[Skip to the end to see all the photographs!]

In 1972, President Richard Nixon signed Title IX of the Education Amendments Act into United States law. The broad aim of Title IX was to ensure, within federally funded educational institutions, that individuals were not discriminated against based on their sex. Men and women were to receive equal opportunities to participate in educational programs, including school sports.

“No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any education program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.” (Title IX)

The Problem

Over the years, Title IX has been used by some exercise scientists as a convenient reference for suggesting that women were almost entirely absent from the exercise and research conversation prior to the 1970s. As I have discussed in a previous essay and podcast, researchers Barabara Ainsworth and Catrine Tudor-Locke used Title IX as a rhetorical launching point for claiming that prior to Janet Wallace’s paper in 1975, there were no exercise intervention studies published in the journal Research Quarterly that included only female participants. In their review of that journal’s history, the authors suggested that increased research focus on women’s health and exercise experiences in the 1990s began in the 1970s with the passage of Title IX. Thus, their claim about women’s research participation was linked with their belief about the impact of Title IX. However, as I showed in 2020, there were at least 33 female-only exercise intervention studies published in Research Quarterly between 1930 and 1975. The 33 studies included approximately 5,000 female participants. Ainsworth and Tudor-Locke portrayed history inaccurately.

One issue with use of Title IX as a convenient bookmark for the start of female participation in exercise studies, is the implication that exercise researchers had little or no research interest in girls or women prior to that time. This bookmark is then further glued into place by the public health narrative that says women were historically excluded from participating in medical research trials. This latter narrative, which started in the early 1990s, and led to the creation of the Office of Research on Women’s Health, persists today, though it has been refuted multiple times.

Thus, within academia, there are continued issues regarding the accuracy of information surrounding female participants in early scientific research. My aim here is to provide further evidence – photographic evidence – challenging the belief that women were rarely included in early exercise and fitness research. However, before I do that, I will first explain how female participation can be expected based on surrounding historical events, and then secondly, I will briefly discuss how false narratives about female participants betray student learning.

Reasons to Expect Female Participation

The idea that women rarely served as participants in exercise or exercise-related research prior to the early 1970s is tempting to believe because female participation in school sports increased markedly in the years after Title IX. Naturally, the increased sports participation led to more research interest in female sports performance. However, just because Title IX caused increased sports participation among girls and women, and subsequently, increased research participation among girls and women, does not mean that women were absent from early research related to exercise. In fact, male exercise research participation also increased substantially after Title IX simply due to the overall expansion of university programs and professional opportunities in the field of exercise science.

Importantly, early research related to exercise often focused on characteristics of muscle fitness, such as muscle strength, muscle power, and muscle endurance. There are a few reasons why participation of girls and women would be expected in this type of research prior to Title IX.

For one, the science of exercise grew from fields like biology, medicine, physical education, and physical therapy. Knowledge of muscle fitness did not emerge directly from a field called sports science. That field did not yet exist, and its precursor, exercise physiology, was still coming on to the scene. Instead, knowledge of muscle fitness, which would have been some of the most relevant information on the capacities and limits of human physical performance at that time, emerged from various intellectual directions.

Second, school and university physical education classes would have still been split by sex prior to Title IX. Thus, female physical education professors and educators would have used “samples of convenience” in their research. These samples would have been the girls and women in their classes.

Third, much early research on muscle fitness originated in the field of physical therapy. Physical therapy, which developed in response to polio epidemics and the need to rehabilitate male soldiers injured in World Wars I and II, has always been a field dominated by female researchers and practitioners. In fact, the main professional organization of physical therapists in the United States, the American Physical Therapy Association, was, at the time of its founding in 1921, called the American Women’s Physical Therapeutic Association. Thus, as physical therapy often deals with the restoration of muscle function, and women would have made up most of the physical therapy researchers and students prior to Title IX, it would have been unusual if girls and women were not participants in this early research, particularly as many studies on muscle fitness are often first tested on healthy control participants who are samples of convenience – that is, the staff and students in the university’s physical therapy program.

We know that female samples of convenience were used in such research because scientists of that era told us so. For example, in her study on the effects of heavy resistance exercise on muscle strength, pioneering neuromuscular physiologist Frances Hellebrendt1 and her female colleagues tell us that the study participants were “[f]ifteen normal, healthy, women,” and that “[a]ll but 2 were connected with the Baruch Center’s physical medicine program, either as students or staff members.”

Student Learning

Given these reasons to expect female participation in early research, and given evidence that such participation does exist, claims to the contrary are unfair to students who are eager to learn about the nuanced history of women’s research participation. Based on the current narratives, a scholarly undergraduate student, let us call her Jane, might conclude, “Well, if females did not partake in many research studies prior to Title IX or the creation of the Office of Research on Women’s Health, then what is the point at looking through the archives of exercise, medicine, physical education, and physical therapy journals for information on women’s health and fitness?”

Yet, I know Jane is being told an incomplete story. I know this because I have gone through the inductive processes of identifying, downloading, and reading the archives of journals in the fields of physical education, physical therapy, and exercise science. I know, for example, that participants in strength training intervention studies before 1980 were more likely to be men than women. I know this because I was the guy who discovered, aggregated, and read all 339 relevant papers, and then tallied up the numbers of male and female participants and then published them. However, just because women were less frequent participants in specific types of exercise research, does not mean, prior to Title IX, that researchers did not care about women or study them.

When I look the archives of relevant journals, I see female participation scattered around in fascinating ways. I see researchers of both sexes, but mostly females, making gradual scientific progress in the study of female muscle fitness. I think Jane would appreciate this. I think Jane would want to learn more and go through her own inductive processes. I think Jane would be interested to read, for example, the results of surveys administered to high school girls in 1934 and university women in 1935 asking them to disclose their most and least favourite types of sports and physical activities.

I think Jane might also like to read a study by Anna Espenschade in 1936, which involved measuring the distances covered by female field hockey players during matches. When Jane reads that the distances were measured using an observation and manual tracing technique, she might look down at her smartwatch, humbled by history, and appreciate the technological advancements that have alleviated the burdens of some measurements.

If survey research and field measurements are not enough to satisfy Jane’s inquisitive mind, then perhaps the first study on “cross-education” will fill her void. Cross-education is the physiological phenomenon by which exercise training of one arm or leg causes the muscles of the other arm or leg to strengthen as well, even though the other arm or leg never performed any exercise. Cross-education was first observed in a study published in 1894. This study included two participants – both of whom were women and co-authors on the paper. Their names were Theodate Smith and Emily Brown.

Finally, if this small sample of example studies is still not enough to quench Jane’s thirst for knowledge, then surely the 1938 supplemental issue of Research Quarterly will do the trick. This supplemental issue described results from 96 physical education studies that were conducted at Wellesley College. Wellesley College was as an all-female university. Thus, all or most of the participants in these 96 studies would have been girls or women. Surely, Jane will appreciate that.

A Photographic History of Female Participation

My aim now is to provide further convincing evidence that women were participants in early exercise research more often than we are led to believe, and I have the photographs to prove it. These photographs are intriguing, informative, and sometimes humorous. They show girls and women performing various tests of muscle fitness. I am unaware of any previous attempts to identify such photographs and assemble them into one source. Thus, my goal is to literally show you female participation in early research on muscle fitness. As the saying goes, “A picture is worth a thousand words.”

The photographs come from 20 academic papers, which were published in medicine, physical therapy, and physical education journals between 1924 and 1968. Six of the papers were published in Research Quarterly, and most of the studies were conducted in the United States.

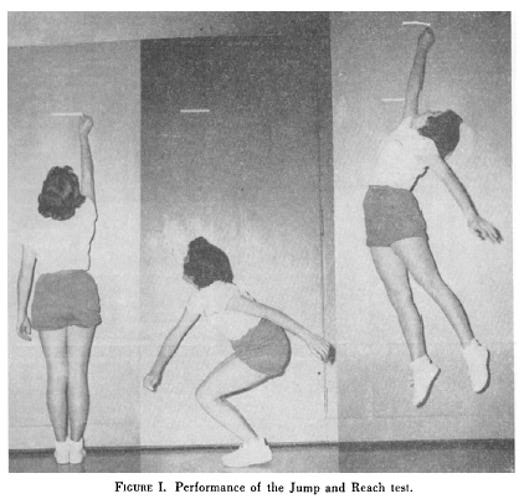

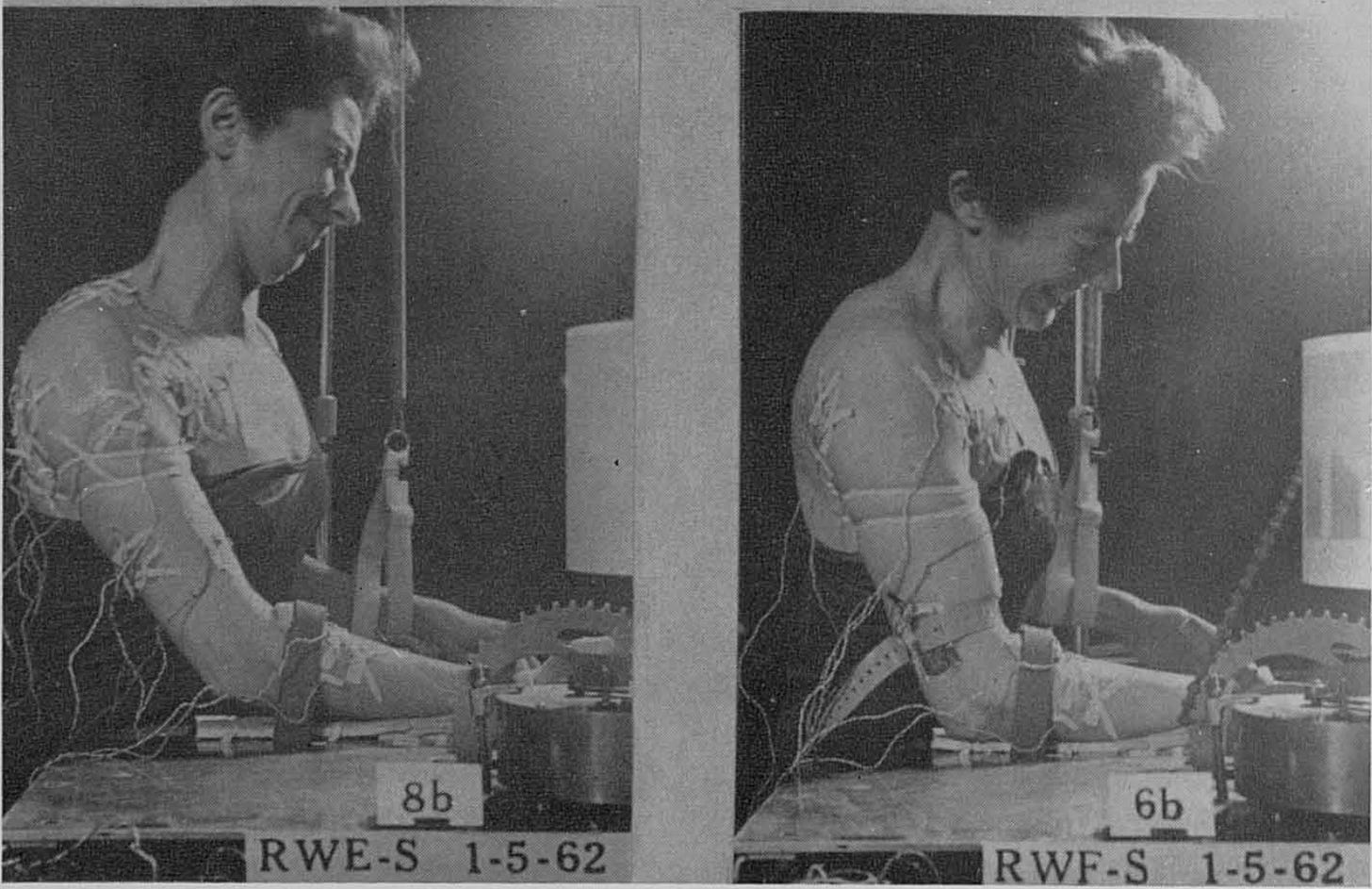

In the photographs, you will see girls and women performing various tests of muscle strength, muscle power, and muscle endurance. In Studies 1 and 10, for example, you can see women performing the vertical jump – a test of lower-body power. In Studies 13 and 16, which were conducted in the early 1960s under the guidance of Frances Hellebrandt, you can see women performing exhaustive exercise. The purpose of Hellebrandt’s studies was to understand the processes and experiences associated with muscle fatigue.

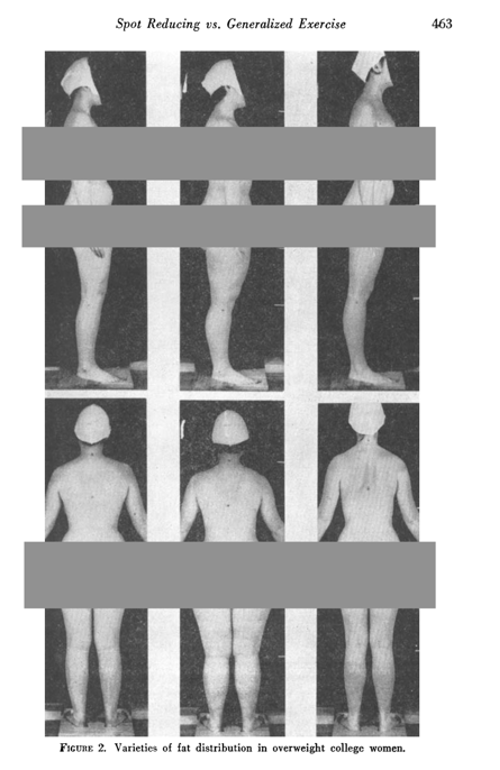

In Study 14, another experiment from Hellebrandt’s laboratory, you can see a group of women who were photographed naked. The aim of the study was to examine the effects of resistance exercise on body composition. At that time of the study, photography was an accepted technique for assessing body composition, and the naked body would have been the most accurate way to assess this. Moreover, this study by Hellebrandt and her female colleagues is historically important because it was one of the first attempts at testing whether physical exercise that targets specific body areas reduces the body fat in those areas – an idea called “spot reduction.”

Photographs of women exist in other papers of this era but are not provided below. I have focused only on studies that involved (a) women performing tests of muscle strength, power, or endurance, or (b) women participating in a strength training intervention. Photographs of women performing tests of flexibility, joint range of motion, or muscle stiffness can be also found in papers published before Title IX. Moreover, photographs would have been rarer in academic papers published prior to 1970 compared to today. Thus, the photographs below represent only a small number of studies from this era that included female participants.

Conclusion

In showing this photographic history of women’s participation in early research on muscle fitness, my goal has not been to convince you that women and men were represented in equal proportions. I do not know what these proportions are because the exact numbers have never been tabulated. I suspect, based on my specific examination of strength training intervention studies, that a 50/50 split during this era is unlikely. However, I also do not necessarily see this as a problem. Participant representations vary depending on disease prevalence, sample convenience, and the interests and willingness of the volunteers. Moreover, experimental research can be risky and discomforting. Though we now know, from decades of research and practical experience, that exercise is safe and beneficial for one’s health, during this era of human experimentation, there would have been some degree of uncertainty about the safety and appropriateness of physical exercise.

History is often complex and contains many interweaving stories, just as events, practices, and beliefs today are also impacted by a mix of factors. My goal has been to show a small portion of the fascinating history of women’s participation in early muscle fitness research. I want people to see the scientific equipment and the female participants and their effort, compliance, awkwardness, grimaces, and yes – their beauty. These are the things that can be saved by acknowledging that history didn’t start at Title IX.

Study 1 (1924)

Woman performing a vertical jump in a study that examined whether jump performance correlates with body height and weight. One hundred women participated in the study.

Source: Sargent LW (1924). Some Observations on the Sargent Test of Neuromuscular Efficiency. American Physical Education Review, 29(2) 47-56.

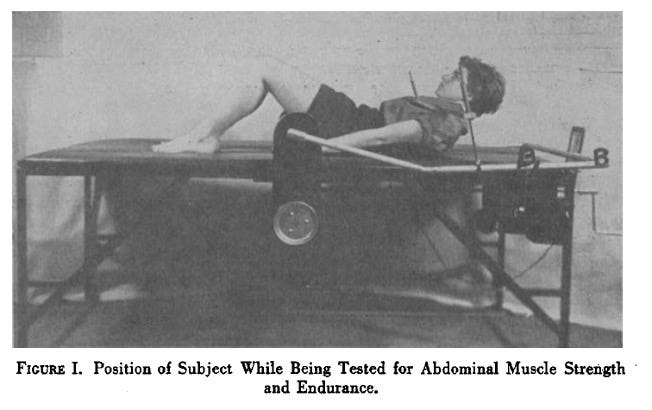

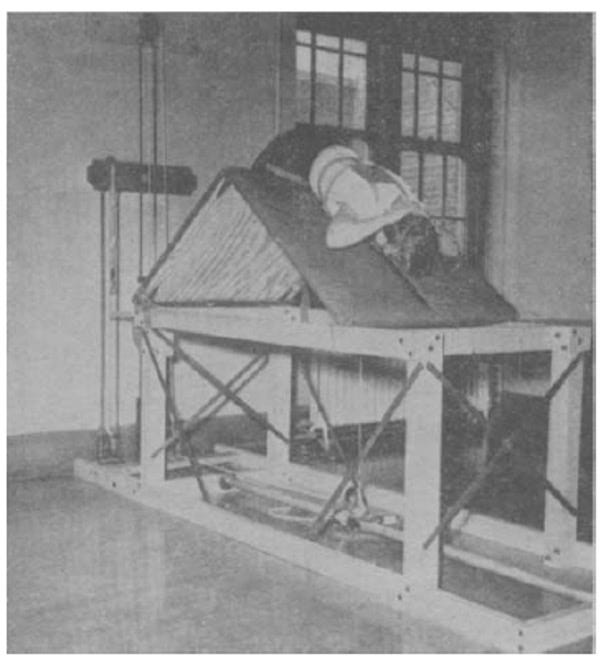

Study 2 (1933)

Woman tested on abdominal muscle strength in a study that examined whether abdominal muscle strength correlates with dysmenorrhea. One hundred and fifty women participated in the study.

Source: Hamer MC, Denniston HD (1933). Dysmenorrhea and Its Relation to Abdominal Strength as Tested by the Wisconsin Method. Research Quarterly, 4(1): 229-237.

Study 3 (1942)

Female polio patient tested on strength of the lateral trunk flexor muscles in a paper that described a method for measuring trunk muscle strength. The paper included case reports from female and male polio patients. It also included data of trunk muscle strength in 550 girls and boys between the ages of six and 16.

Source: Mayer L, Greenberg BB (1942). Measurements of the strength of trunk muscles. The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, 24(4): 842-856.

Study 4 (1950)

Female polio patient tested on strength of the elbow flexor muscles. The paper included results from muscle strength testing and resistance exercise progression in one female polio patient and two male polio patients.

Source: Wilson GD (1950). Power exercises in medicine. Southern Medical Journal, 43(1): 29-35.

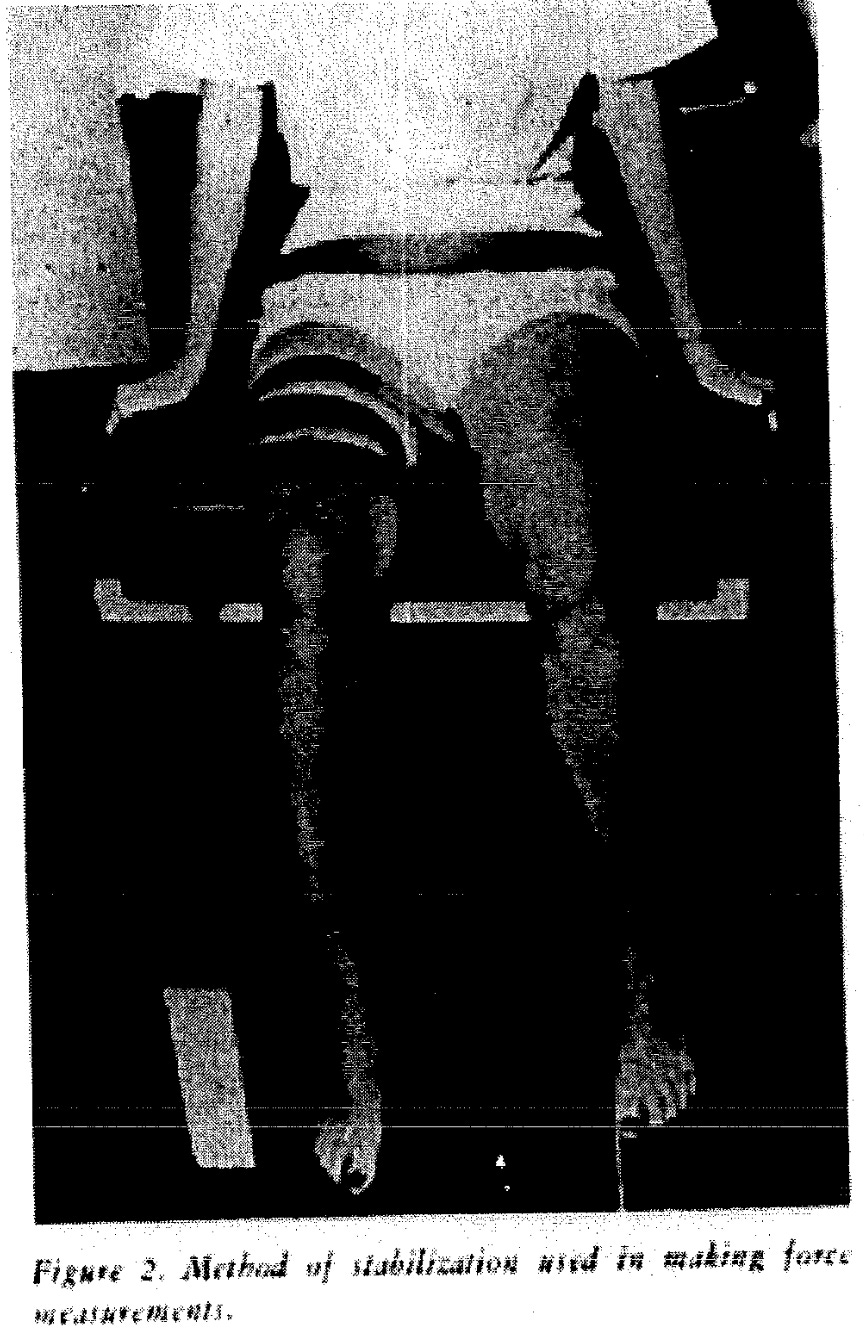

Study 5 (1952)

Woman tested on muscle strength of the right hip rotator muscles in a study that examined how joint angle and muscle length impact force production. Fifty women participated in the study.

Source: Jarvis DK (1952). Relative strength of the hip rotator muscle groups. Physical Therapy Review, 32(10): 500-503.

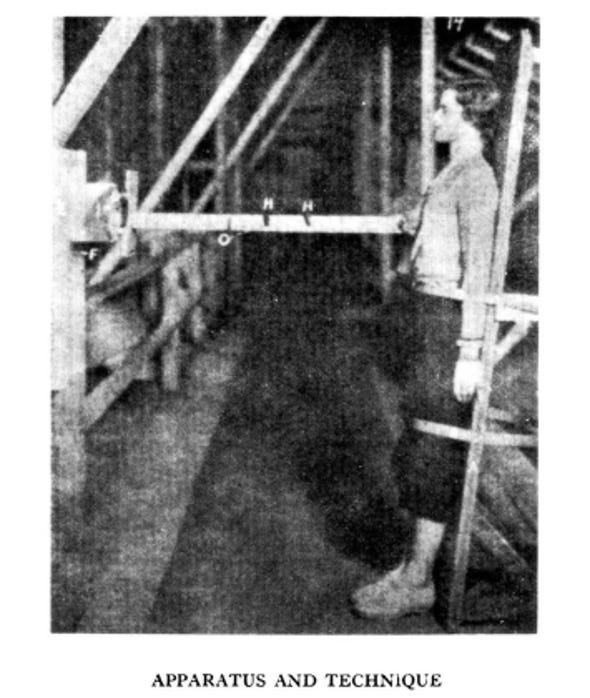

Study 6 (1953)

Woman tested on muscle strength of the left elbow flexors muscles in a study that examined how joint angle and muscle length impact force production. Thirty women participated in the study.

Source: Downer AH (1953). Strength of the elbow flexor muscles. Physical Therapy Review, 32(2): 68-70.

Study 7 (1955)

Woman tested on abdominal muscle strength in a study that examined the impact of an eight-week abdominal exercise programs on dysmenorrhea. Thirty-six women participated in the study.

Source: Harris RW, Walters CE (1955). Effect of prescribed abdominal exercises on dysmenorrhea in college women. Research Quarterly, 26(2): 140-146.

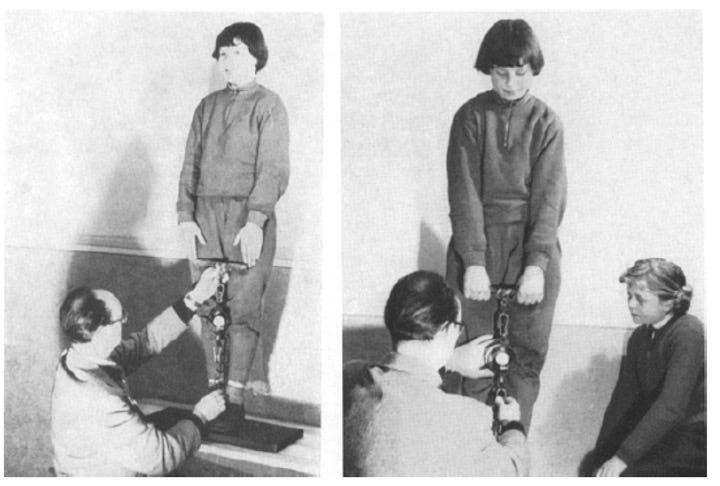

Study 8 (1956)

Girl tested on muscle strength of the left knee extensor muscles (i.e., quadriceps) in a study that examined the validity of different strength testing methods. A few hundred healthy and postpolio children (girls and boys) participated in the study.

Source: Beasley WC (1956). Influence of method on estimates of normal knee extensor force among normal and postpolio children. Physical Therapy Review, 36(1): 21-41.

Study 9 (1958)

Woman tested on low back muscle strength in a study that examined whether a resistance exercise program that targets the abdominal and back muscles relieves low back pain. Forty-six women participated in the study.

Source: Flint MM (1958). Effect of Increasing Back and Abdominal Muscle Strength on Low Back Pain, Research Quarterly. 29(2): 160-171.

Study 10 (1959)

Girl tested on vertical jump performance in a study that examined whether warm-up exercise impacts jump performance. One hundred and sixty-six girls participated in the study.

Source: Pacheco BA (1959). Effectiveness of Warm-Up Exercise in Junior High School Girls. Research Quarterly, 30(2): 202-213.

Study 11 (1960)

Woman tested on strength of the left knee extensor muscles (i.e., quadriceps) in a study that examined the impact of various resistance exercise programs on muscle strength. Seventeen women and seventeen men participated in the study.

Source: Bonde Petersen F (1960). Muscle training by static, concentric and eccentric contractions. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 48: 406-416.

Study 12 (1960)

Girls perform triceps extension exercise with dumbbells. The paper’s author detailed a weight training programs that girls can participate in as part of their school’s physical education course.

Source: Leighton JR (1960). Weight Lifting—For Girls. Journal of Health, Physical Education, Recreation, 31(5): 19-20, 80.

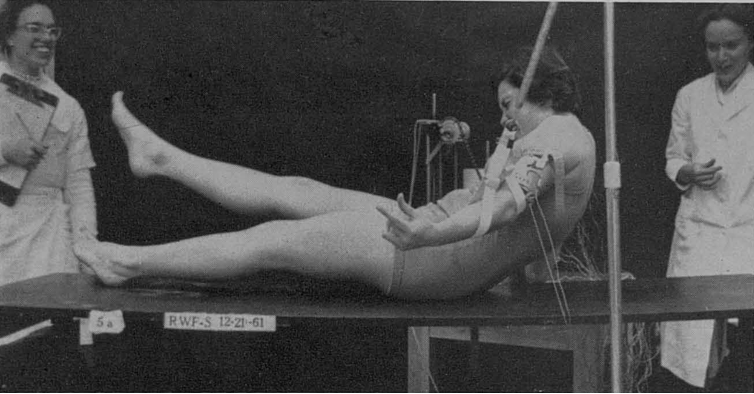

Study 13 (1962)

Women assessed on muscle endurance capacity in a study that examined how various parts of the body respond to localized exercise of the forearm that is completed until exhaustion. Thirty-two individuals participated in the study. Participant sex was not stated in the paper. All photographs in the paper were of female participants.

Source: Hellebrandt FA, Waterland JC (1962). Expansion of motor patterning under exercise stress. American Journal of Physical Medicine, 41(2): 56-66.

Study 14 (1962)

Three women assessed on body fat distribution with photography. This study, which was conducted by four female researchers, examined “spot reduction” versus generalized physical exercise on body fat distribution in 22 women. [I added the grey bars to the photographs].

Source: Schade M, Helledrandt FA, Waterland JC, Carns ML (1962) Spot Reducing in Overweight College Women: Its Influence on Fat Distribution as Determined by Photography. Research Quarterly, 33(3): 461-471.

Study 15 (1963)

Girl tested on muscle strength of the back and legs in a study that examined the impact of an isometric exercise program on muscle strength. Three hundred and twelve girls and two hundred and ninety-nine boys participated in the study.

Source: Kristen G (1963). [The influence of isometric muscle training on the development of muscle strength in adolescents]. Internationale Zeitschrift für angewandte Physiologie, einschliesslich Arbeitsphysiologie, 19(6): 387-402. German.

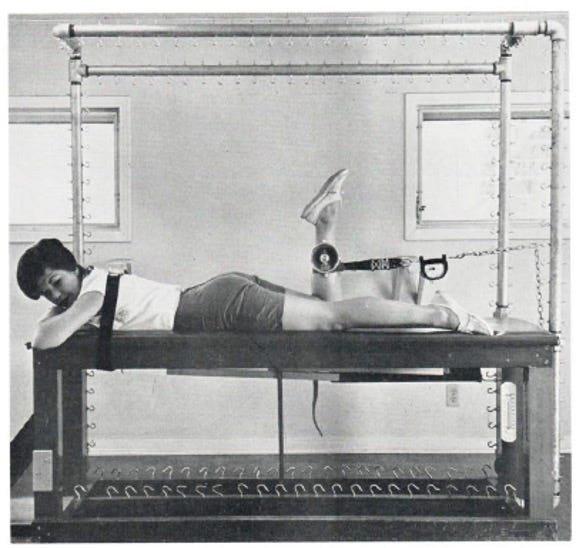

Study 16 (1964)

Women tested on muscle strength of the arm and forearm muscles in a study that examined changes in muscle activity during fatiguing exercise. Thirty-three women participated in the study.

Source: Waterland JC, Hellebrandt FA (1964). Involuntary patterning associated with willed movement performed against progressively increasing resistance. American Journal of Physical Medicine, 43(1):13-30.

Study 17 (1965)

Woman tested on strength of the knee flexor muscles (i.e., hamstrings) in a study that examined how joint angle and muscle length impact forces generated by muscles. Nineteen women and twenty-three men participated in the study.

Source: Campney HK, Wehr RW (1965). Significance of strength variation through a range of joint motion. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association, 45(8): 773-779.

Study 18 (1966)

Woman tested on strength of the elbow flexors muscles in a study that examined the reliability of strength tests. Thirty-three women and 20 men participated in the study.

Source: White SJ, Forward EM (1966). Serial changes in maximal isometric contraction of forearm flexor muscles. Journal of the American Physical Therapy Association, 46(10):1061-1067.

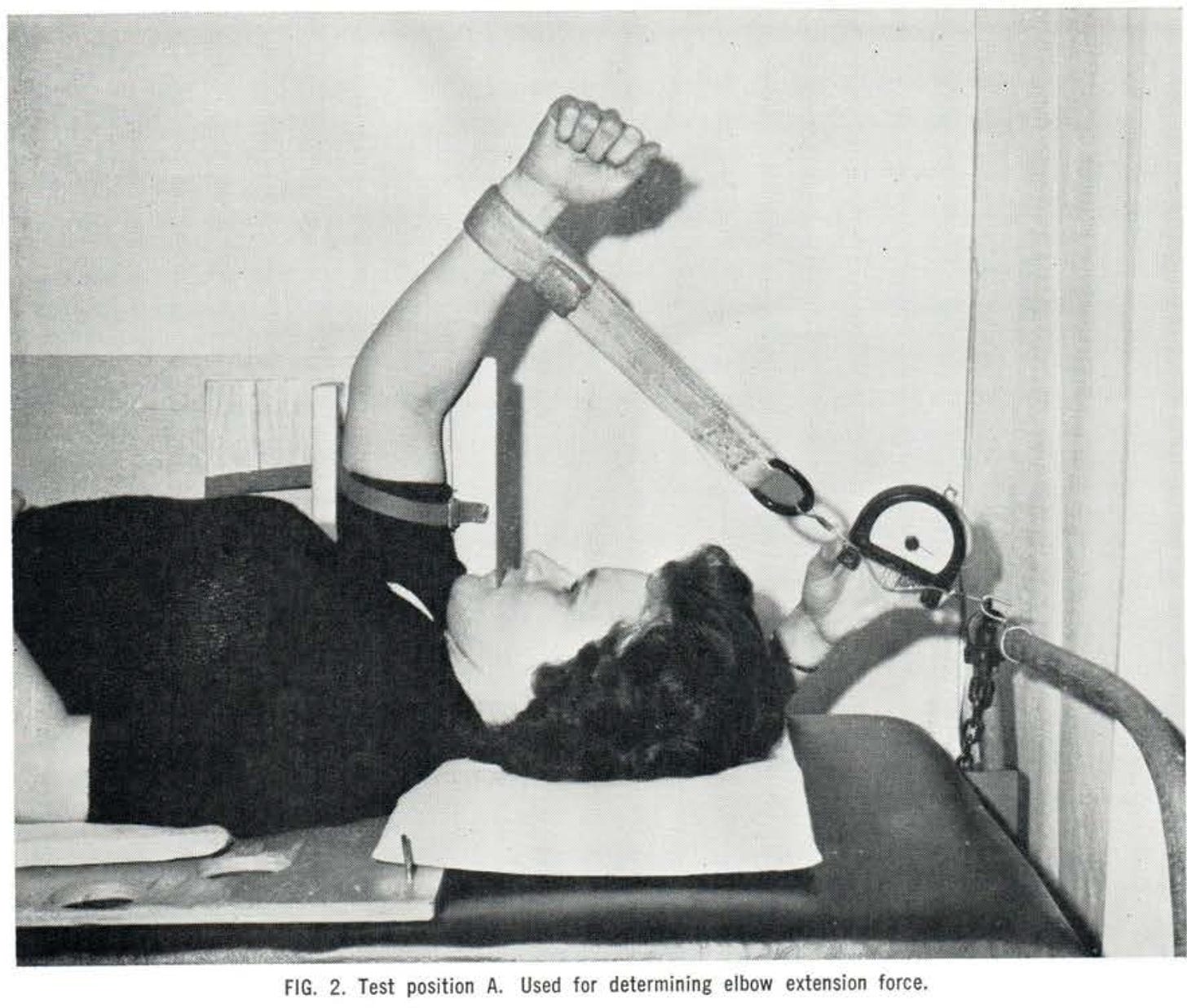

Study 19 (1966)

Woman tested on muscle strength of the left elbow flexors muscles in a study that examined how joint angle and muscle length impact force production. Sixty women participated in the study.

Source: Little AD, Lehmkuhl D (1966). Elbow extension force measured in three test positions. Physical Therapy, 46(1):7-17.

Study 20 (1968)

Girl tested on strength and speed of the right arm in a study that examined whether strength and speed correlate with each other and whether resistance exercise impacts these motor behaviours. Seventy-two eighth grade girls participated in the study.

Source: Payne LA (1968). The influence of strength on speed of movement in eighth grade girls. Research Quarterly, 39(3):653-661.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Frances Hellebrandt can be seen in the background of the photographs from Study 13.

Share this post