the total investment in women’s health is about 10 times higher than in men’s health.

Source: National Health and Medical Research Council. Research Funding Statistics and Data. Updated August 13, 2024.

Bonus Commentary

The NHMRC is Australia’s government agency tasked with funding health and medical research. The data in the graph show that the Australian government invests significantly more money into women’s health than men’s health research. This is odd considering that males in Australia have significantly shorter life expectancies than females. Similar differences in government funding of men’s and women’s health research are also observed in the United States. Thus, data from both Australia and the United States show that women’s health is not “underfunded,” as is sometimes claimed by academics, journalists, and public officials.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you!

That graph is not so obvious when you look at the source.

Thanks for investigating the details.

To what extent, if any, can this be explained by the majority of medical research historically having used only male subjects? Put another way, is this plausibly a catch up effort to address gaps in the literature regarding women's health that are already answered regarding men's health? Are there current disparities in average outcomes for females versus males that this might be attempting to rectify?

This looks really bad, but I don't want to assume that perception is reality without checking for any possible reasonable explanations first.