On September 13th, here on The Nuzzo Letter, I discussed an advertisement for research grants aimed at funding projects in Australia that “address equity issues across the entire higher education student lifecycle.” I explained that the grants were intended to help improve higher education outcomes for six groups. One of the groups was “women in non-traditional areas” while the other groups were based on demographic characteristics that were not gender-specific but that were generally associated with poorer educational outcomes. That men were not considered a cohort of their own in this call for grants was unusual given that in Australia men comprise 43% of university degree earners, and men have earned fewer university degrees than women in Australia for the past two decades. Based on this information, I concluded that the call for grants was evidence of a potential gender bias against men – that is, an inability to recognise male neglect, suffering, or disadvantage.

Here, I want to introduce another possible example of gender bias against men in research funding. In this example, the research funds have already been awarded.

In July of this year, the Australian Research Council – a key funder of university research in Australia – announced some of the projects it would be supporting. One of the projects was titled, “Toward equity in crash protection.” The project was awarded $1 million Australian dollars.

The type of equity being referred to in this project is “gender equity.” This phrase is used almost exclusively to refer to outcomes where women are believed to be behind or neglected and this funded project is not an exception to this trend.

The stated aim of the project is to explore pathways that cause women to be at increased relative risk for death and serious injury from motor vehicle accidents. From the findings, the researchers plan to recommend interventions or policies that can be implemented to “close this gender gap.”

You will note that the researchers referred to relative risk of death and injury from motor vehicle accidents. By relative risk, the researchers are referring to death and injury statistics that have been normalized to some other factor, perhaps number of hours driving a vehicle. Expressing data relative to some other potential confounding factor is legitimate but the surrounding context should always be considered. Here, the surrounding context involves consideration of the absolute number of deaths from motor vehicle accidents and the political nature of the research funding process.

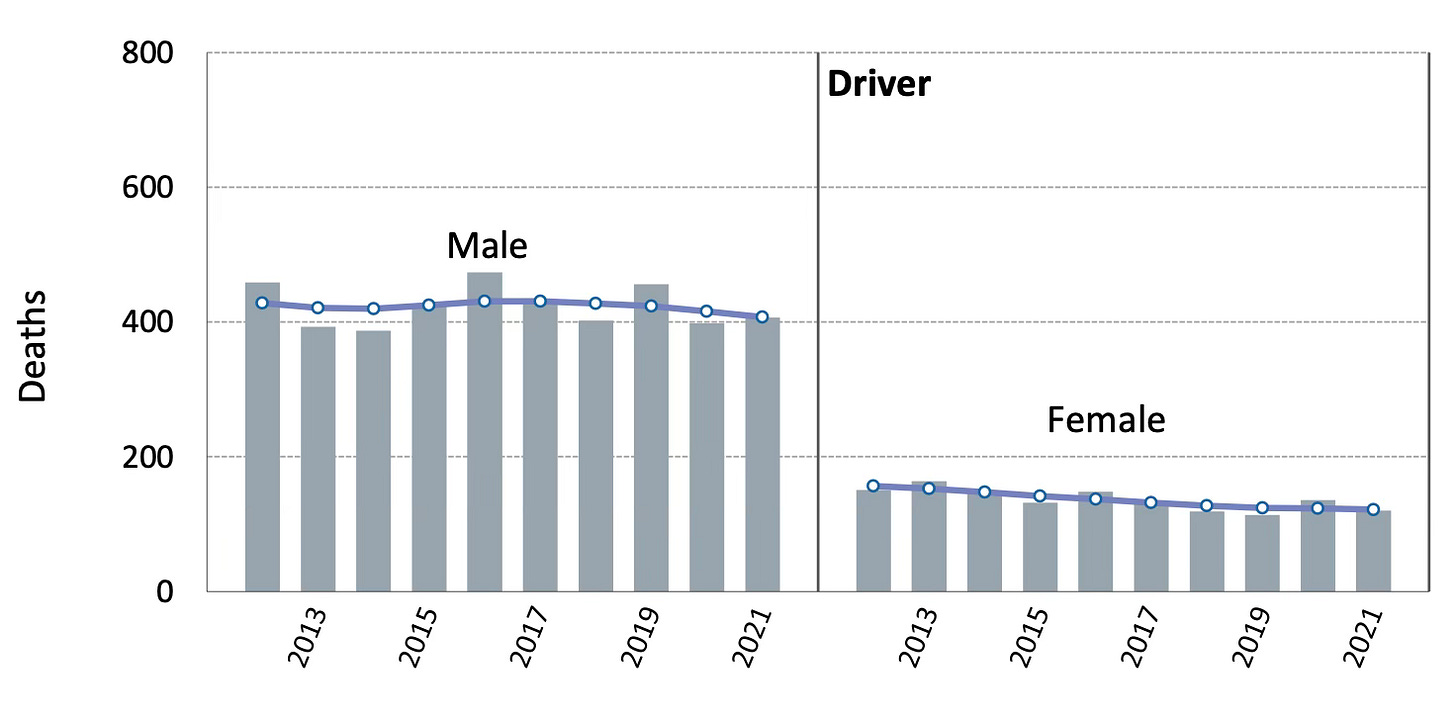

According to the Department of Infrastructure, Transport, Regional Development and Communications, approximately 400 male drivers die each year in Australia in motor vehicle accidents, and that number has remained stable since 2012. For female drivers, the number of annual deaths is about 120 to 150, and that number has gradually decreased since 2012.

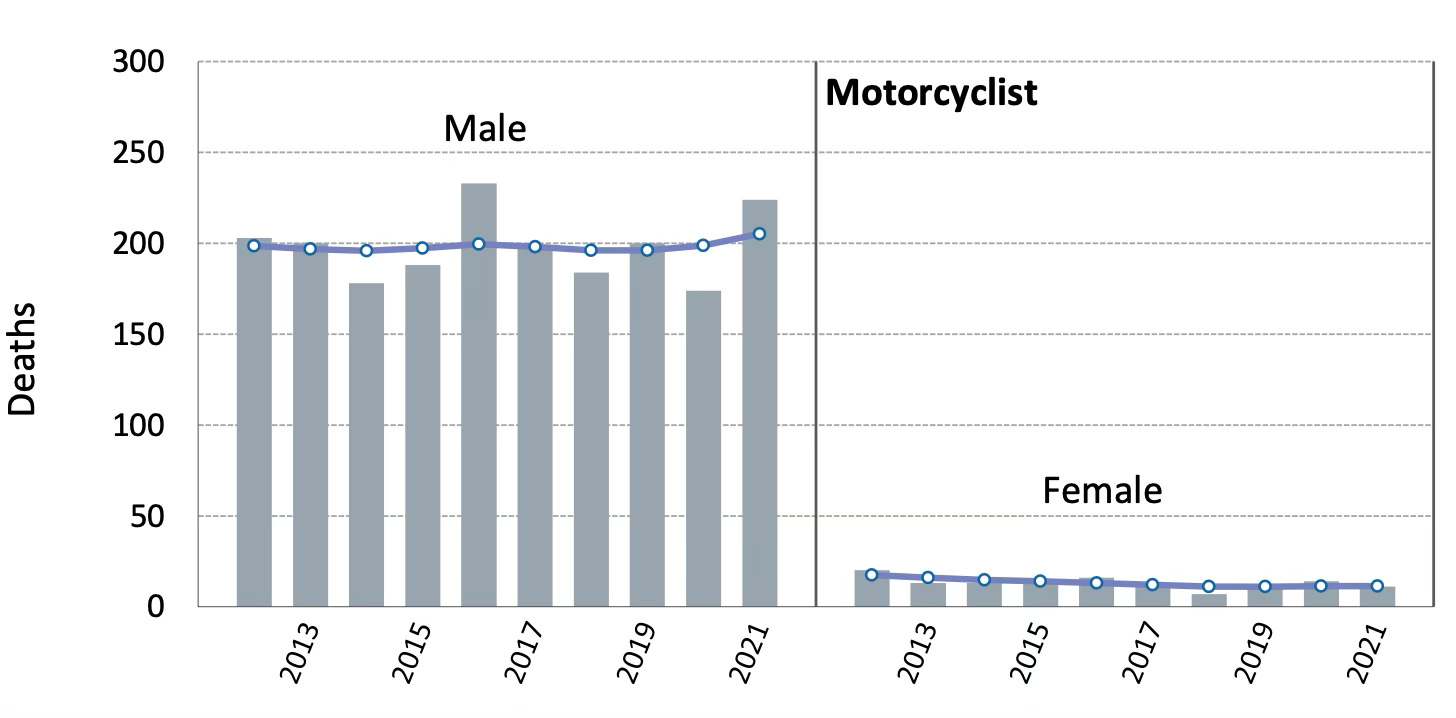

The sex difference in deaths from motorcycle accidents is even greater. Each year, since 2012, approximately 170 to 200 men have been killed driving motorcycles in Australia. The number of women killed each year has been about 10 to 15. Thus, data on absolute numbers of deaths from driving accidents provide an entirely different story about gender equity.

Both relative and absolute risk data are valid ways of reporting study results. Together, they form a complete understanding of injury epidemiology. However, in the case of research into sex differences in motor vehicle accidents, it is unclear why the absolute number of deaths would also not be framed as a “gender inequity” or a “gender gap.” In other words, why does relative risk take precedence over absolute risk, when total body count is perhaps what should be of most concern given the topic at hand?

In my opinion, gender bias and a feminist academic culture, which exacerbates this bias by incentivizing researchers to de-contextualize data to obtain research funds, is the reason that the relative risk data has taken precedence in this research. The way that this research has been framed appears to be an example of what Seager and Barry have called “gamma bias,” which is a type of gender bias in which men’s issues are minimized, while women’s issues are emphasized.

Gamma bias has practical consequences. By minimizing absolute risk, researchers minimize men’s health issues. Also, the factors used to normalize data to be relative risk should not be overlooked, as they can reveal insights into the male experience, including the good that men bring to society. For example, though more motor vehicle deaths among men than women can be attributed, in large part, to particular driving behaviours among men, such as speeding and driving under the influence of alcohol, men also drive longer distances, spend more time driving, and drive more frequently at night. Men are also more likely to drive during inclement weather due to their higher levels of comfort and confidence in driving in such conditions. Thus, though poor decision making contributes to more male than female deaths while driving, men also undertake more of the overall societal workload associated with driving. This includes driving taxis and Ubers, driving big rigs on long hauls, and driving the family on vacations and during blizzards. Moreover, to the extent that a researcher argues that a woman’s increased relative risk for injury is due to cars and their features being designed more for the average male than female body, this, if true, would make sense, given that men spend more time behind the wheel.

In closing, the one million dollars granted by the Australian Research Council on the topic of gender equity in crash protection might help to better understand factors that put women at greater relative risk in motor vehicle accidents. And perhaps this will lead to solutions that reduce this risk. My concern here is that the misguided focus on “gender equity” throughout all of science is leading to the prioritization of female over male flourishment. I am not trying to throw a pity party for men. I am simply trying to highlight potential biases in thinking around the topic of gender and health, which, when practiced repeatedly on a large scale, can have compounding and regrettable effects.

For example, do you remember that at the outset of this presentation I mentioned the research grant that was advertised to improve equity issues in education? Do you remember that this advertisement did not express an explicit concern about male students, but it did express a concern about female students, though women earn more significantly more degrees than men? Well, if academia was more interested in the male experience, perhaps funds could be awarded for programs designed specifically to teach young men about driving knowledge, skills, behaviours, and risks. Sadly, in the current academic climate of gender equity, such programs do not appear to be a priority. This is terribly unfortunate, not just for the young man who might benefit from this education, but also for the first responder, who will need to peel the man’s body from the pavement.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for more evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post