In June, the International Journal of Sports Physiology and Performance published a survey study on the history of exercise science. The survey, titled “Standing on the Shoulders of Giants: Essential Papers in Sports and Exercise Physiology,” was conducted by two accomplished exercise scientists – Jos de Koning and Carl Foster.

de Koning and Foster asked 52 male and female exercise science academics, who varied in subdiscipline expertise and who had been journal editors at some point in their careers, to each nominate 25 papers that they thought were “essential readings” for exercise science students.

de Koning and Foster conducted the survey because they observed that “many students [are] generally ill-prepared in terms of their understanding of the ‘deep history’ in exercise physiology.” The authors also stated that exercise science students seem to “do well with contemporary literature related to current research projects” but that student understanding of older literature is “deficient.”

de Koning and Foster’s study was much needed. Little information is available on the history of exercise science research, and this might partly explain why exercise science degree programs generally do not include courses or lectures on the history of the field. Moreover, exercise science has been one of the fastest growing academic majors in the United States over the past 20 years. Thus, thousands of exercise science students are graduating from universities each year without understanding where the knowledge in their field came from – who produced and how it evolved over time.

The 52 academics who were surveyed by de Koning and Foster nominated a total of 396 papers as “essential reading.” This list of 396 papers was then sent back to the survey respondents. The respondents were then asked to vote on the papers, and the 100 papers out of the list of 396 that received the highest number of votes were then considered the “100 essential papers in sports and exercise physiology.”

The top 100 papers, which ranged in publication date from 1923 to 2018, covered many topics within exercise and sports science. Consequently, de Koning and Foster organized the 100 papers by general theme – for example, “altitude,” “thermophysiology,” and “resistance training.” The themes with the greatest representations on the list were “muscle energetics/metabolism,” “aerobic work/VO2max,” and “performance.” Importantly, de Koning and Foster admitted that the list is somewhat biased toward sports physiology and performance, given the editors who were surveyed.

Nevertheless, the list of 100 essential papers will be a useful resource for exercise science educators moving forward, and de Koning and Foster deserve recognition for their contribution to the field. However, there was one aspect of the survey’s results that de Koning and Foster either overlooked, found too uninteresting to mention, or purposely ignored. That aspect was the sex of the authors of the top 100 papers.

The surnames of many of the “giants” on the reference list, and their sex, were already known to me. “Komi, P” is Pavo Komi, the Finnish biomechanist who was known for his research on the stretch-shortening cycle, and who passed away in 2018. “Hakkinen, K” is Keijo Häkkinen, another Finn, known for decades of research on resistance exercise for improved health and performance. And then there is “Costill, D.” – David Costill, emeritus professor at Ball State University, known for his research on muscle fiber types in athletes and the impact of microgravity on muscle physiology and function.

However, as the reference list for the top 100 papers included only the first initial of the author’s name, and because the survey covered subdisciplines whose researchers are less familiar to me, I was not certain exactly how many of the top 100 papers were written by men. To find out, I downloaded the reference list and conducted the relevant searches online to determine the sex of the authors of the top 100 papers in exercise and sports science history.

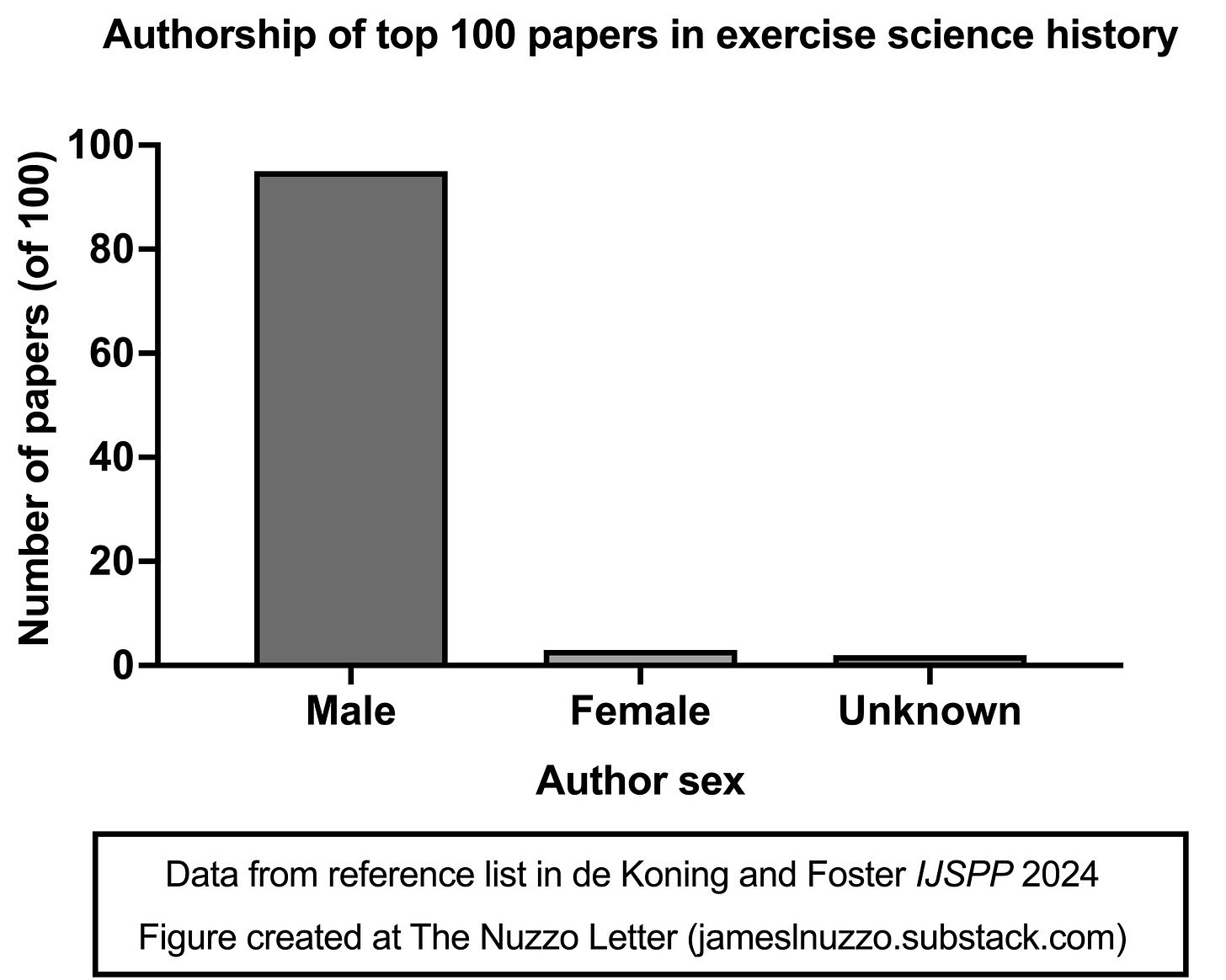

As shown in the graph below, only three of the top 100 papers in exercise and sports science history were written by women. Ninety-five papers were written by men, with author sex not applicable or indeterminable for two of the 100 papers. Thus, men authored 97% of the top 100 papers in exercise and sports science history. Nice work, boys!

Pointing out the supplemental fact that the giants of exercise science have been overwhelmingly male is not something I particularly enjoy. I do not to wish to emphasize sex or gender in places where one’s ideas and intellectual contributions are what is most important. de Koning and Foster might have omitted information on author sex for similar reasons.

That said, gynocentrism and misandry are running amok (see the archives of The Nuzzo Letter for examples). Consequently, in such an antagonistic environment toward men, men have a right, and a responsibility to their families, their communities, and most importantly, to their own self-esteem, to defend their purpose and existence in life. If gynocentrists in academia, politics, and the media are going to use sex as a sword directed toward the torso of men, then men have the right to counter by using sex as a shield.

In contemporary exercise science, there exist pockets of female researchers who fill journal pages with lists of grievances about how bad women have it in the field, portraying themselves as perpetual victims. Examples include papers published on “manels” at academic conferences and female underrepresentation in professorships and research study participation.

Reading between the lines written in these papers, one gets the sense that men are being blamed for the supposedly problematic current state of things. Reading the actual lines written in these papers, one also notices the inabilities of the authors to grasp the realities of sex differences in male and female psychology. Moreover, these types of papers – in both their content and tone – signify a lack of appreciation for what men – in their ambitious drives for knowledge, status, and the betterment of humanity – have done for everyone. This includes the female academics who now leverage off the knowledge founded by these male giants. Thus, men have every right to throw up their shields and highlight their role in leading the way in discovering of how the human body responds to physical exercise.

Women have also contributed to this exercise science knowledge base, and their work, just like anyone else’s work, deserves a level of recognition commensurate with the work’s impact on the field. Frances Hellebrandt, who I have discussed previously at The Nuzzo Letter, is an example of a female researcher who deserves such accolades, given the originality of her ideas and the substantial number of research outputs that she generated over her career. Interestingly, though Hellebrandt was conducting her research in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s – a time that should, according to contemporary authors, be associated with higher levels of misogyny, patriarchy, discrimination against women, and female underrepresentation, I have not found a single comment by Hellebrandt in her dozens of papers about such topics. I suspect she was too busy collecting data in the laboratory and writing papers to give a damn!

So, the first reason for men to bring sex into this discussion is because their sex is under attack. A second reason to highlight de Koning and Foster’s omission of author sex in the top 100 papers is that it might represent gamma bias. Gamma bias occurs when sex or gender is omitted from discussions about achievements, when those achievements are made by men, but includes sex or gender when those achievements are made by women. Gamma bias theory also posits that sex or gender is included in discussions about negative acts, when those acts are committed by men, but sex or gender is omitted from discussions of negative acts when those acts are committed by women. Importantly, one reason for exploring gamma bias in various fields, including achievements made in exercise science, is because gamma bias is thought play a role in the “male gender empathy gap.” To quote Seager and Barry:

“Such cognitive distortions, we believe, are leading to a systematic exaggeration of the negative aspects of men and masculinity within mainstream culture, and a minimisation of positive aspects. These embedded distortions could be having a significantly harmful impact on the psychological health of boys and men and therefore on our society as a whole, including the psychology profession.”

From the list of the top 100 papers in exercise and sports science history, and from my own research on the history of exercise research and the history of technological innovation in exercise equipment, we have clear evidence that men have stood as the giants of exercise science. They have acted like the Greek god Atlas, holding the weight of exercise knowledge on his shoulders. Consequently, advocates of “gender equity” and related narratives and initiatives in the field of exercise and sports science should be careful with what they wish and push for. They should take a moment to contemplate, “What will happen if Atlas shrugs?”

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.