Supreme Misrepresentation

Amicus Brief Submitted to U.S. Supreme Court Distorts My Research on Childhood Sex Differences in Muscle Strength

In November 2025, amicus briefs were submitted to the United States (U.S.) Supreme Court in Little v. Hecox. According to the Alliance Defending Freedom, “[t]he American Civil Liberties Union is challenging Idaho’s Fairness in Women’s Sports Act to force female athletes to compete against biological males who identify as female.”

One of the amicus briefs was co-authored by Joanna Harper - an adjunct professor at the International Centre for Olympic Studies at Western University in Canada; Philip Chilibeck - a professor of Kinesiology at the University Saskatchewan and past president of the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology; and Carol Ewing - a professor of Kinesiology and Movement Sciences and Education at Columbia University Teachers College.

In the brief, Harper and colleagues are described as “world-renowned researchers,” who are “interested in ensuring the record in these cases reflects the scientific consensus on the core questions of whether boys have an athletic advantage over girls before puberty…” Also, Harper is a male who identifies as a woman.

On page 9 of the brief, Harper and colleagues included a paragraph and a footnote about two of my peer-reviewed meta-analyses on childhood sex differences in muscle strength. One of my meta-analyses, which I call here Meta-Analysis 1, quantified the size of the sex difference in grip strength at each year of development from birth until age 16. My other meta-analysis, which I call here Meta-Analysis 2, quantified the size of the sex difference in muscle strength of various lower-limb and upper-limb muscles (other than grip strength) in children and adolescents between 5 and 16 years old.

My aim here is to present Harper and colleagues’ comments and then explain how their comments misrepresented my research.

Harper and colleagues’ comments on my research in their amicus brief:

“The Professors also refer to two papers published this year regarding hand-grip strength and upper and lower limb strength, suggesting that the papers show biologically based differences. (Profs.’ Br. at 15-16) (citing James Nuzzo, Sex Differences in Grip Strength from Birth to Age 16: A Meta-Analysis, 25 Eur. J. Sports Sci. e12268 (2025); James Nuzzo & Matheus D. Pinto, Sex Differences in Upper- and Lower-Limb Muscle Strength in Children and Adolescents: A Meta-Analysis, 25 Eur. J. Sports Sci. e12282 (2025)). But as the authors of these studies make clear, “the current research does not reveal the cause of the sex difference in grip strength in children and adolescents.” Nuzzo, Sex Differences in Grip Strength, 25 Eur. J. Sports Sci. at 12 (2025).7 In addition, it is considered within the range of normal for male puberty to begin at nine years old, and these papers include individuals nine and older. Because individuals who have undergone male puberty were included, these studies cannot be used to discuss athletic performance before puberty. Finally, these papers discuss discrete physical capacities, which do not necessarily equate with athletic advantage. For example, several studies in the exercise science field have determined that hand grip strength is a poor indicator of overall athletic ability.8”

Footnote from Harper and colleagues that accompanied the above paragraph:

“7 Lastly, these papers are meta-analyses that were not conducted according to proper scientific methods for meta-analyses. Meta-analyses depend on the papers included in the analysis, and there are well-established guidelines meta-analyses must follow to be considered rigorous and replicable. In both articles, however, the authors acknowledge that they did not follow these guidelines, and that as a result their findings are likely not reproducible. Specifically, the studies the authors included in their analysis, and the method they used to select them, is not transparent; as a result, other scholars cannot reproduce their search. See Nuzzo, Sex Differences in Grip Strength, 25 Eur. J. Sports Sci. at 12 (“[The study] did not explicitly follow PRISMA guidelines . . . [the literature search] did not follow a formal flow diagram. Thus, replication of the search will be difficult.”); Nuzzo & Pinto, Sex Differences in Upper- and Lower-Limb Muscle Strength, 25 Eur. J. Sports Sci. at 8 (“The current study has limitations. First, the literature search did not follow a formal flow diagram. Consequently, replication of the search is probably not possible.”). This method is improper because it can lead to a biased study sample while obscuring its bias. Because of this core deficiency, both studies should be rejected.”

Nuzzo’s response to the above comments from Harper and colleagues:

The claims made about my research by Harper and colleagues are misguided for a few reasons.

1. Harper and colleagues stated (a) “it is considered within the range of normal for male puberty to begin at nine years old,” (b) that my two meta-analyses included “individuals nine and older,” and (c) that “[b]ecause individuals who have undergone male puberty were included, these studies cannot be used to discuss athletic performance before puberty.”

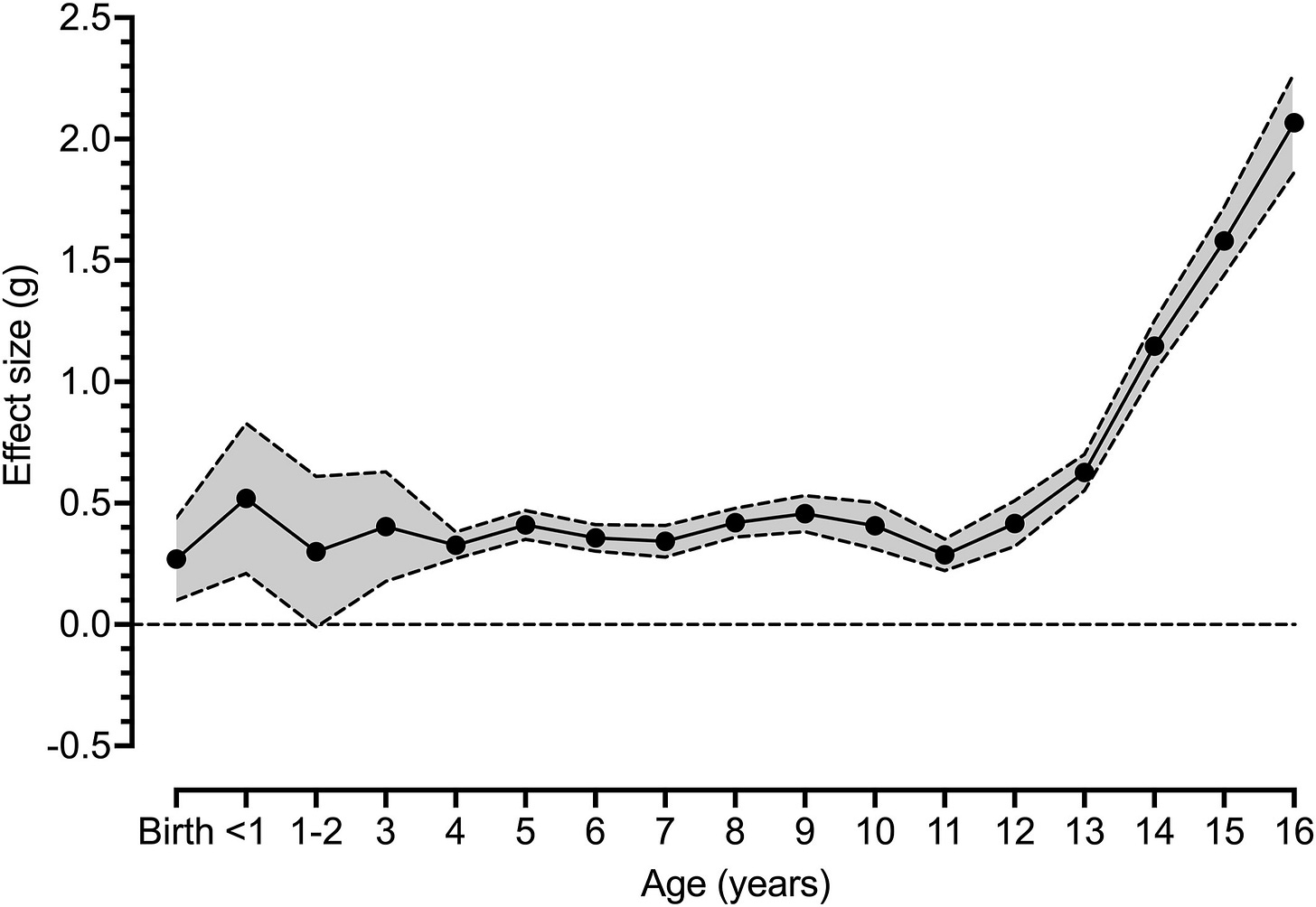

Harper and colleagues appear to suggest either that my two meta-analyses included only children who were nine years of age or older or that my two meta-analyses combined pre- and post-pubertal children into one large group. These suggestions are problematic. Meta-Analysis 1 included children as young as 1-2 days old, and I clearly presented the data by each year of development throughout the paper. The figure below was published in Meta-Analysis 1, and it clearly shows the sex difference in muscle strength presented at each year of development up until age 16.

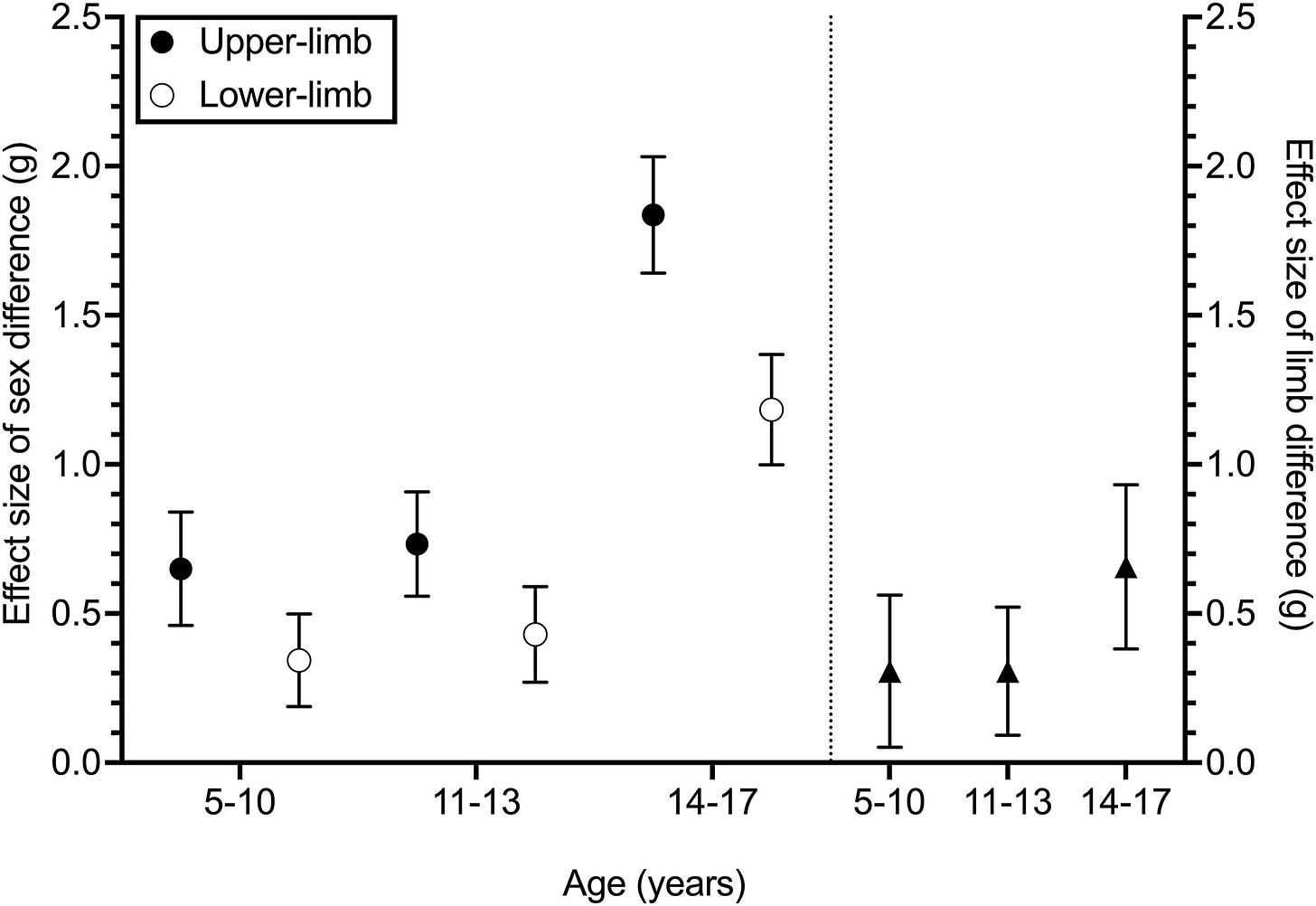

In Meta-Analysis 2, data from children between the ages of 5-10 years old were combined. Perhaps Harper and colleagues viewed this as a problem because some boys might have started puberty at around age 9. In Australia, about 7% of boyswho are 8-9 years old are said to have some initials signs of puberty according to their parents. Thus, Harper and colleagues’ critique about age of puberty carries more weight in Meta-Analysis 2, where children 5-10 years old were lumped into one average. However, their critique carries little weight when directed toward Meta-Analysis 1, because those data were analysed by each year of development from birth until age 16. Nevertheless, in Meta-Analysis 2, when I now compute a simple unweighted average across all sex differences in strength for only the 5-7-year-olds, I still find that boys are 5.4% stronger. If the 8-year-olds are added to this cohort, the boys are 6.6% stronger.

To summarize, Harper and colleagues’ critique about the age of male puberty is not relevant to Meta-Analysis 1, because the results were reported by each year of development between birth and age 16. Harper and colleagues’ critique about the age of male puberty carries more weight in Meta-Analysis 2, because data from boys between 5-10 years old were combined. However, only a small proportion of boys start puberty at those ages, and, if the results from only 5-7-year-olds are considered, boys are still approximately 5% stronger.

2. Harper and colleagues then attempted to discredit the relevance of my meta-analyses on grounds that my analyses examined muscle strength rather than athletic performance. On one hand, this is a reasonable critique, because the only athletes for whom strength tests are equivalent to actual athletic performance are competitive powerlifters and Olympic weightlifters. On the other hand, their critique is misguided, because one reason exercise scientists measure muscle strength is because it correlates with athletic performance or proxies of athletic performance. In other words, people who have stronger muscles (particularly relative to their own body masses) tend to run faster, jump higher, etc. In fact, in section 4.3 of Meta-Analysis 2, I referenced multiple studies that found correlations between muscle strength and vertical jump height, sprint times, and 100-m freestyle swim times in children and adolescents. Moreover, in Meta-Analysis 2, I pointed out that the finding of a larger sex difference in upper- than lower-limb muscle strength in children corresponds with the finding of larger childhood sex differences in track and field performances that rely more heavily on upper-limb strength (e.g., shot put, discuss, javelin) than lower-limb strength (e.g., 100- and 200-m sprints).

3. Harper and colleagues stated that my meta-analyses do not reveal the cause of the sex difference in muscle strength. That is true. My meta-analyses do not reveal the cause of the sex difference in muscle strength. However, in the Discussions of both papers, I clearly wrote numerous paragraphs explaining why sex differences in muscle strength before and after puberty are primarily biological in origin. I supported my conclusions with numerous references to other peer-reviewed studies.

4. Harper and colleagues said that both of my meta-analyses should “be rejected” from consideration in the case, because I did not follow PRISMA guidelines when conducting the literature search and analysis. This opinion is misguided for several reasons.

First, my searches uncovered more papers on the topic of childhood sex differences in muscle strength than previously discovered and submitted to analysis. Meta-Analysis 1 included 808 effects from 169 studies, which were conducted in 45 countries between 1961 and 2023. The total number of children and adolescents in Meta-Analysis 1 was 353,676. Meta-Analysis 2 was smaller in scale but still included 299 effects from 34 studies. The total number of children and adolescents in Meta-Analysis 2 was 6,634. The next closest meta-analyses on this topic are the papers by Thomas and colleagues in 1985 and 1991, but the whole point of my research was to update these two previous meta-analyses. Moreover, I have used my own search strategy in various reviews and meta-analyses that have ended up uncovering and summarizing more studies on topics than ever before accomplished. Examples include reviews and meta-analyses on eccentric versus concentric muscle fatigue, eccentric:concentric muscle strength ratio, the repetitions versus load continuum, and muscle strength in individuals with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). A fifth paper where I used this approach was my meta-analysis on sex differences in muscle fiber types. I published the results from this meta-analysis in 2023. This year, James et al. conducted a meta-analysis on the same topic. They followed PRISMA guidelines and found the same overall results that I found in 2023. Thus, just because a researcher does not follow PRISMA guidelines does not necessarily mean that their results are biased and worthy of being “rejected.”

Second, neither Harper nor any reviewers who have questioned me for not following PRISMA guidelines have ever named a study that they think I missed using my literature search strategies.

Third, my meta-analyses were peer-reviewed. Thus, other researchers weighed up any limitations of my methods against the positive aspects of the study. The peer reviewers determined that the positive aspects of the research outweighed any limitations.

Fourth, the confidence intervals around the effects sizes of the sex differences in muscle strength were narrow, particularly in Meta-Analysis 1. This narrowness indicates a high level of confidence in the findings. This high level of confidence occurred because data from thousands of boys and girls were included in my meta-analyses. Thus, even if I missed a paper or two in my literature search, adding the results from a paper or two to the analysis is unlikely to alter the findings in a meaningful way.

Conclusion

Harper and colleagues’ comments about my meta-analyses were misguided and sometimes inaccurate. Consequently, Harper and colleagues’ comments about my meta-analyses should not be weighted heavily in the Little v. Hecox case. Other researchers have also expressed concern about Harper and colleagues’ amicus brief.

How To Support My Ongoing Research on Childhood Sex Difference in Fitness

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you!

Great defense of your meta-analyses James.

Interesting that the 3 "professors" comprise a male "identifying" as a female, 2 "professors" of kinesiology, 2 are from Canada and 1 from Columbia University.

It would appear that the scientific method does not feature strongly in their disciplines or institutions.

Congratulations for being mentioned to the supreme court.

Even though they misrepresent you; they considered you to be a big enough fish to mention.

Even though I always knew that the fight for the truth is a fight forever; I had never expected the fight for the truth would be about such common sense thing as "boys are stronger than girls".

And look where we are.

Congratulations and keep up the fight.