These days, it is not too difficult to find an academic paper or news article that states that women are “underrepresented” as participants in medical research trials. In fact, in this week’s press release from the White House, in which it announced the creation of a White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research, the underrepresentation of women as participants in health research was mentioned in the press release’s first sentence.

By underrepresented, authors mean that women are being excluded from participating in research studies, or that researchers are not taking an interest in women’s health issues. This supposed exclusion of women from research is then thought to cause a lack of knowledge of how the female body works and how women might react to certain medical interventions differently than men.

The continued claim that women are not adequately represented in biomedical research is strange given that in 1990 federal legislation created the Office for Research on Women’s Health within the National Institutes of Health, or NIH. One of the main reasons the office was created was to ensure that women were equally represented as participants in clinical trials. In fact, the original claim that women were not equally represented in such research – the claim that led to the creation of the Office for Research on Women’s Health – was debunked in 1994 in a report generated by the Institute of Medicine. Moreover, in 1998, Sally Satel published an article titled, “There is no women’s health crisis,” in which Satel described the history of false assumptions about women’s health research in the US, including the false or questionable claims that women were underrepresented as participants in clinical research and that women’s health issues were not receiving adequate attention.

Nevertheless, the Office for Research on Women’s Health still exists today, and one of its main aims is still the inclusion of women as participants in clinical trials. In fact, there exist multiple offices within the US government dedicated to women’s health, and the White House’s Initiative on Women’s Health Research is set to establish several more offices. Meanwhile, no office for research on men’s health has ever been created within the US government; a strange omission given that life expectancy for men in the US is six years shorter than for women.

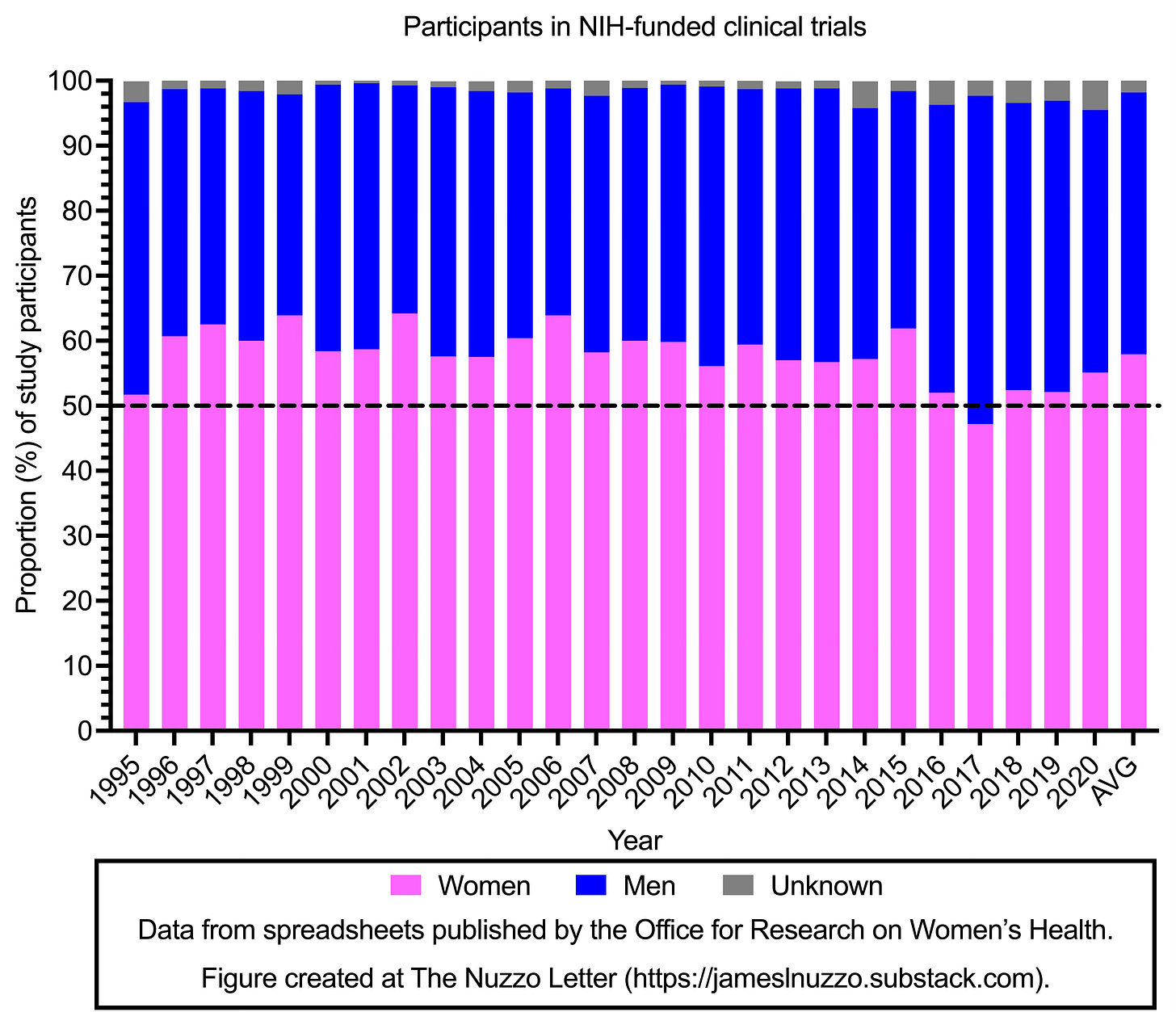

One unusual thing about the continued discussions on female representation in clinical trials is that each year, the Office for Research on Women’s Health publishes reports that state the proportion of male and female participants in NIH-funded trials. Because many people are unaware that these data exist, and because these data are often spread across multiple reports, here, my purpose has been to aggregate these numbers in one space so that the history of male and female participation in NIH-funded trials can be seen clearly and without need for further reference.

As can be seen in the graph, women have comprised over 50% of study participants in NIH-funded trials every year from 1995 to 2020, except for in 2017 when women comprised 47% of participants. In fact, between 1995 and 2020, women comprised, on average, 57.9% of participants in NIH-funded clinical trials each year, whereas men comprised, on average, 40.3% of participants each year, and 1.9% of participants were listed as unknown. In some years, the percentage of female participants was as high as 64%, while the percentage of male participants was as low as 35%.

Thus, data from the Office for Research on Women’s Health show that not only have women been adequately represented in NIH-funded trials, but they have been “overrepresented,” if one adopts the philosophy that representation should be 50/50.

Girls’ and women’s health issues are important, but so are boys’ and men’s. A fair and objective view on this issue would be that if government offices and initiatives are going to focus on sex and health, then there should be separate offices or initiatives dedicated to the two sexes. A women’s health office would focus on health issues that predominantly impact women. Examples include anxiety, eating disorders, arthritis, osteoporosis, chronic fatigue syndrome, and breast cancer. For men, such an office would focus on health issues that predominantly impact men. Examples include suicide, autism spectrum disorder, antisocial personality disorder, communication disorders, substance abuse, low educational attainment, homelessness, criminality and imprisonment, hearing loss, sleep-disordered breathing, spinal cord injuries, color blindness, and prostate cancer.

And of course, men and women have significant overlap in the health issues they experience, and these issues can be addressed independently or jointly by men’s and women’s health offices, or by entirely different health offices. In fact, one way to avoid debates that arise from the insertion of gender politics into public health policy, would be to abide by a philosophy that establishes national health offices based on specific health conditions, such as an Office for Research on Mood Disorders or an Office for Research on Muscular Dystrophy, rather than based on sex or gender.

For the administrative branch of the US government to declare another initiative for women’s health research and more women’s health offices is neither objective nor just. It is perhaps the result of the human biological inclination for helping and protecting women which is then jacked up on feminist and gender politics steroids. The US is not alone in this issue of gynocentrism impacting the public health agenda. In Australia, for example, where life expectancy for males is 4 years shorter than for females, the country’s national health body allocates about $88 million Australian dollars each year for women’s health research compared to $17.5 million dollars each year for research on men’s health.

As there already exist multiple national health offices for research on women’s health, this week’s announcement by the White House for an Initiative on Women’s Health Research suggests a sort of national emergency to address women’s health issues. But the epidemiological data do not support this position. Sally Satel astutely observed in 1998 that there was no women’s health crisis. Twenty-five years later, I am here to tell you that there is still no women’s health crisis.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated the time it took find, download, and extract data from government documents to make the summary of data on the proportion of male and female participants in NIH-funded clinical trials more easily understood, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for more evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post