(*Don’t forget to scroll to the end to see more interesting photographs!)

Today, there exists much concern about women’s representation as participants in exercise research. I have covered this topic in essays such as “History Didn’t Start at Title IX,” “Men: The Martyrs of Medicine,” and “Is There a Bias Against Women in Research?”

To the extent that women have been less frequent participants in certain types of research published in specific journals in certain years, this does not then necessitate a conclusion of discrimination against potential female participants. For one, participation in research is not always desired. Some research is boring, confronting, discomforting, invasive, or carries health risks. In fact, our survey revealed that men are generally less worried about such things when contemplating whether to participate in a study.

Discussions about these aspects of research – the tests and interventions administered and how they are viewed by potential participants – are often lacking from papers that espouse gender bias or discrimination as the sole or primary cause of female participant “underrepresentation.” Yet, discussions about the nuisances of research procedures and processes are critical for understanding men’s participation in certain types of research and what their participation has meant for society, including for women. Counterfactuals, or mental simulations, can be useful for facilitating such an understanding.

Consider what would be said today if the historical record were to show that women were 70% of participants in early medical research. Early medical research would have been the riskiest and the most likely to not involve ethics board approval or informed consent. Thus, one can reasonably predict that contemporary gynocentrists would not express glee at this 70% representation, though they should based on their current real-world frustrations about the supposed historical exclusion of women from research. Instead, they would reframe this counterfactual 70% female representation in a way that maintains female disadvantage or victimization. They would state that early researchers, under patriarchal influence, were using women’s bodies for experimentation. In academic papers and books, they would detail this traumatic history and say that these women were brave, heroic, and the martyrs of science.

This mental simulation is intended to highlight an issue with the female underrepresentation narrative and to provoke thought about why we do not extend such considerations to the men who were often participants in the earliest and riskiest research. In part, this lack of consideration might stem from a lack of information available on the history of experimentation, particularly within the fields of exercise science, physical education, physical therapy, and applied physiology.

I recently filled one of these information gaps with a paper published in the Journal of Men’s Health titled “Bibliometric guide to photographs of male participants in early exercise and physical medicine research.”

The purpose of my research was to create a bibliometric list of papers that include photographs of boys and men participating in early exercise science, physical education, physical therapy, and applied physiology research. The list can then serve as a quick reference for educators and researchers who are trying to find photographs to be used in course lectures, university textbooks, and academic papers on the history of research participation. By showing audiences such photographs, educators and researchers can humanize men, showing their contributions to society via participation in early experimental research.

Methods

For the analysis, I searched the entire archives of three of the most historically relevant journals: Research Quarterly (1930-1979), Journal of Applied Physiology (1948-1979), and Medicine and Science in Sports (1969-1979). For these journals, I downloaded their digital archives and opened each individual paper to identify photographs of research participants. I also searched my own personal digital library of articles associated with my previous historical research. My analysis ended in the year 1979, in part, to coincide with my other historical research.

Results

I found a total of 304 papers published before 1980 that included photographs of boys and men participating in early studies on exercise and related topics. Forty-four percent of the papers were published in Research Quarterly. The papers included a total of 733 photographs of 46 boys and 475 men. The earliest paper was authored by Henry Beyer in 1894, and photographs from that paper are shown below.

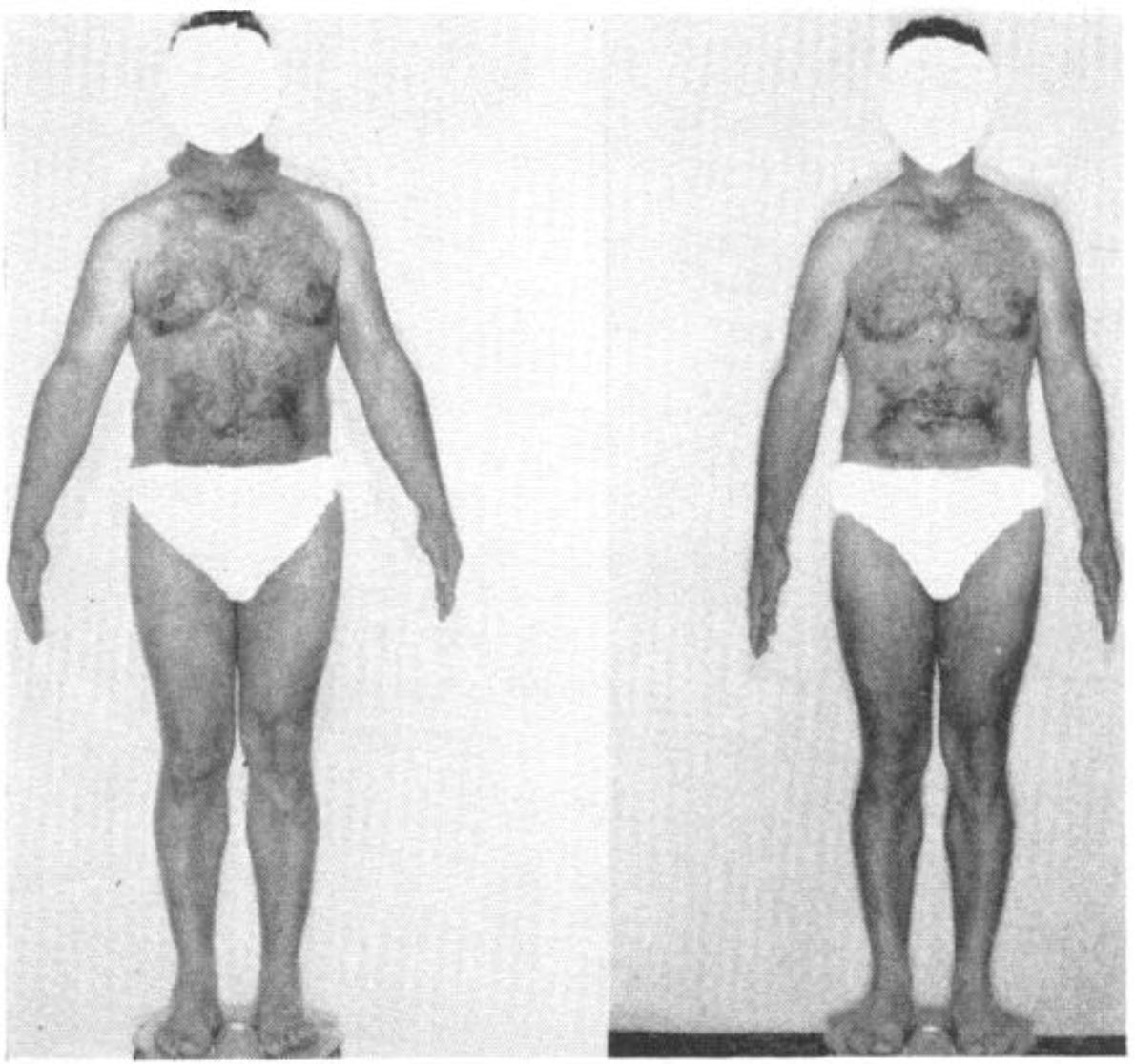

In my paper, I list all 304 papers in tables. The tables include descriptions of the experimental procedures depicted in the photographs and links to where the papers are located online. Often, photographs depicted boys and men performing tests of muscle strength, muscle endurance, and motor learning skills. Men were also frequently photographed having their oxygen consumption measured at rest, during physical exercise, and during exposure to altered environmental conditions. Another common type of photograph was that of male body build and posture. Sometimes, these men were photographed naked.

Many of the procedures that men were shown performing or undergoing are similar to those that women of that era also performed or underwent, including being photographed naked. However, there also appear to be sex differences in the types of procedures completed during this era of science. Examples of such procedures can be found at the end of this post, where I show some of the most intriguing and informative photographs from my research. In my paper, I briefly explain the sex difference:

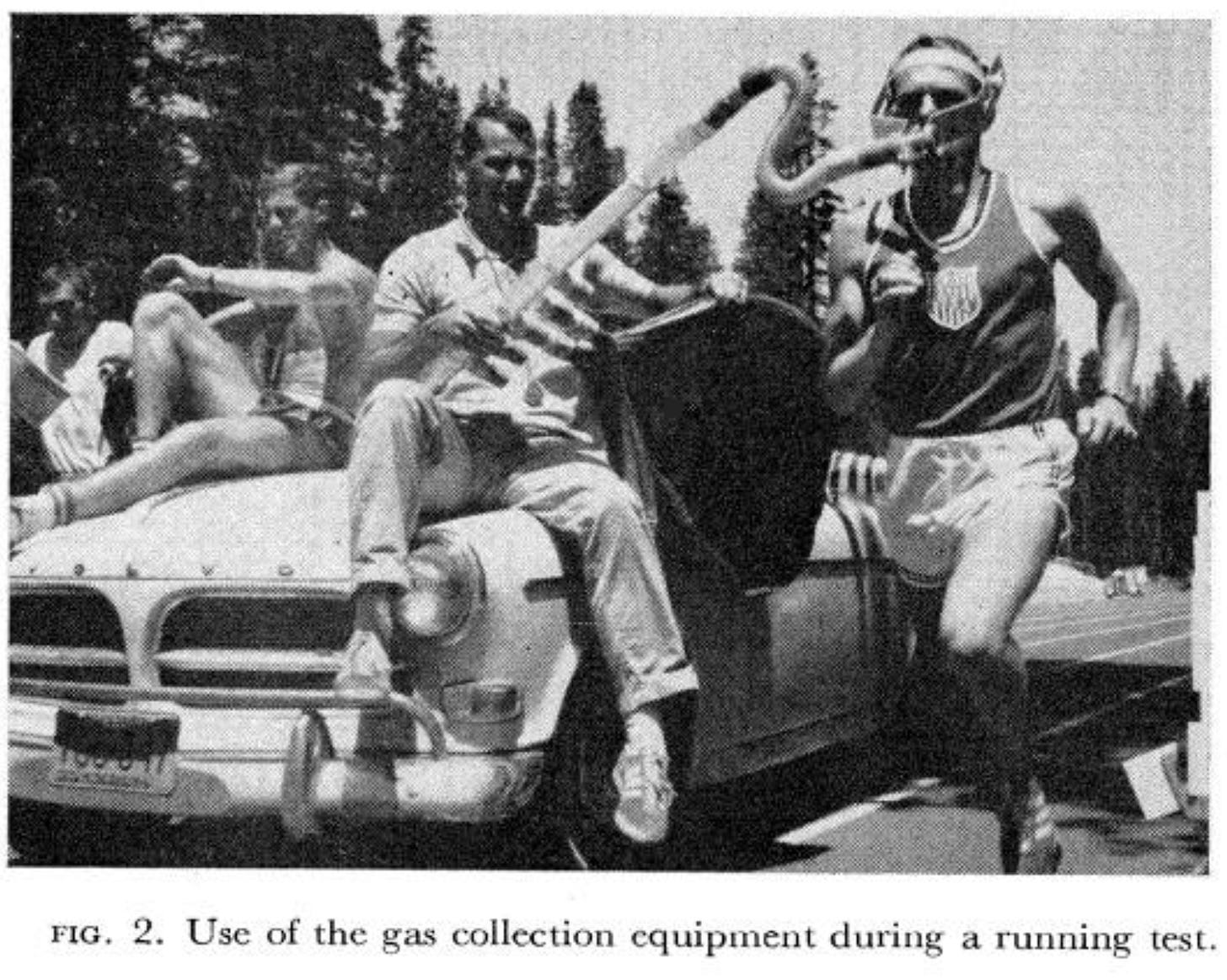

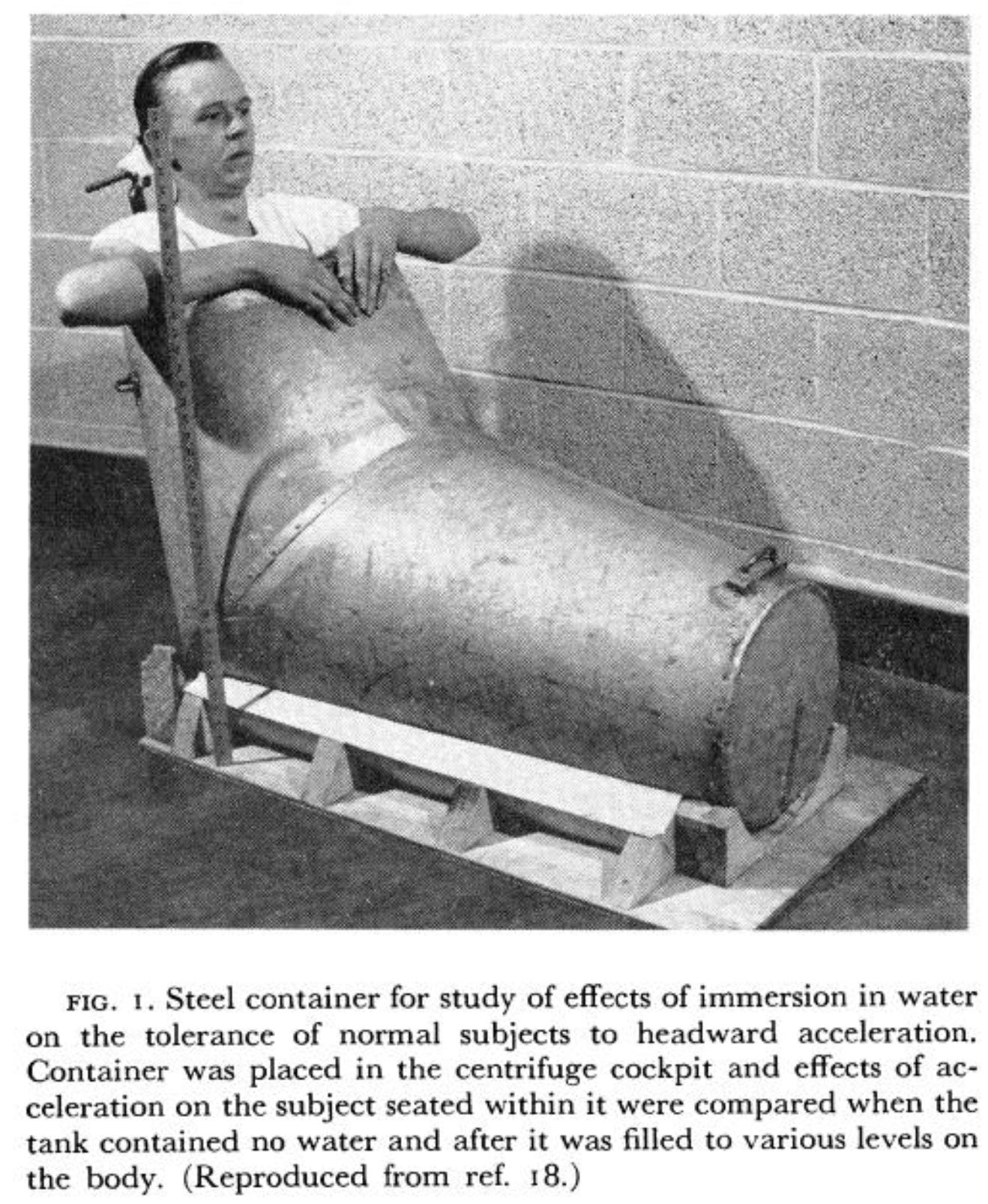

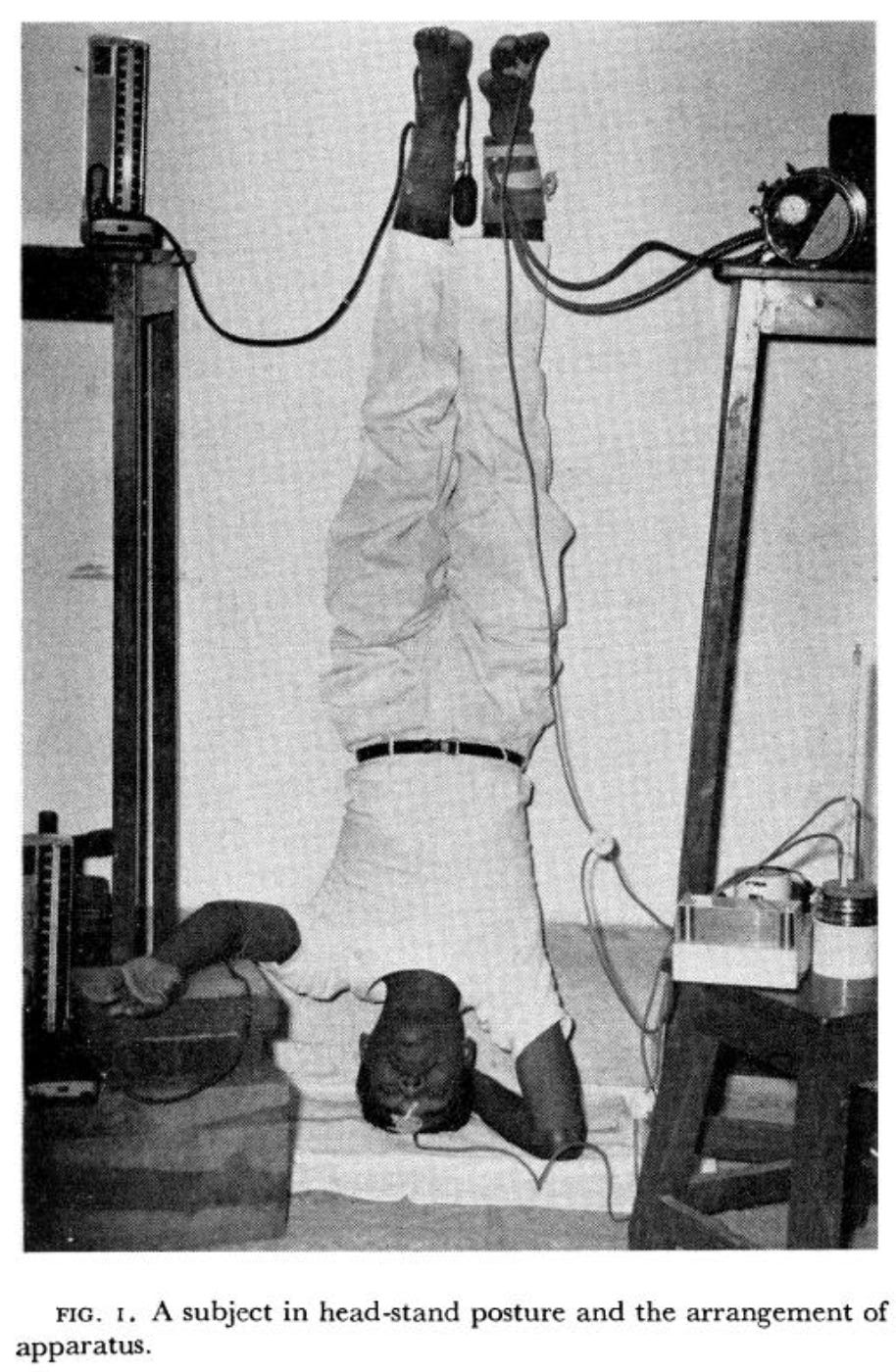

“Photographs in the current bibliometric list illustrate what men’s historical participation in exercise physiology has entailed. These photographs show men participating in a range of physiological and medical procedures. It is difficult to imagine women being more likely than men to volunteer to undergo many of these procedures. Some examples include exposure to high gravitational forces or other environmental conditions that cause “blackouts” or increase the risk of losing consciousness [23, 37, 53, 324]; exposure to gasses that cause itchiness and damage to the skin of the face [87]; sitting on an apparatus designed to induce motion sickness [16]; and standing on one’s head while cardiorespiratory outcomes are measured [31, 35, 65]. In another study, men who were deaf or who had trouble hearing were dumped into a swimming pool to try to better understand human proprioception [172]. Finally, two papers on the bibliometric list include photographs of men sitting on moving cars, while holding gas collection bags, which are attached to a man who is running next to the moving car [79, 94].”

Conclusion

Historical naivety and ideological bias are clouding interpretations of the history of male and female participation in exercise and physical medicine research. My recent paper in the Journal of Men’s Health is intended to help educators, researchers, and students see through these clouds. The discovered photographs show boys and men partaking in a range of experimental procedures, thus providing a basis for educating students about the nature of the type of research that men frequently participated in.

Women also served as participants in much early research. Nevertheless, men completed many experimental procedures that are difficult to envision many women and many other men completing. Thus, the men who did participate in these experiments assumed much of the initial risk of early biological research. Men were often the first exposed to deadly agents, high gravitational forces, or resistance exercise with eccentric overload.

Gynocentrists who write about women’s “historical exclusion” and “underrepresentation” as research participants conveniently ignore such historical nuance. They also fail to recognize that although men might have made up more than 50% of participants in specific types of research in certain years, this does not mean that women’s health and performance were completely ignored. Women were participants in much early research, and claims of their historical widespread exclusion have been debunked multiple times. Moreover, the current narrative of female participant “underrepresentation” is further flawed because it does not acknowledge that sex differences exist in interest and willingness to participate in research. Finally, as illustrated in the counterfactual presented earlier, even if women had been more than 50% of early research participants, contemporary gynocentrists would interpret that as representing female discrimination – in the form of the patriarchy’s use and abuse of the female body. There is simply never any winning against subjective feminist epistemology, which always try to squirm and wiggle its way around objective reality to maintain female victimization.

My hope is that the promoters of the “historical exclusion” and “underrepresentation” narratives take a moment to come off their public soapboxes, which they were likely elevated to by some gender equity initiative, and print off a copy of my recent paper and read it. Then, assuming they have learned something from the paper, they ought to consider taking a figurative knee at the altar of masculinity, and say to the brothers of the barbell and the blackout: “Thank you.”

“Buckle Up, Boys!” Measuring Oxygen Consumption Running Outdoors

Source: Daniels J. Portable respiratory gas collection equipment. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1971; 31: 164–167.

Source: Daniels J, Oldridge N. The effects of alternate exposure to altitude and sea level on world-class middle-distance runners. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 1970; 2: 107–112.

Blackouts and Exposure to High Gravitational Forces

Source: Duane TD, Lewis DH. Electroretinogram in man during blackout. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1956; 9: 105–110.

Source: Wood EH, Lindberg EF, Code CF, Baldes EJ. Effect of partial immersion in water on response of healthy men to headward acceleration. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1963; 18: 1171–1179.

Source: Hoppin FG Jr, York E, Kuhl DE, Hyde RW. Distribution of pulmonary blood flow as affected by transverse (+Gx) acceleration. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1967; 22: 469–474.

“I’ve Got the Scars to Prove It!”

Source: Lambertsen CJ, Idicula J. A new gas lesion syndrome in man, induced by “isobaric gas counterdiffusion.” Journal of Applied Physiology. 1975; 39: 434–443.

Ice Man Plunge

Source: Hall JF Jr, Polte JW, Kelley RL, Edwards J Jr. Skin and extremity cooling of clothed humans in cold water immersion. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1954; 7: 188–195.

Deaf Man Plunge

Padden DA. Ability of deaf swimmers to orient themselves when submerged in water. Research Quarterly. 1959; 30: 214–226.

Back in the Fight: Rehabilitation for World War I Soldiers

McKenzie RT. The treatment of nerve, muscle and joint injuries in soldiers by physical means. American Physical Education Review. 1918; 23: 355–366.

Men at Work

Martin EG. Strength tests in industry. Public Health Reports. 1920; 35: 1895–1926.

Just Hangin’ Around

Gabbard C, Kirby T, Patterson P. Reliability of the straight-arm hang for testing muscular endurance among children 2 to 5. Research Quarterly. 1979; 50: 735–738.

“Nauseous Yet?”: Study on Motion Sickness

Manning GW, Stewart GW. Effect of body position on incidence of motion sickness. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1949; 1: 619–628

“Where Am I?”: Study on Proprioception

Source: Christina RW. The side arm positional test of kinesthetic sense. Research Quarterly. 1967; 38: 177–183.

Boy vs. Polio-induced Strength Loss: Boy Wins

Source: Humphrey T, Rubin D. Comparative strength of neck flexor muscles in normal and postpoliomyelitis children: a preliminary study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1958; 39: 572–576.

Upside Down Science

Source: Rao S. Cardiovascular responses to head-stand posture. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1963; 18: 987–990.

AUM: Oxygen Consumption During Yoga

Source: Miles WR. Oxygen consumption during three yoga-type breathing patterns. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1964; 19: 75–82.

“Ouch!”: Pain Tolerance Testing

Source: Ellison K, Freischlag J. Pain tolerance, arousal, and personality relationships of athletes and nonathletes.Research Quarterly. 1975; 46: 250–255.

“Boys Just Want to Have Fun” and Get Strong

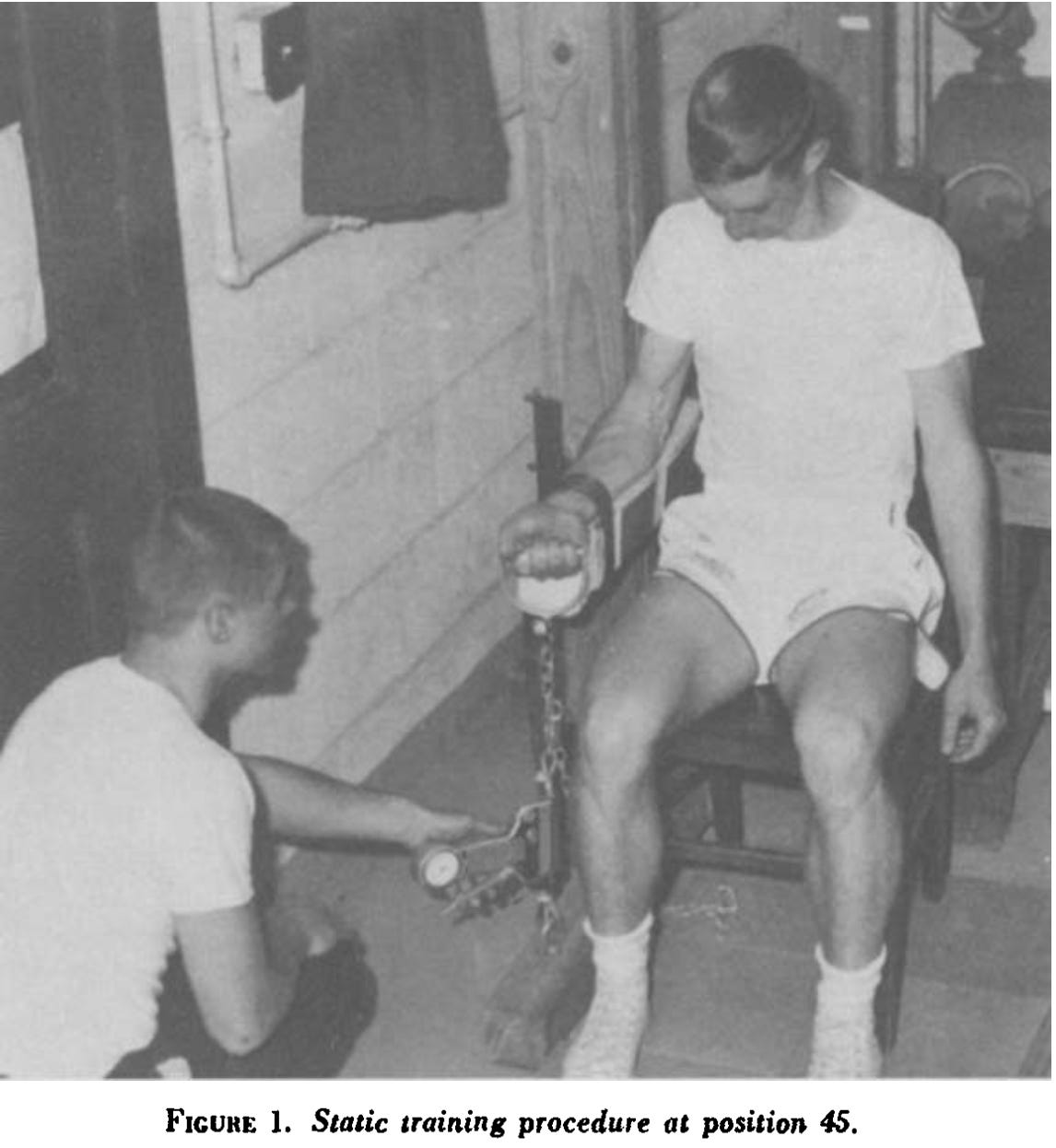

Wolbers CP. Development of strength in high school boys by static muscle contractions. Research Quarterly. 1956; 27: 446–450.

Naked Blokes

Sources:

Carter JE, Phillips WH. Structural changes in exercising middle-aged males during a 2-year period. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1969; 27: 787–794.

Taylor WL, Behnke AR. Anthropometric comparison of muscular and obese men. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1961; 16: 955–959.

Ashton TE, Singh M. Relationship between erectores spinae voltage and back-lift strength for isometric, concentric, and eccentric contractions. Research Quarterly. 1975; 46: 282–286.

Dempsey JA, Reddan W, Balke B, Rankin J. Work capacity determinants and physiologic cost of weight-supported work in obesity. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1966; 21: 1815–1820.

Beast Mode

Gallagher JR, De Lorme TL. The use of the technique of progressive- resistance exercise in adolescence. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery. 1949; 31: 847–858.

Belka DE. Comparison of dynamic, static, and combination training on dominant wrist flexor muscles. Research Quarterly. 1968; 39: 244–250.

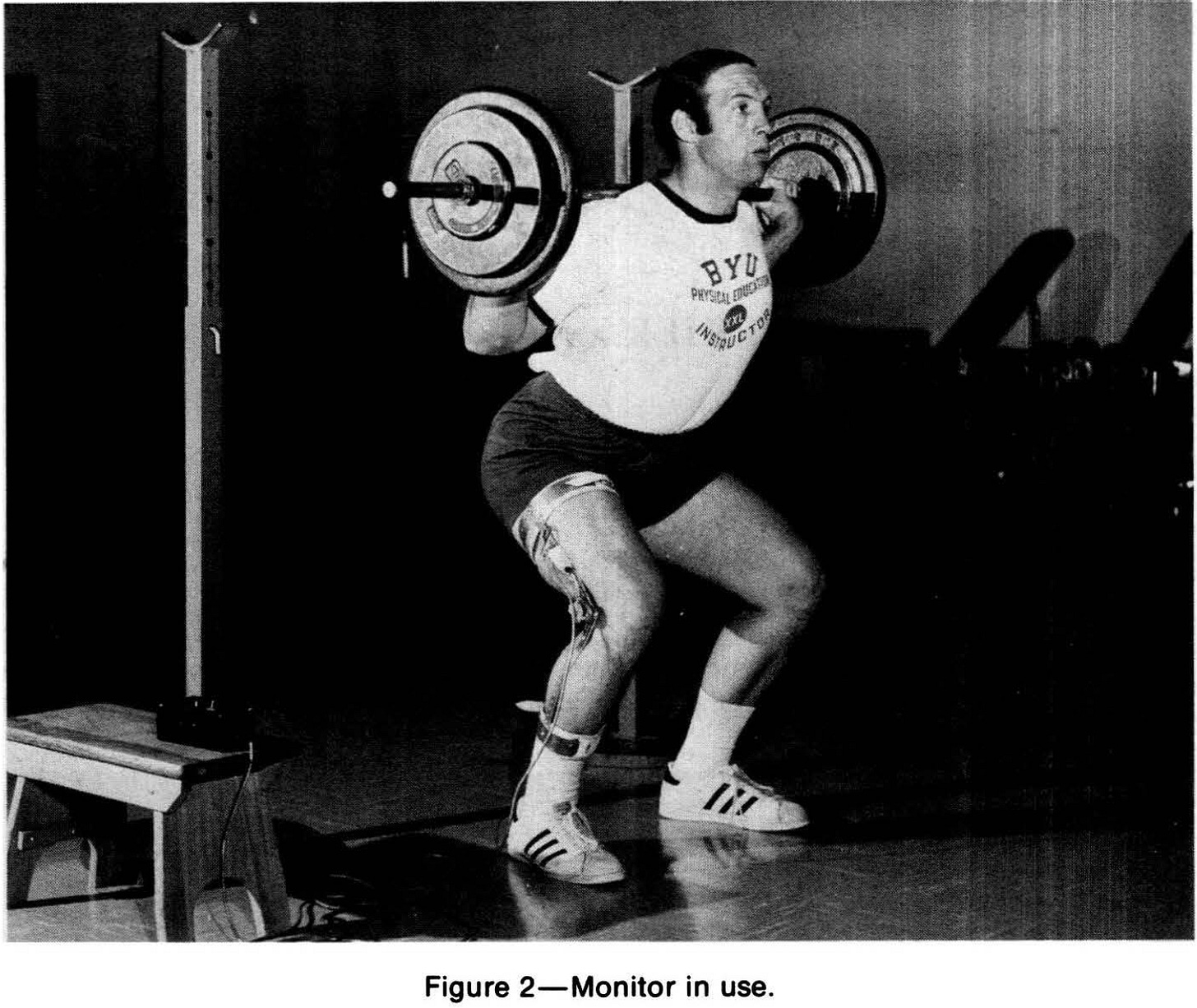

Fisher AG, Ramey JS. Electronic squat monitor. Research Quarterly. 1977; 48: 213–216.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post