In November of 2020, the American Journal of Preventive Medicine published a paper titled, “Homicide mortality inequities in the 30 biggest cities in the U.S.” A few months after the paper was published, in April of 2021, I submitted a letter to the journal’s editor, challenging some of the ideas put forward in the paper. The editor rejected my letter. The reasons for the rejection were not entirely clear but projected insincerity.

The topic of race and homicide is relevant to the fields of male psychology and men’s health, and we are in need of open, honest, and evidence-based discussions about it. Thus, I have decided to publish the rejected letter here in full and without modification. I hope you will share it with others.

Dear Editor,

In “Homicide mortality inequities in the 30 biggest cities in the U.S.,” Schober et al.(1) reported Black individuals are more likely than White individuals to be victims of homicide in the biggest United States (US) cities. The authors sometimes referred to these mortality differences as “racial inequities” and suggested “structural racism” as one potential cause. The authors said their results can “inform city leaders in their efforts to address the homicide, violence, and racial inequities associated with them through the implementation of policies and programs”(1). The purpose of my letter is to ask the authors to explain why they did not discuss the characteristics (e.g., race, sex) of homicide perpetrators, and why they used the word “inequity” to describe the observed differences. Here, I explain why such information is important for interpreting the study’s results and thus important for informing future efforts to reduce homicide.

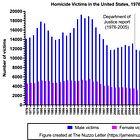

First, Black individuals commit more homicide than White individuals. According to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) (2), Blacks, who comprise ~13% of the US population according to the 2010 Census, committed 49% of all homicides in 2019 (n = 3,218). Whites, who comprise ~73% of the US population, committed 45% of all homicides in 2019 (n = 2,948) (2). Second, Blacks are typically killed by other Blacks. In 2019, 2,574 Blacks were killed by other Blacks, accounting for 89% of Black homicides (2). Third, Blacks are more likely to kill Whites than Whites are to kill Blacks. In 2019, 566 Whites were killed by Blacks, accounting for 17% of White homicides. In the same year, 246 Blacks were killed by Whites, accounting for 9% of Black homicides (2).

The authors also did not discuss perpetrator or victim sex (1). In 2019, males comprised 90% of homicide perpetrators and 72% of homicide victims (2). Acknowledgment of these two facts is important because lack of attention to men’s health is a problem in the US (3). Numerous national offices, policies, and initiatives have been created to address women’s issues but not men’s issues, though men fare worse than women on many outcomes (3). Also, acknowledgement of men’s issues should coincide with discussion on the decline of the two-parent household in the US, particularly among Blacks (4). Absence of the biological father in the household during childhood is associated with increased delinquency and criminal behavior later in life (5-7).

Finally, the authors used the words “inequity” and “disparity” interchangeably (1). The word “disparity” is causally and morally neutral. It is synonymous with the word “difference.” The word “inequity” implies lack of fairness or justice and thus infers causation. The authors did not discuss perpetration nor did they measure the cause of the racial difference in mortality. Thus, reference to the mortality difference as a “racial inequity” is inappropriate, as it would require identification of a cause that was somehow unjustly and disproportionately exuded onto one particular group. Racism as a cause is difficult to substantiate because most homicides are intraracial (2).

James L. Nuzzo, PhD

References

1. Schober DJ, Hunt BR, Benjamins MR, et al. Homicide mortality inequities in the 30 biggest cities in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(3):327-334. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.09.008

2. Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2019 Crime in the United States. Accessed March 15, 2021. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2019/crime-in-the-u.s.-2019/tables/expanded-homicide-data-table-6.xls

3. Nuzzo JL. Men’s health in the United States: a national health paradox. Aging Male. 2020;23(1):42-52. doi:10.1080/13685538.2019.1645109

4. Pew Research Center. Parenting in America: outlook, worries, aspirations are strongly linked to financial situation. 2015. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/12/17/1-the-american-family-today/

5. Beck AJ, Kline SA, Greenfeld LA, Bureau of Justice Statistics. Survey of Youth in Custody, 1987 (NCJ-113365). 1988.

6. Kroese J, Bernasco W, Liefbroer AC, Rouwendal J. Growing up in single-parent families and the criminal involvement of adolescents: a systematic review. Psychol Crime Law. 2021;27(1):61-75. doi:10.1080/1068316X.2020.1774589

7. U.S. Department of Justice. Family life and deliquency and crime: a policymakers’ guide to the literature. 1993.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for my evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post