On November 13th of 2023, the Biden White House and its Gender Policy Council announced the creation of the White House Initiative on Women’s Health Research. On February 23rd of 2024, the White House revealed the initiative would start with an investment of $100 million dollars into work being done by women’s health researchers and startup companies.

The $100 million dollars adds to the oodles of money already poured into women’s health research through government bureaus such as the Office for Research on Women’s Health (ORWH) within the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Nevertheless, this did not stop First Lady Jill Biden from saying that the reason taxpayers need to fund the White House’s new initiative is because we do not know enough about women’s health as a result of women’s health research supposedly being historically underfunded, or altogether lacking. Jill Biden also suggested that women’s health has not been a primary concern of society. The Associated Press quoted Biden as saying, “We will build a health care system that puts women and their lived experiences at its center…Where no woman or girl has to hear that ‘it’s all in your head,’ or, ‘it’s just stress… Where women aren’t just an after-thought, but a first-thought.”

In Australia, similar narratives about women’s health have recently emerged as part of the political and biomedical milieu. In announcing the Queensland state government’s $46 million dollar plan to build four free walk-in health clinics for girls and women, Health Minister, Shannon Fentiman said, “We know that historically, there has been a lack of investment in health services tailored to the unique needs of Queensland women and girls.” Moreover, in announcing a state inquiry into women’s experience with pain and the healthcare system, Victoria’s Premier, Jacinta Allan, stated, “For too long, women’s health has been seen as a niche issue and it has not had the attention or the support that it deserves.”

The claim that women’s health has been an “after-thought,” residing underfunded and understudied in the periphery of health research, has been made for many years. However, this claim has been untrue for much of its history. Gynoncentrism – the preoccupation with the needs, desires, and wellbeing of women – is rampant in biomedical and public health research. And here is some of the evidence to prove it.

Underfunded and underrepresented?

The NIH’s own data refute the claim that women’s health is underfunded. The table below was published in a report by the NIH’s Office for Research on Women’s Health in 2021. It shows that 11-14% of the NIH’s research budget funds studies that include only female participants, whereas 6% of the budget funds projects that include only male participants. The remaining 80% of the budget funds studies that include both male and female participants.

This funding of women’s health research then helps to explain why women are, in fact, not underrepresented as participants in medical research trials. This claim of female participant underrepresentation was first questioned by researchers in the 1990s, around the time the Office for Research on Women’s Health was created. The claim was then again debunked in 2001 in a three-page ripper of a paper by Ed Bartlett. What’s more, annual reports show that girls and women are not underrepresented as participants in federally funded research projects. And the publisher of these reports is the NIH and the Office for Research on Women’s Health!

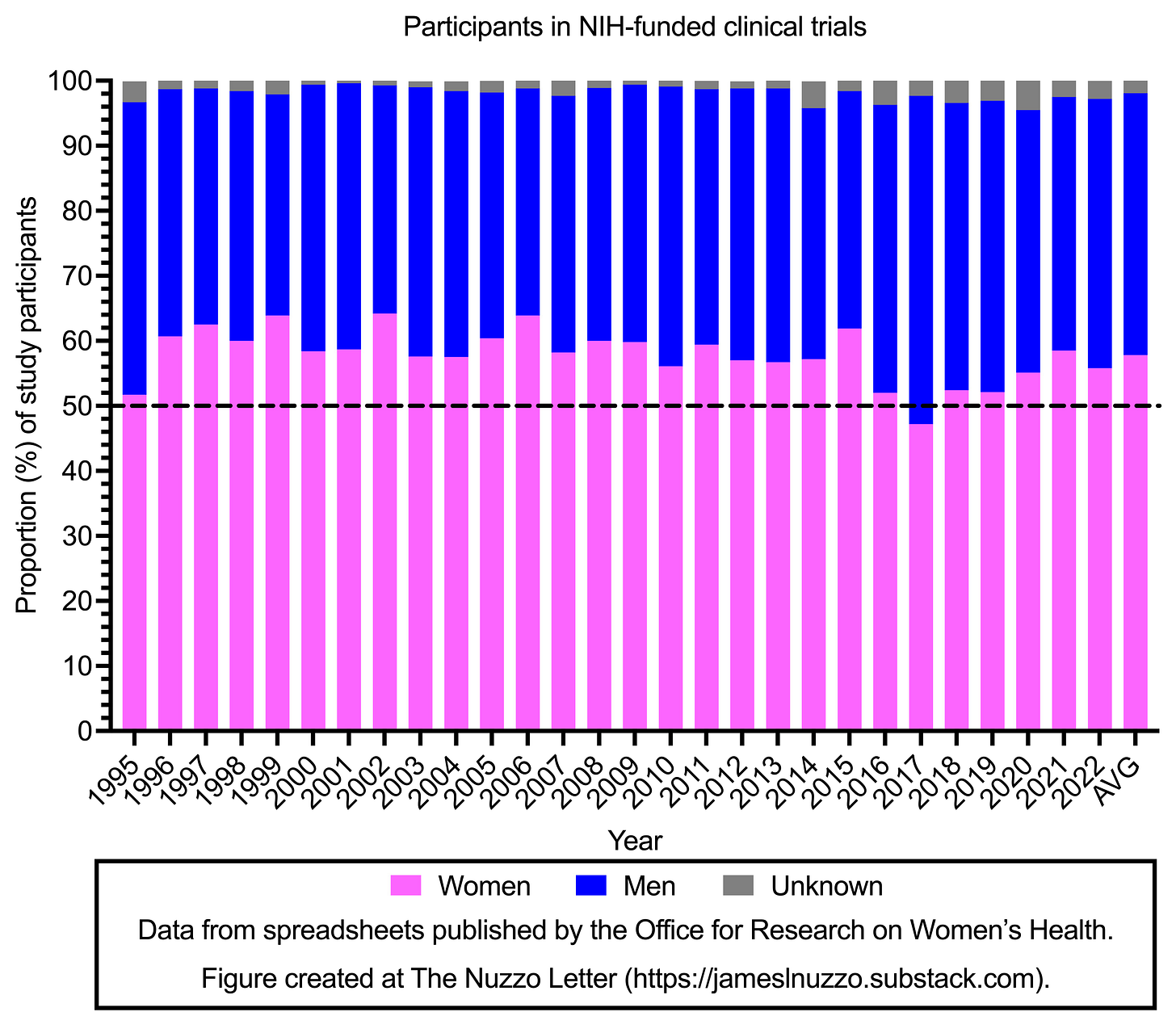

The figure below, which is an update of a previous graph published at The Nuzzo Letter, shows that for all but one year between 1995 and 2022, women made up a greater proportion of participants in NIH-funded research than did men. Averaged across all years, women made up 58% of participants in NIH-funded research between 1995 and 2022.

Just like the data from the NIH show major investments into women’s health research in the United States, data from Australia’s federal health bureau, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC), show the same. The table below, published on the NHMRC’s website, shows that for every year between 2013 and 2002, the NHMRC invested approximately five times more money into women’s health than men’s health research – all the while, the average Aussie bloke has a life expectancy four years shorter than his female counterpart.

PubMed search: “men’s health” and “women’s health”

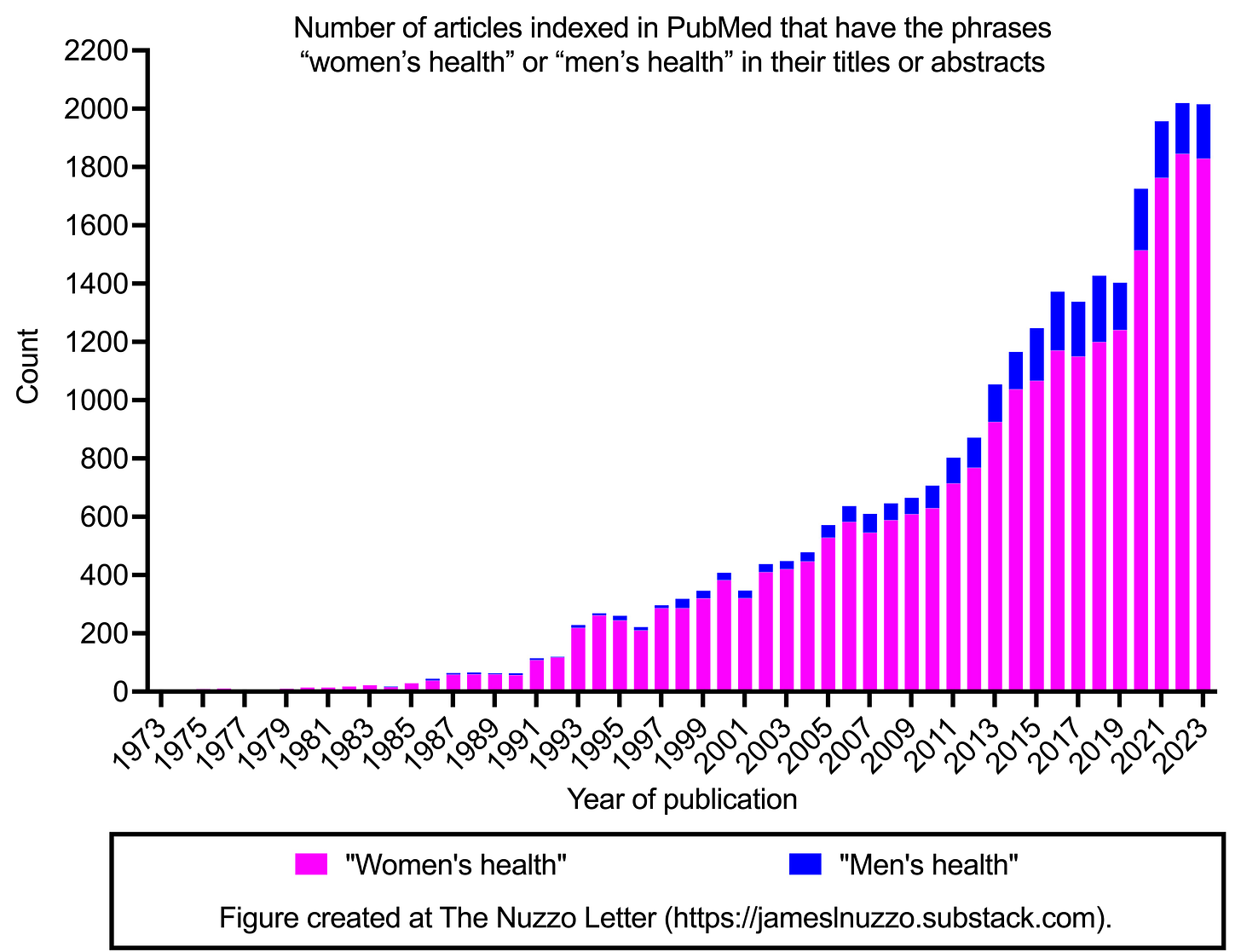

Another way to get a sense of how much attention men’s health and women’s health receive in research is to conduct keyword searches in PubMed. PubMed is a digital database of biomedical research articles. It is maintained by the NIH and the U.S. National Library of Medicine. PubMed indexes millions of research articles from around the world. PubMed does not index papers from every academic journal, particularly journals from the humanities, but it indexes most biomedical and public health journals. Thus, PubMed is an appropriate place to examine the amount of attention given to specific research topics.

Based on the claim that women are understudied, one would expect to find substantially fewer articles on “women’s health” than “men’s health,” when searching PubMed. But this is not the case. In fact, the opposite is true.

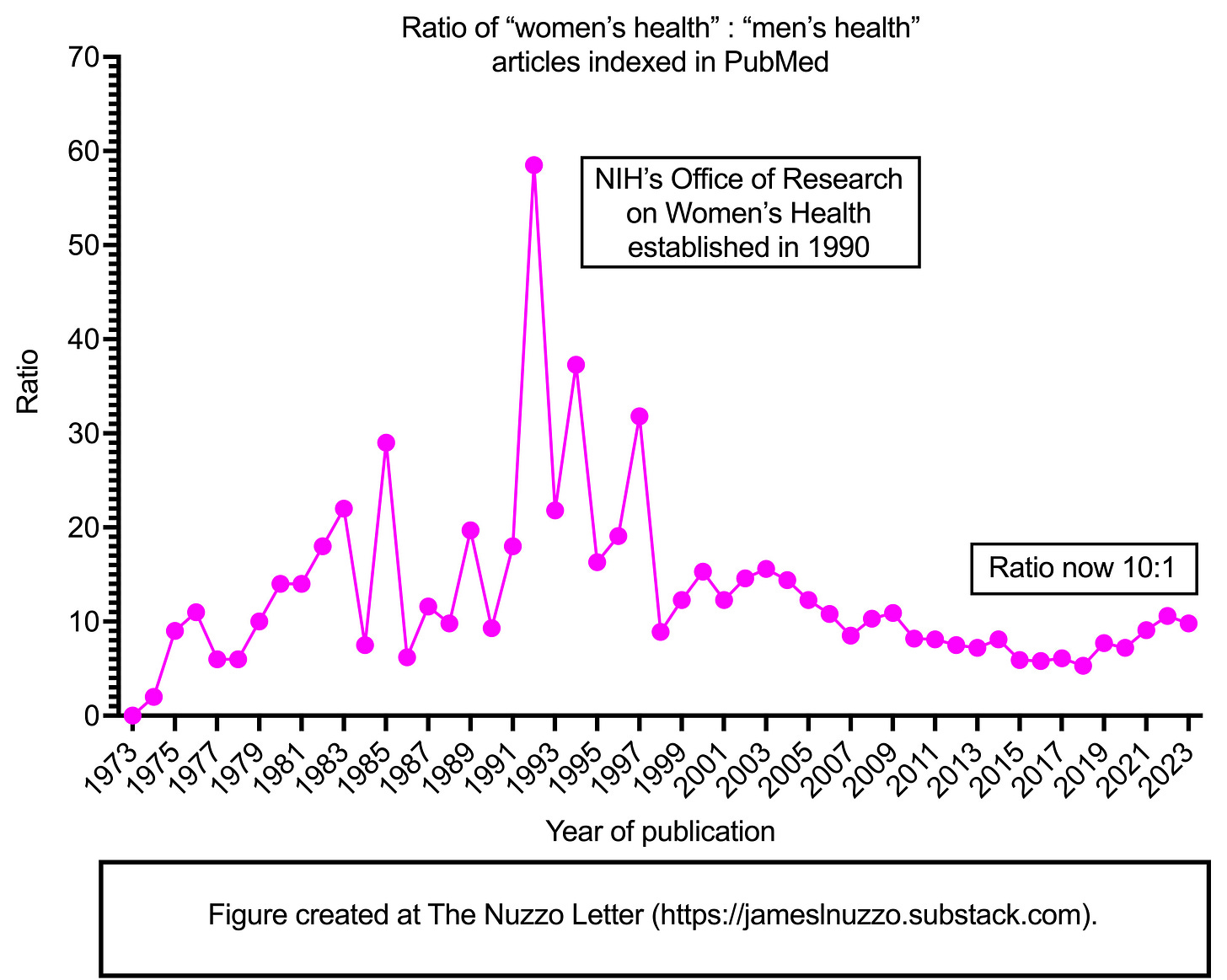

The bar graph below shows how many articles indexed in PubMed contain the phrases “women’s health” and “men’s health” in their titles or abstracts.1 Between 1973 and 2023, the phrase “women’s health” appeared in the titles or abstracts of 24,148 articles. Over that same 50-year period, the phrase “men’s health” appeared in the titles or abstracts of 2,804 articles. Thus, in contemporary biomedical and public health research, for every one article on “men’s health” that is published, there are 8-10 articles on “women’s health” that are published. This ratio is shown in the line graph below.

The results from the search of PubMed suggest that the phrase used to refer to the physical and mental wellbeing of men, “men’s health,” is not communicated as a broad abstract concept in the same way that “women’s health” is communicated as an abstract concept. Thus, to the extent that researchers, clinicians, and health officials want to move forward with men’s health as a broad area of interest, the term “men’s health” should be used more frequently. Lack of use of the phrase perpetuates the problem of relative lack of attention to men’s health because it signals that there are few health problems that are patterned among boys and men. On the other hand, frequent use of the phrase “women’s health” continues the ongoing (and often appropriate) attention to health problems that are patterned among girls and women.

Importantly, more frequent use of the phrase “women’s health” than “men’s health” is not the result of a reaction to decades of a supposed lack of interest in women’s issues or from the supposed exclusion of women from research trials. As I have explained, there is a lack of evidence of a disinterest in women’s health issues or of women’s exclusion from research trials.

Less frequent use of the phrase “men’s health” than “women’s health” is also not due to a lack of research on men. Males make up about 42% of participants in NIH-funded research trials, and searches for the words “male” and “female” and “boy” and “girl” in the titles and abstracts of articles indexed in PubMed reveal roughly equal numbers of articles for both sexes. Thus, researchers who study boys and men do not appear to be labelling their research as “men’s health” as often as researchers who label their research on girls and women as “women’s health.”

This then begs the question - why have scientists not framed their work on boys and men as “men’s health” research? Or conversely, why have so many researchers who study girls and women framed their studies as being about “women’s health”?

One explanation is gamma bias or a similar cognitive process that results in greater empathy for women than men and thus increased attention and funds directed toward something that is labelled as “women’s health.” Another, more practical explanation, is that researchers are incentivized to frame their research to be explicitly about “women’s health.” For example, research on “women’s health” might be more likely to garner media attention, because journalists who cover health news are more likely to be women, and women have a more pronounced in-group bias than do men. Also, government bodies are currently funding women’s health more than men’s health. Thus, academics are incentivised to frame their work as being about “women’s health” for purposes of acquiring future research funds.

Conclusion

In summary, I have provided evidence that women’s health is not, as Jill Biden claims, an “after-thought.” Significant attention has been paid to women’s health for many years. Continuing to deny this reality is determinantal to men’s health because it implies that there are relatively few issues affecting the lives of boys and men. However, this is not the case. Males have significantly lower life expectancies than females around the globe, and many factors that cause this lower life expectancy are preventable.

So, how can one help to straighten the gynocentric bent of contemporary biomedical research and its institutionalized funders? Many methods for correction exist. But perhaps one of the easiest methods is simply to write and orate the phrase “men’s health” – always truthfully, never apologetically, and much more frequently.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

To restrict a PubMed search to titles and abstracts, one need only to add the TI and AB operators to the search bar (i.e., “men’s health” [TIAB]). I chose to search only the titles and abstracts of articles because these components of articles are arguably the most important and influential. They are also the aspects of papers that are freely available to journalists and the general public.

Share this post