Women as participants in research trials continues to be a hot topic. In one previous post, I presented data showing that, even though we often hear claims that women are underrepresented as research participants, data from the Office on Research on Women’s Health clearly show this to be untrue. Their data show that each year women comprise more than 50% of participants in research trials that are funded by the National Institutes of Health, or NIH.

The topic of representation of women as research participants is also a hot button issue within the field of exercise and sports science. Papers on this topic and in this field are typically written by women who go through exercise journals and tally the number of male and female participants in studies. Often, the authors find that men make up a greater proportion of participants than women. The authors then tend to conclude that bias against women is the cause of fewer female than male participants in the studies evaluated.

ays and peer-reviewed papers, I have explained the evidence that shows that women tend to be less interested and willing to participate in exercise and sports science research studies compared to men, and that such findings also need to be consider in any discussion about the causes of sex differences in research participant representations.

However, my purpose here is not to revisit the causes of sex differences in research representation. Instead, my aim here is to provide an example of how papers in the space of, what I call, “representation studies,” often include statements that are misguided or outright lies. The reason for taking the time to point this out is because such false or misguided statements, no matter how minor they might appear at the time, can have long-lasting consequences.

In 2020, I wrote a paper titled, “Correcting a historical error about female participation in training studies before 1975.” The paper was published in Quest, which is a lesser-known journal in the areas of kinesiology and exercise science, as it often deals with the humanities aspects of exercise rather than the biological or biomechanical aspects.

The idea for the paper came to me while I was working on historical research within the field. While conducting this research, I discovered a 2005 paper titled, “Health and physical research as represented in RQES.” RQES stands for Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, which is one of the most important journals in the history of exercise science, kinesiology, and physical education. The journal was founded in 1930 under the name Research Quarterly, and it published many foundational studies. For example, much of what we know about how many sets and repetitions we should complete while in the weightroom comes from studies published by Richard Berger in Research Quarterly in the 1960s and 1970s.

So, what was it about the paper from 2005 that grabbed my attention? As I mentioned earlier, Research Quarterly was founded in 1930. Thus, 2005 was 75 years from the journal’s founding. The 2005 paper was a 75-year commemorative overview of the journal. In the paper, the authors, Barbara Ainsworth and Catrine Tudor-Locke, summarized historical trends of health and physical activity research published in the journal, noting key research themes along the way. The authors covered various themes, but the one that caught my attention was the opening section titled, “Women.” In this section of their paper, the authors discussed females as participants in studies published in Research Quarterly throughout the journal’s history. The first sentence of this section reads as follows: “In 1975, Janet Wallace from San Diego State University published the first training study in RQES that focused on women.” Before I tell you why this sentence caused me to furrow my brow, let me first explain what a “training study” is.

In exercise research, a training study is when a group of participants complete an exercise or motor skill intervention that is designed by the researchers and consists of multiple training sessions that last a minimum of one week, but usually four or more weeks. By taking measures of the participants’ health, skills, or function at the start of the study, and then re-assessing these outcomes a few weeks later after the participants complete the intervention, researchers can determine whether the intervention was the cause of any observed improvements in the outcomes over the study period.

The reason I was surprised by the authors’ claim that the 1975 study by Janet Wallace was the first training study in Research Quarterly to focus on women was because of the historical research that I was conducting at the time I came across the claim. I had been diving deep into the archives of journals like Research Quarterly for my research on the history of strength training research. Based on my memory from my informal browsing of the archives, I was 100% sure that girls and women were regular participants in early studies published in Research Quarterly, and I was pretty sure that I had seen at least one exercise training study before 1975 that involved only female participants. The study that came to mind was one conducted by four female researchers in 1962 that sought to determine if exercise that focuses on a particular body part causes fat loss of the body part exercised – a concept known then, and now, as “spot reduction.” I thought for sure the participants in that study were overweight women.

Also, at the time I came across the 2005 overview, I was noticing a rise in the number of papers published on female participant representation in exercise and sports science journals. Conclusions reached in these papers were often questionable, and I had a feeling that the paper by Ainsworth and Tudor-Locke would start to be cited by contemporary authors as evidence of the historical exclusion of women from early exercise research.

Having a hunch that the historical claim was inaccurate, and to bring clarity to my own understanding of male and female participation in early exercise research, I downloaded the entire archives of Research Quarterly and searched for papers that might prove the claim to be untrue. For my analysis, I defined a training study as “an examination of the effects of a physical activity intervention of ≥ 1 week on any physical or mental health outcome.” Because the claim was specifically about studies that “focused on women,” I also deemed eligible only those studies in which girls or women were the soleparticipants in the study.

So, what did I find?

Between 1930 and 1975, Research Quarterly published 33 female-only training studies! Thirty-three! The types of training programs included general physical education, dance, stretching, golf, tennis, badminton, swimming, calisthenics, cardiovascular exercise, and strength training. The total number of girls and women who participated in these 33 studies was 4,960. Thus, the specific claim that there were no training studies published in Research Quarterly prior to 1975 that focused on women was entirely untrue.

Moreover, there are also seems to be a general message from Ainsworth, Tudor-Locke, and others who write about female underrepresentation in exercise studies that there was little concern about women and women’s issues within early papers in the field prior to landmark points such as the passage of Title IX or the creation of the Office for Research on Women’s Health within the NIH. However, this general message is also untrue. For example, if one looks through the archives of Research Quarterly for exercise-related studies that are not training studies, one will find that girls and women were often participants in many early studies. In Research Quarterly, these female-only non-training studies covered various topics such as physical fitness norms for girls and women, correlations between aspects of fitness in girls and women, the impact of exercise on the menstrual cycle and vice versa, and interest in and attitudes toward physical activity participation among girls and women. And these are only the studies that were exclusive to female participants. There exist many other studies in the journal’s archives that included mixed-sex samples of both male and female participants. Also, in 1938, Research Quarterly published an entire supplement issue that included results from 96 studies conducted at Wellesley College – a women’s university.

Based on my findings, I hope I have encouraged you to view papers that decry underrepresentation of female participants in exercise and sports science journals with an initial degree of scepticism. I believe correcting historical errors on this topic is important. I believe authors, myself included, should be held accountable for the incorrect things they say in their research, because of the potential for longstanding consequences. For example, given that the claim in question was published in a 75-year commemorative paper for the journal, a student or professor who reads the paper is likely to think the paper contains accurate and important information. Thus, the student or professor is likely to reference the claim without much deliberation. Consequently, such false claims can quickly propagate throughout academia and beyond. Also, as I have explained previously, the NIH’s Office for Research on Women’s Health was founded in 1990 based on the false claim that females were underrepresented in clinical trials in the United States around that time. The Office still exists today at taxpayer expense, and the narrative about female underrepresentation in research trials plays a part in hindering national-level recognition of boys’ and men’s health issues. Thus, misguided claims about participant representations can have lasting impact on policy and practice.

I would like to end by sharing another reason why I believe it is important to call out researchers for their false claims. That reason is that researchers who make false or misguided claims in one paper are likely to do the same or similar elsewhere, even if the topic they are speaking on is slightly different.

Let me explain.

In 2018, I published a letter that critiqued the American College of Sports Medicine’s (ACSM) consensus statement on the goal of creating health equity between demographic groups by achieving physical activity equity. One of the conclusions reached by the eight authors of the consensus statement was that future physical activity initiatives should focus on girls and women because, as a group, girls and women have lower physical activity participation rates than boys and men. The implied causes of this difference were structural factors, such as bias or discrimination against girls and women, with the idea that once these supposed barriers to participation are overcome via public policy, then there will be parity in physical activity participation rates between males and females.

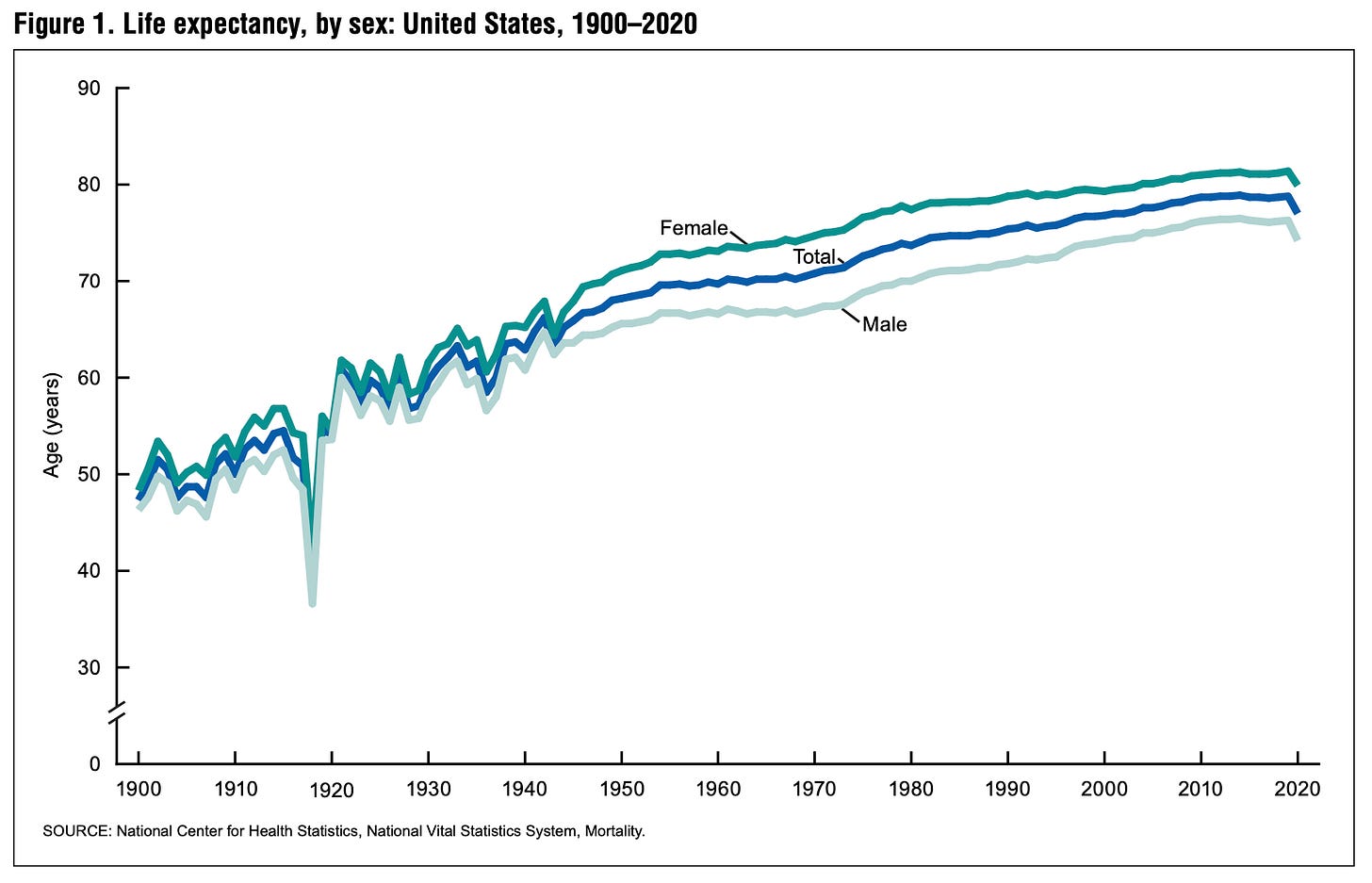

However, if you recall, the authors’ stated purpose for wanting to increase physical activity of select demographic groups, such as girls and women, was to create health equity. This, however, reveals the ACSM’s blind spot and lack of understanding regarding men’s health. A key overall metric of health, which might be used as an outcome for assessing health equity, is life expectancy. Yet, in the United States, life expectancy for males is 5.7 years less than it is for females. Thus, if increased physical activity is indeed effective at improving health, then increasing physical activity of girls and women through targeted policies and initiatives, while simultaneously maintaining the status quo for boys and men, will exacerbate the current 5.7-year life expectancy difference between the sexes.

So, why have I mentioned the ACSM’s equity paper in a post about women as participants in early exercise research? The ACSM’s consensus paper had eight authors. The seventh author listed on the paper is a name that you already know. It is Barbara Ainsworth – the lead author of the 2005 paper that falsely claimed that women were not participants in exercise training studies published in Research Quarterly before 1975.

I hope now you can see that, in many cases, the people who do not understand men’s issues are the same people who do not read history or do not examine history in an objective and accurate manner.

Related Content at The Nuzzo Letter

SUPPORT THE NUZZO LETTER

If you appreciated this content, and the time and effort it took to search the entire archives of Research Quarterly to bring clarity via objective analysis to the topic of women’s participation in early exercise studies, please consider supporting The Nuzzo Letter with a one-time or recurring donation. Your support is greatly appreciated. It helps me to continue to work on independent research projects and fight for more evidence-based discourse. To donate, click the DonorBox logo. In two simple steps, you can donate using ApplePay, PayPal, or another service. Thank you.

Share this post