I want you to pretend for a moment that today is your first day lifting weights at the gym. You have a hired a personal trainer to create and guide you through a resistance exercise program. In one of your first sessions with your personal trainer, they assess your maximal strength. They do this by testing, what is called, the one repetition maximum or 1RM. The 1RM is the maximal amount of weight that you can lift for a given exercise. For the sake of this example, we will say that your trainer has tested your 1RM on the barbell bench press exercise and found that the maximal amount of weight that you can lift one time is 100 pounds.

Such strength assessments are conducted by exercise professionals for a couple of reasons. One is to quantify how strong you are at the start of your program and then compare this to how strong you are at the end of weeks or months of training to determine if the exercise prescription was effective at increasing your strength. If your strength increases, this means you and your trainer are on the right track. If your strength remains the same or decreases over that time, the trainer will need to make the necessary adjustments to your future exercise prescriptions.

A second reason that an exercise professional might assess your 1RM is to have a better understanding of what weights to prescribe to you throughout your training program, particularly for exercise sessions where the trainer might not be available to supervise you. So, just as your physician might prescribe a medication with a specific dosing requirement, your personal trainer should do the same for your prescription of exercise. Your trainer should tell you how much weight to lift and how many repetitions you should be expected to complete when lifting that weight. For example, if your trainer believes that the most effective way to increase your upper-body strength is to have you complete the bench press exercise with a weight equal to 80% of your 1RM, this means that you will exercise with a load equal to 80 pounds, as your 1RM was 100 pounds. But the trainer should also provide you with a sense of how many repetitions you should be expected to complete when lifting this load. But how does the trainer do this? How do they know how many repetitions someone should be expected to complete for a given weight? This is the sort of question that can be answered by the field of exercise science.

The particular question that we are dealing with here is what is called the repetitions-%1RM relationship.* The repetitions-%1RM relationship is foundational knowledge within resistance exercise programming. This relationship tells personal trainers, strength coaches, and exercise physiologists approximately how many repetitions an individual can be expected to complete when lifting a weight that is a certain percentage of that individual’s 1RM.

For approximately 20 years, a table of the repetitions-%1RM relationship has been published in a textbook that is assigned to nearly all exercise science students when they learn about the theory and application of resistance exercise. This textbook, which I studied from and cherished as an undergraduate student at Slippery Rock University from 2002 to 2006, is authored by the National Strength and Conditioning Association or the NSCA. The NSCA is an international leader in the dissemination of knowledge on resistance exercise. Any student who seeks to work as a strength and conditioning coach or as a lecturer or professor of resistance exercise will typically be required to pass the NSCA’s coaching certification exam, which will involve memorisation of the table on the repetitions-1RM relationship.

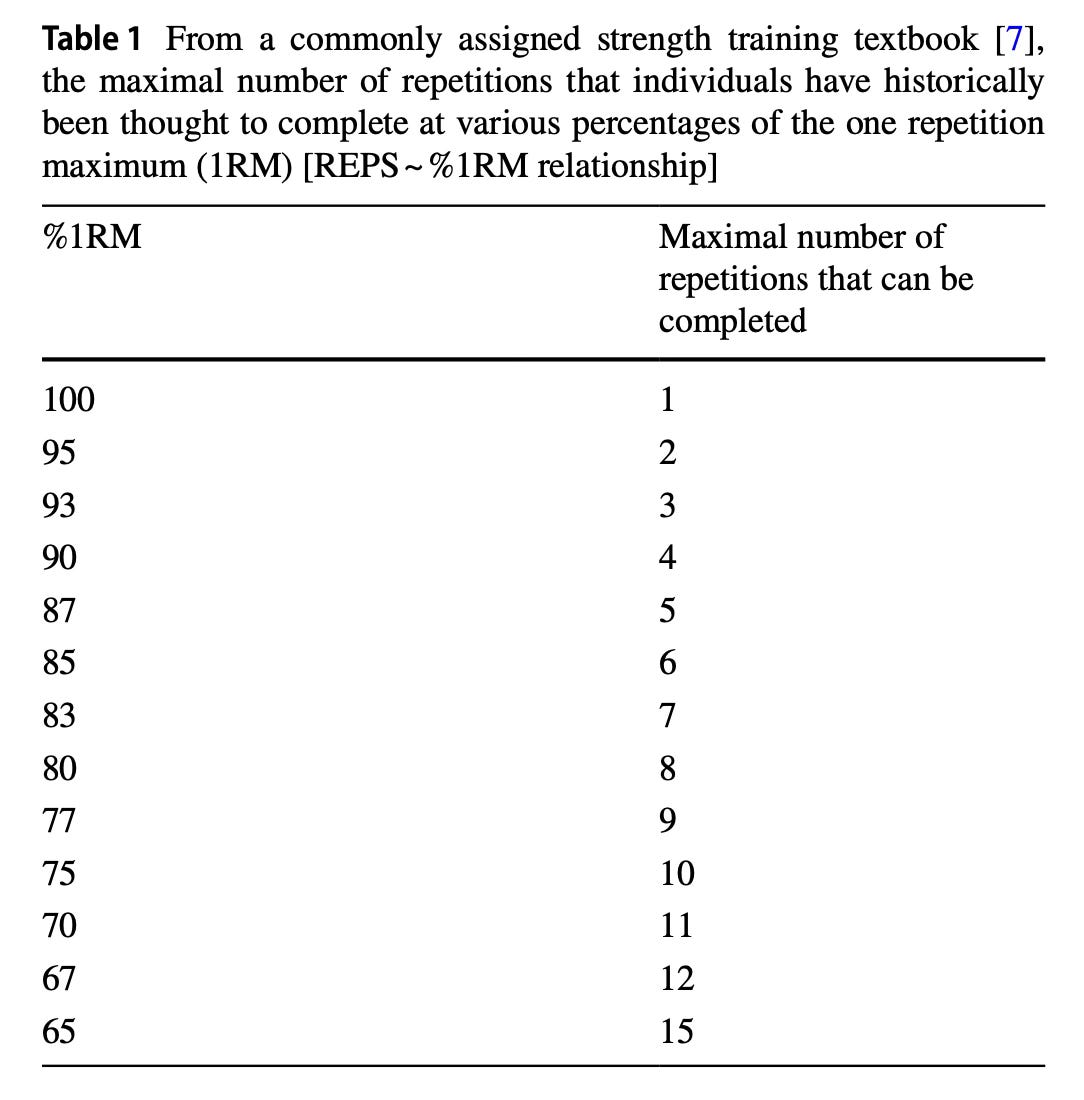

The NSCA’s table on the repetitions-1RM relationship, provided below, has two columns (see Table 1). The column on the left lists percentages of the 1RM, ranging from 65% to 100%. The column on the right lists the number of repetitions that an individual can be expected to complete with each relative load, assuming the individual gives their best effort to lift the load as many times as possible. When lifting a heavier load, which is closer to their maximum, the individual is predicted, as you might expect, to perform fewer repetitions than when lifting a lighter load.

NSCA TABLE OF THE REPS-%1RM RELATIONSHIP

For example, the personal trainer who prescribed to you a load equal to 80% of your 1RM on the bench press, would, based on the table, predict that you would be able to complete eight repetitions before then failing on your nineth attempt to lift the weight. However, if your personal trainer prescribed a weight equal to 65% of your 1RM, then the table predicts that you would be able to complete 15 repetitions.

However, various aspects of the NSCA’s table require consideration. First, the table was created from a small number of studies conducted a couple of decades ago. Second, in those studies, and others since that time, there has been some indication that the number of repetitions that an individual can be expected to complete might differ based on the exercise being assessed and characteristics of the individual such as their sex and whether they have previously participated in a weight training program. Finally, the NSCA’s table provides only a point estimate or single number of how many repetitions might be expected. It does not tell you the range of repetitions that an individual might be expected to complete at each relative load.

With all of this in mind, I chose to lead a research effort designed to re-evaluate the repetitions-%1RM relationship to determine whether the current NSCA table requires an update. My colleagues and I conducted a meta-regression to estimate the number of repetitions that can be completed at various percentages of the 1RM. We also explored if the relationship is moderated by sex, age, training status, and the exercise performed.

To do this, I searched the entire history of exercise research to find papers that reported results from repetitions-to-failure tests. A repetitions-to-failure test involves study participants being prescribed a given relative load and completing as many repetitions as possible with that load. In total, we identified 952 repetitions-to-failure tests which were completed by 7,289 study participants in 269 different studies, the earliest of which was published in 1961.

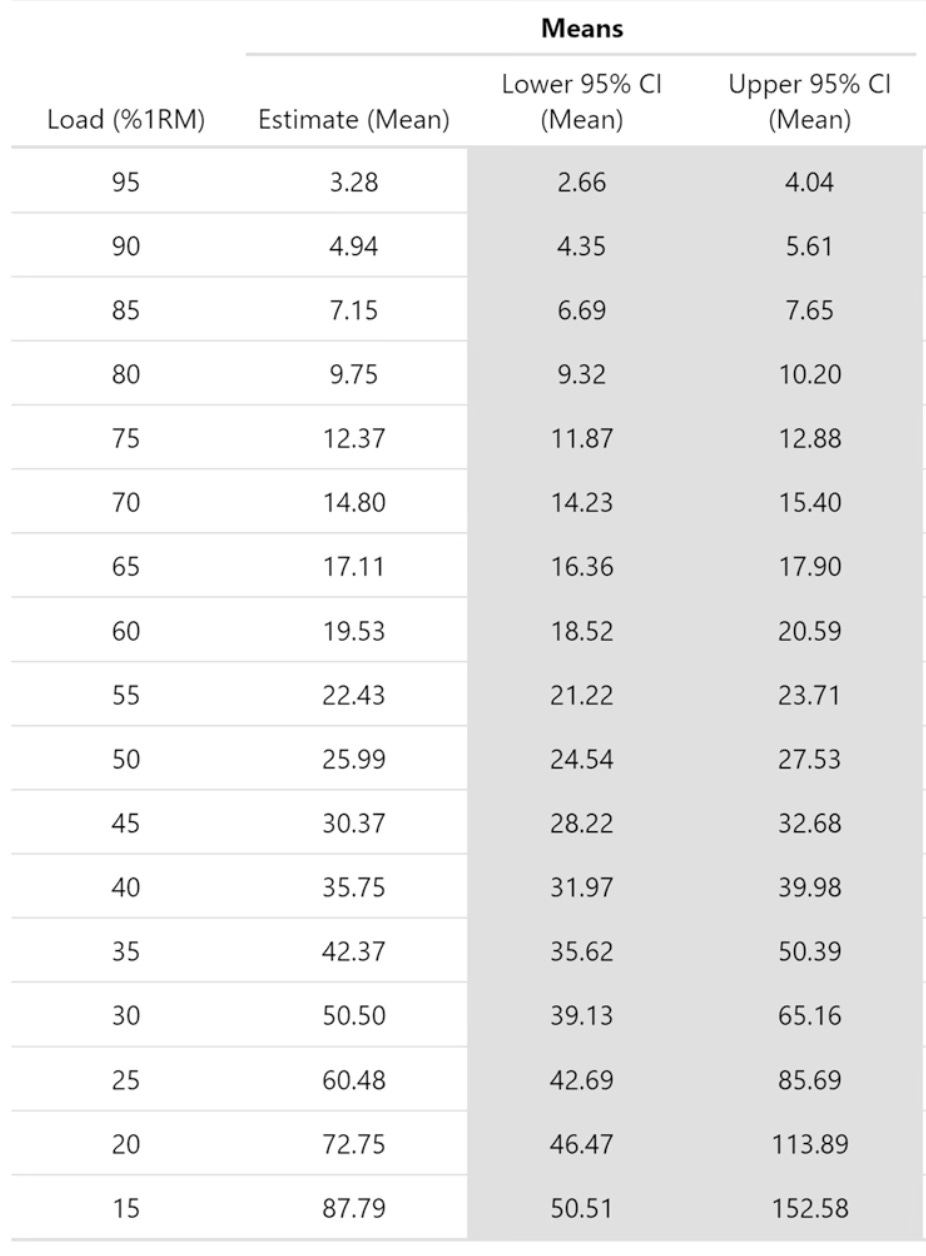

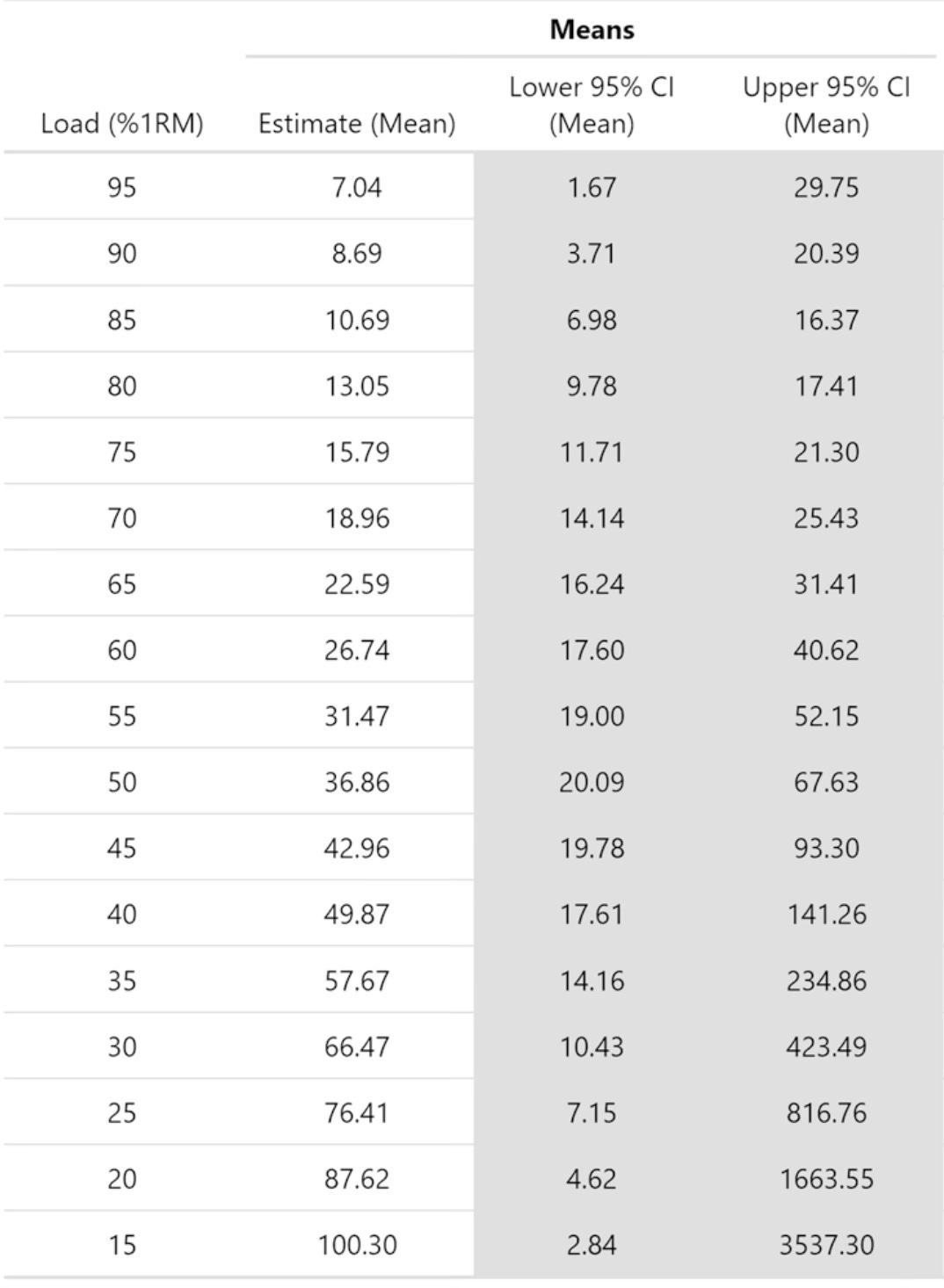

From the data, we were able to update the repetitions-%1RM relationship and generate a new table for students to learn from and for exercise professionals to prescribe exercise from. That table, provided below, includes a new point estimate for each relative load as well as the 95% confidence intervals. Compared to the NSCA’s table, our updated table provides slightly higher estimates for the number of repetitions that can be completed across the loading spectrum. Also, whereas the NSCA’s table provided estimates for loads as low as 65% of the 1RM, our table provides estimates for loads as low as 15% of the 1RM, though we acknowledge that such light loads are rarely used in most training programs and that the accuracy of the estimates generally becomes more imprecise with very light loads.

NEW MAIN MODEL TABLE

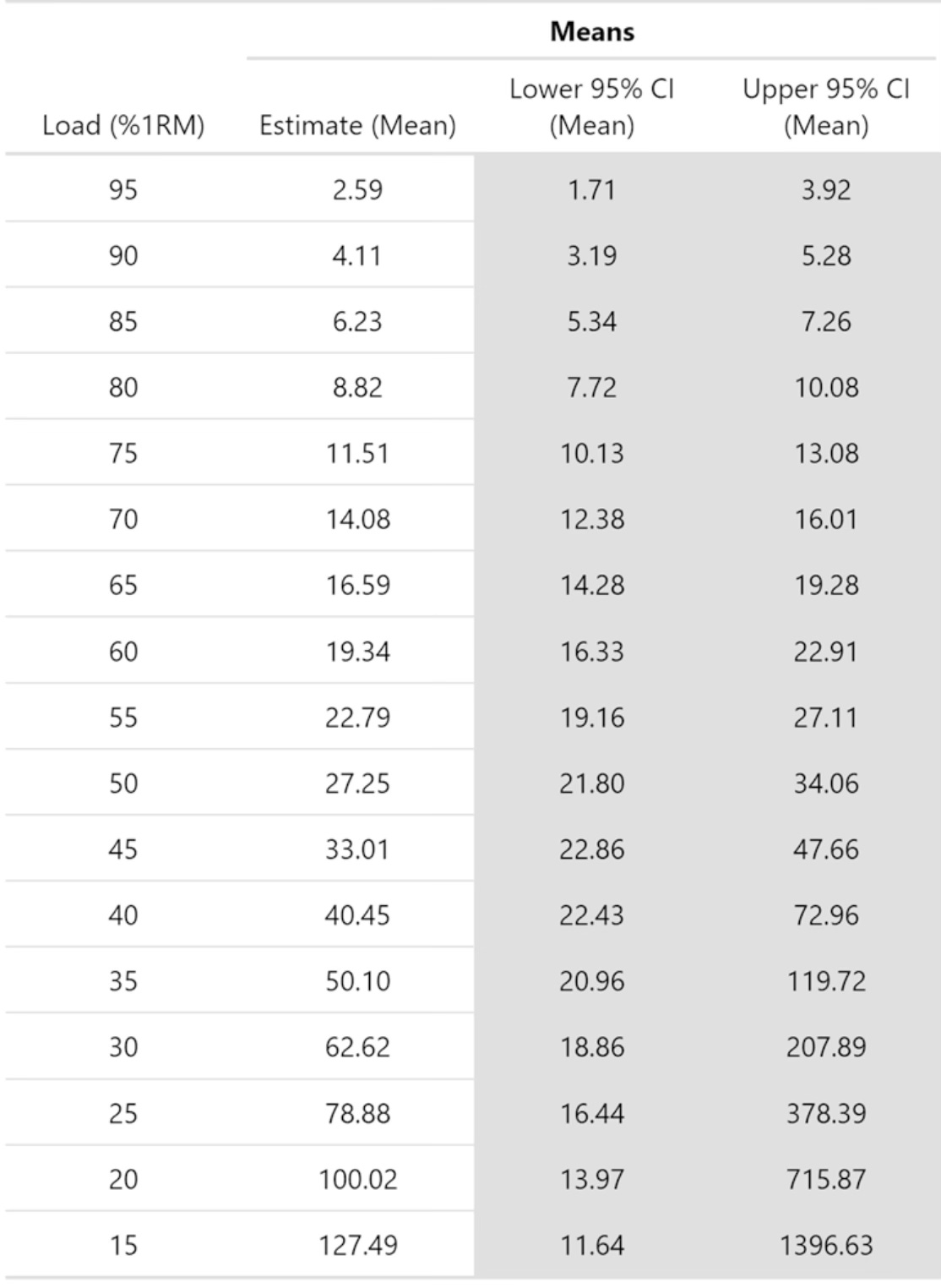

In our analysis, we found that sex, age, and previous experience with resistance exercise did not significantly impact the number of repetitions that can be expected at various relative loads. However, we found that the repetitions-%1RM relationship is not the same for all exercises. We found that the leg press is unique in this regard. At a given percentage of the 1RM, individuals can complete significantly more repetitions in the leg press exercise than in most other exercises. For example, there was a clear difference between the number of repetitions that could be completed during the leg press compared to the bench press.

In our hypothetical example, the personal trainer prescribed a weight to you for the bench press equal to 80% of your maximum. From our new table, you would be predicted to complete eight repetitions, which is also what the NSCA’s table predicted. However, if your trainer were to prescribe to you the leg press exercise and a weight equal to 80% of your leg press 1RM, you would be predicted to complete 13 repetitions before failing, according to our analysis. Consequently, we created separate tables for the leg press and bench press exercises. For all other exercises, students and exercise practitioners can refer to the new main table.

BENCH PRESS TABLE

LEG PRESS TABLE

In conclusion, after approximately 20 years of remaining stagnant and mostly unquestioned, we have updated the table on the repetitions-%1RM relationship, which is a fundamental concept in resistance exercise programming. Our contribution has been well received. My post about the paper on X has received over 400,000 views, which is a substantial number of views for a paper on strength training. Nevertheless, we caution readers to not think of the updated tables as newly ossified features of the field. Though we captured every piece of relevant data that we could find, collection of more data will be necessary if exercise practitioners desire tables to be created for other exercises, such as the squat, deadlift, lat pull down, seated row, and biceps curl.

Our paper has been published open access. So, download it for free, test your 1RM for a given exercise, calculate a percentage of this 1RM, and then see how many repetitions you can complete with that relative load. I look forward to hearing about your results. Feel free to post them in the comments. And who knows, the more you learn about the repetitions-%1RM relationship and your body’s own physical capabilities, you might realise that you do not need that personal trainer after all.

*In the audio, I have called the repetitions-%1RM relationship the “repetitions to 1RM relationship,” leaving out the word “percentage.” This was done for ease of verbal communication but it is technically incorrect. The correct wording is “repetitions to percent 1RM relationship.”

How to Support to The Nuzzo Letter

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for more evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post